THE

NEOLITHIC

OF

THE

LEVANT

A.M.T.

Moore

University

College

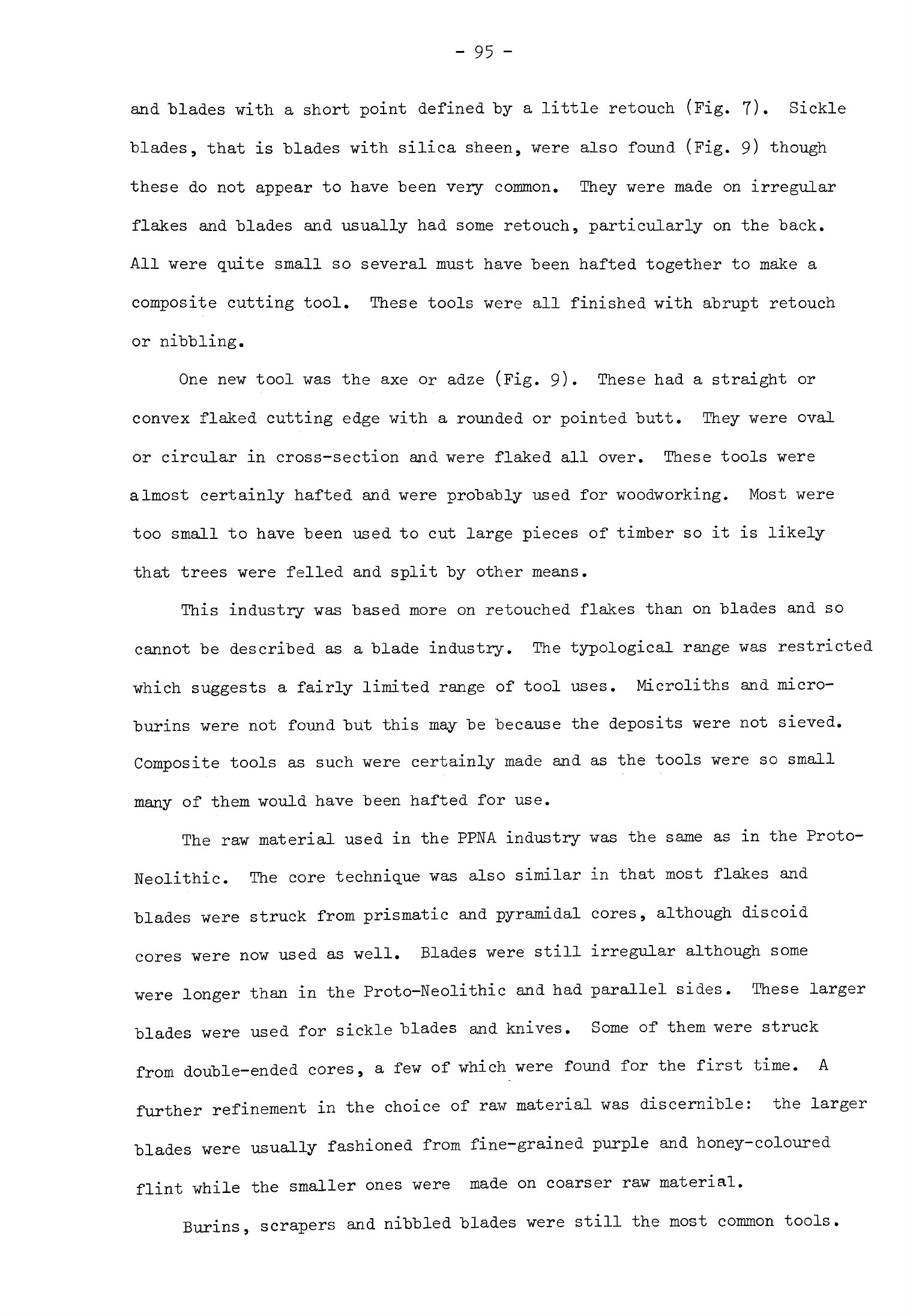

Volume

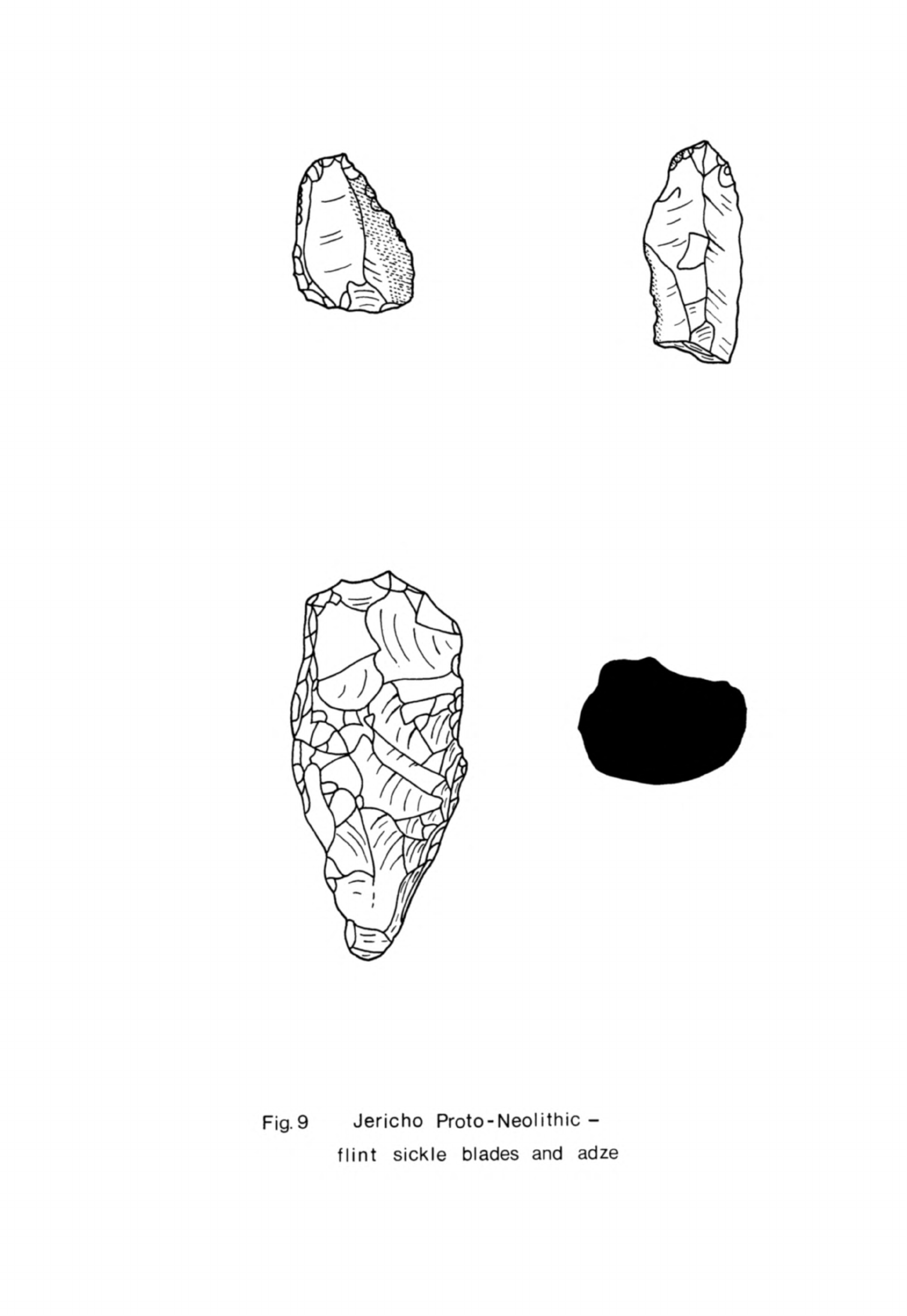

1

Thesis

submitted

for the

Degree

of

Doctor

of

Philosophy,

Oxford

University

1978

-

1

-

CONTENTS

Volume

1

page

CONTENTS

FIGURES

AND

TABLES

ABSTRACT

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

INTRODUCTION

Chapter

1

THE

ENVIRONMENT

OF

THE

LEVANT

IN

THE

LATE

PLEISTOCENE

AND

EARLY

HOLOCENE

Late

Pleistocene

Summary

Early

Holocene

Summary

Chapter

2

THE

MESOLITHIC

OF

THE

LEVANT

Mesolithic

1

Settlement

patterns

Economy

and

society

Mesolithic

2

Settlement

patterns

Economy

and

society

Chapter

3

NEOLITHIC

1

Distribution

of

sites

Economy

Discussion

Chapter

k

NEOLITHIC

2

Middle

Euphrates

West

Syria

Palestine

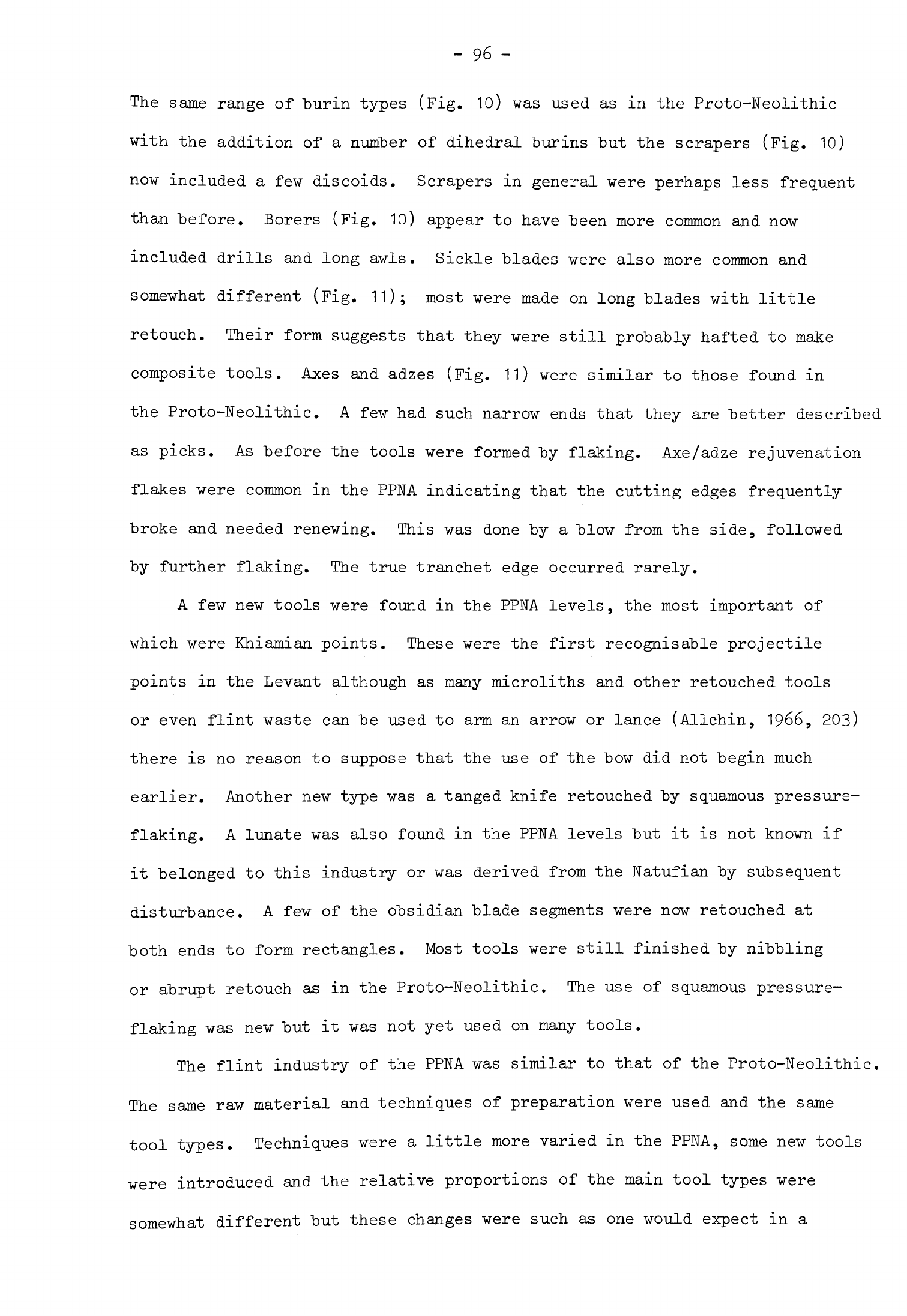

Relationships

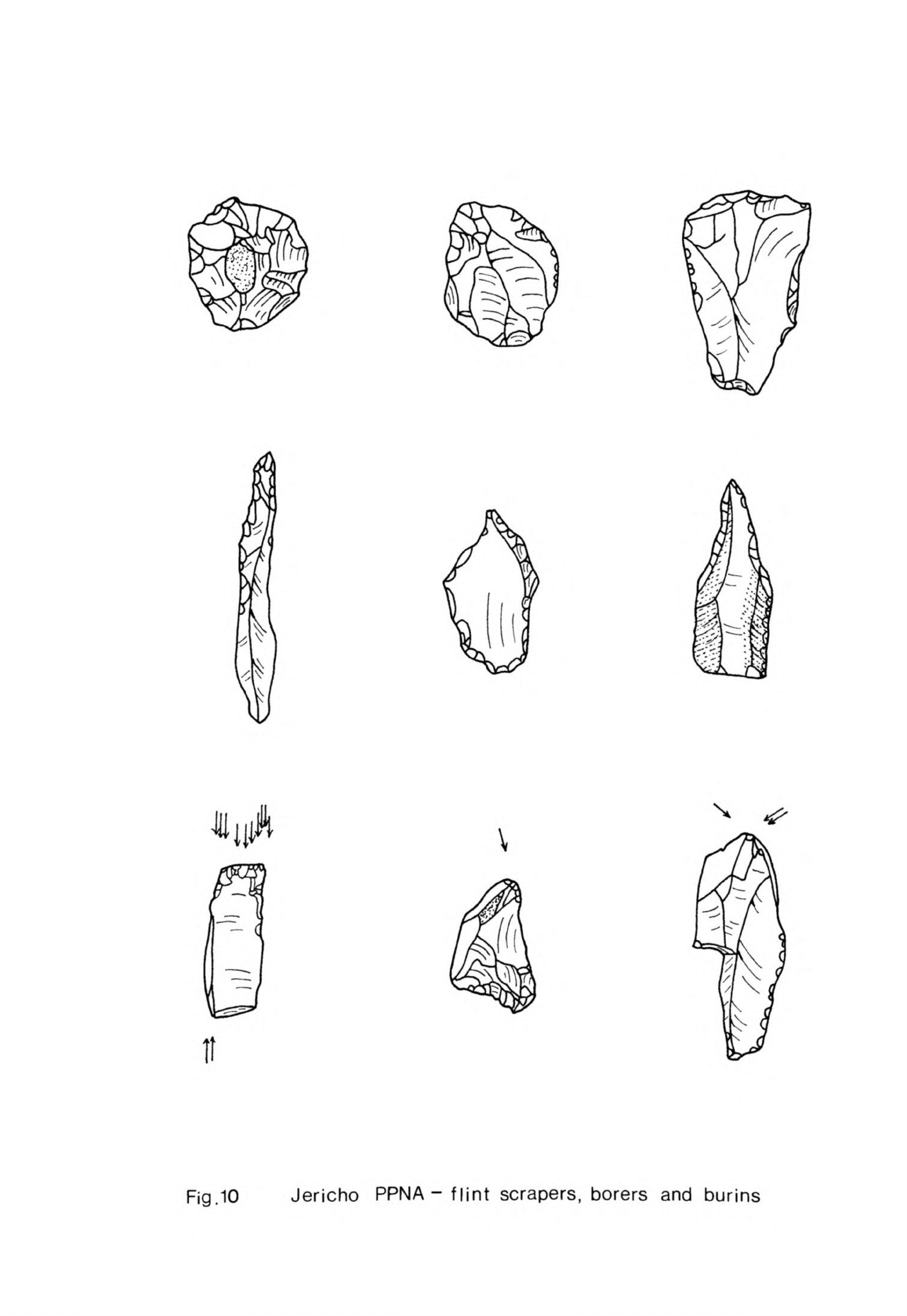

between

Palestinian,

West

Syrian

and

Middle

Euphrates

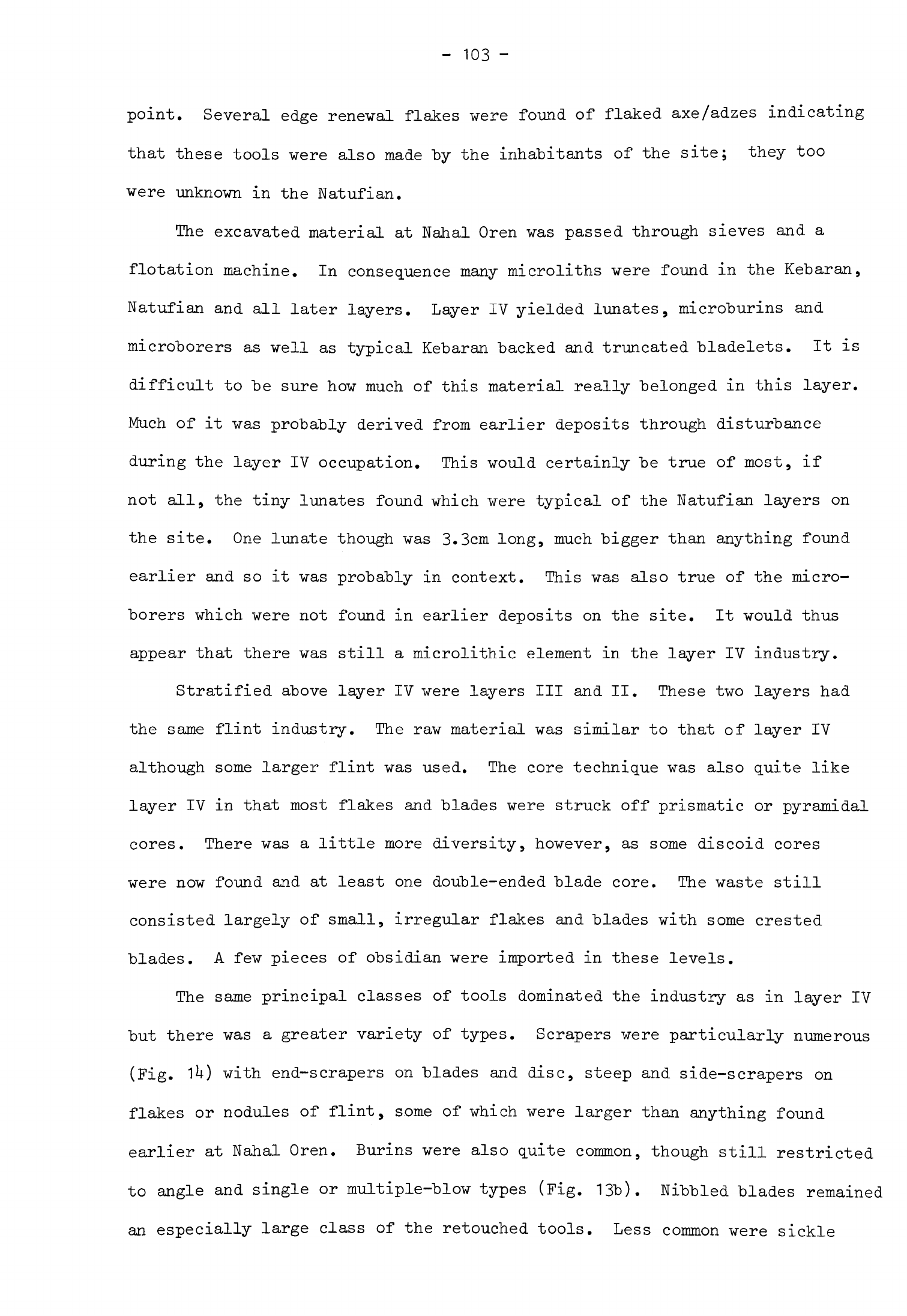

sites

in

Neolithic

2

Mt.

Carmel

Jordan

valley

Judean

hills

Negev

and

Sinai

TransJordan

plateau

IV

vii

viii

1

11

21

25

31

37

hh

^

61

63

Qk

133

136

1U9

160

161

190

211

226

230

231

237

-

11

-

Contents

(continued)

Chapter

k

(continued)

page

Principal

cultural

characteristics

of

Neolithic

2

settlements

Distribution of

sites

Economy

Middle

Euphrates

sites

West

Syrian

sites

Palestinian

sites

Discussion

256

260

265

272

273

286

Volume

2

Chapter

5

NEOLITHIC

3

Middle

Euphrates

North Syria

South

Syria

Lebanese

coast

Beka'a

Damascus

basin

Palestine

South

Palestine

North

Palestine

Principal

cultural

characteristics

of

Neolithic

3

settlements

Timespan

of

Neolithic

3

Distribution

of

sites

Economy

Discussion

Chapter

6

NEOLITHIC

South

Syria

Lebanese

coast

Beka'a

Damascus

basin

Palestine

South

Palestine

North

Palestine

West

Palestine

Distribution

of

sites

296

299

329

3^2

355

358

359

367

379

382

38U

387

397

>*08

UU8

U65

-

Ill

-

Contents

(continued)

page

Chapter

6

(continued)

Economy

Community

organization

and

trade

^-75

Chapter

7

CONCLUSION

^79

APPENDIX

Carbon

1U

dating

^96

NOTES

500

BIBLIOGRAPHY

502

-

iv

-

FIGURES

AND

TABLES

All

artifacts

drawn

full size

unless

otherwise

indicated

page

Volume

1

Fig.

1

The

Levant

1

Fig.

2

A

reconstruction

of

vegetation

zones

c.

9000

B.C.

23

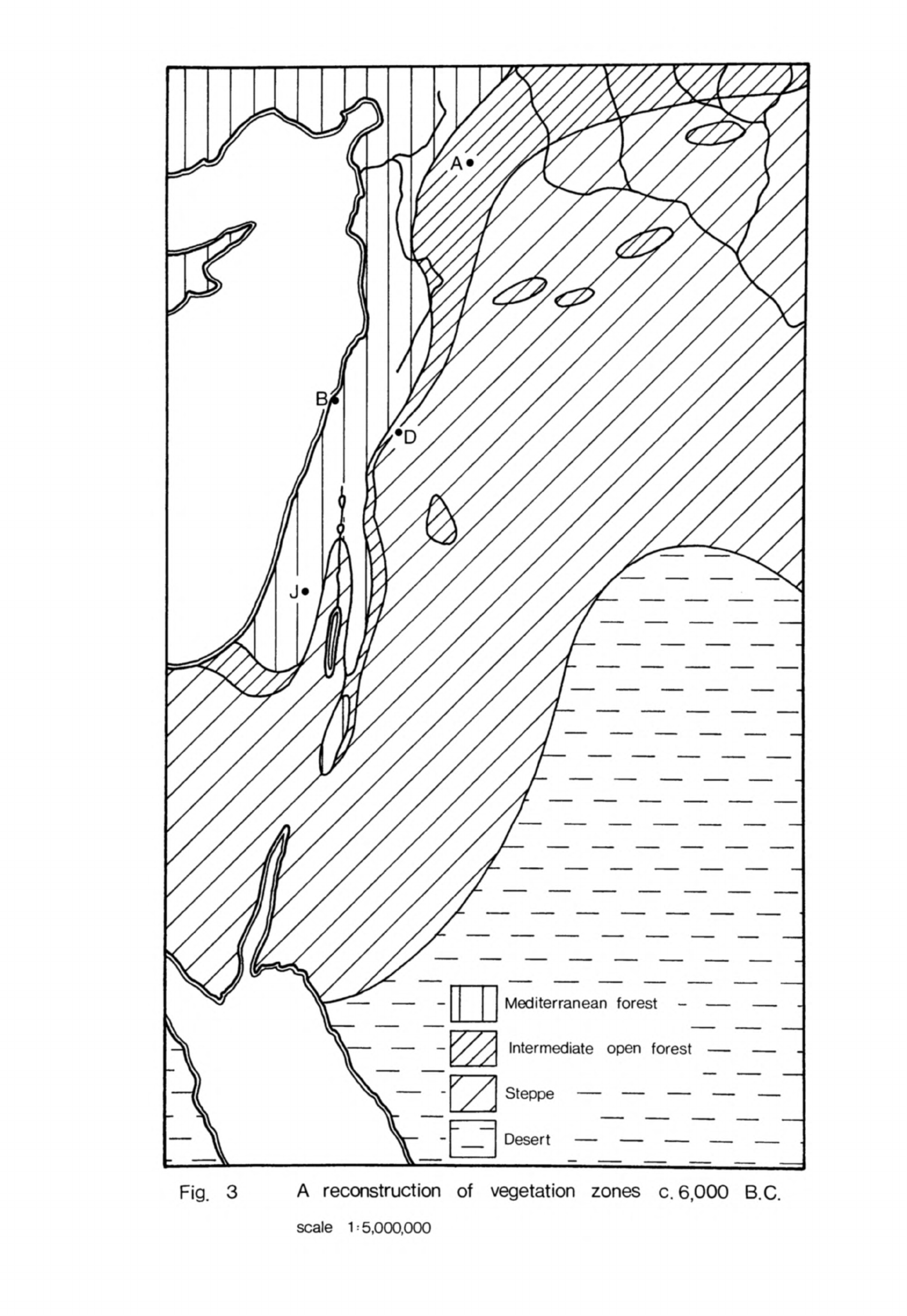

Fig.

3

A

reconstruction

of

vegetation

zones

c.

6000

B.C.

31

Fig.

k

A

reconstruction

of

vegetation

zones

c.

UOOO

B.C.

32

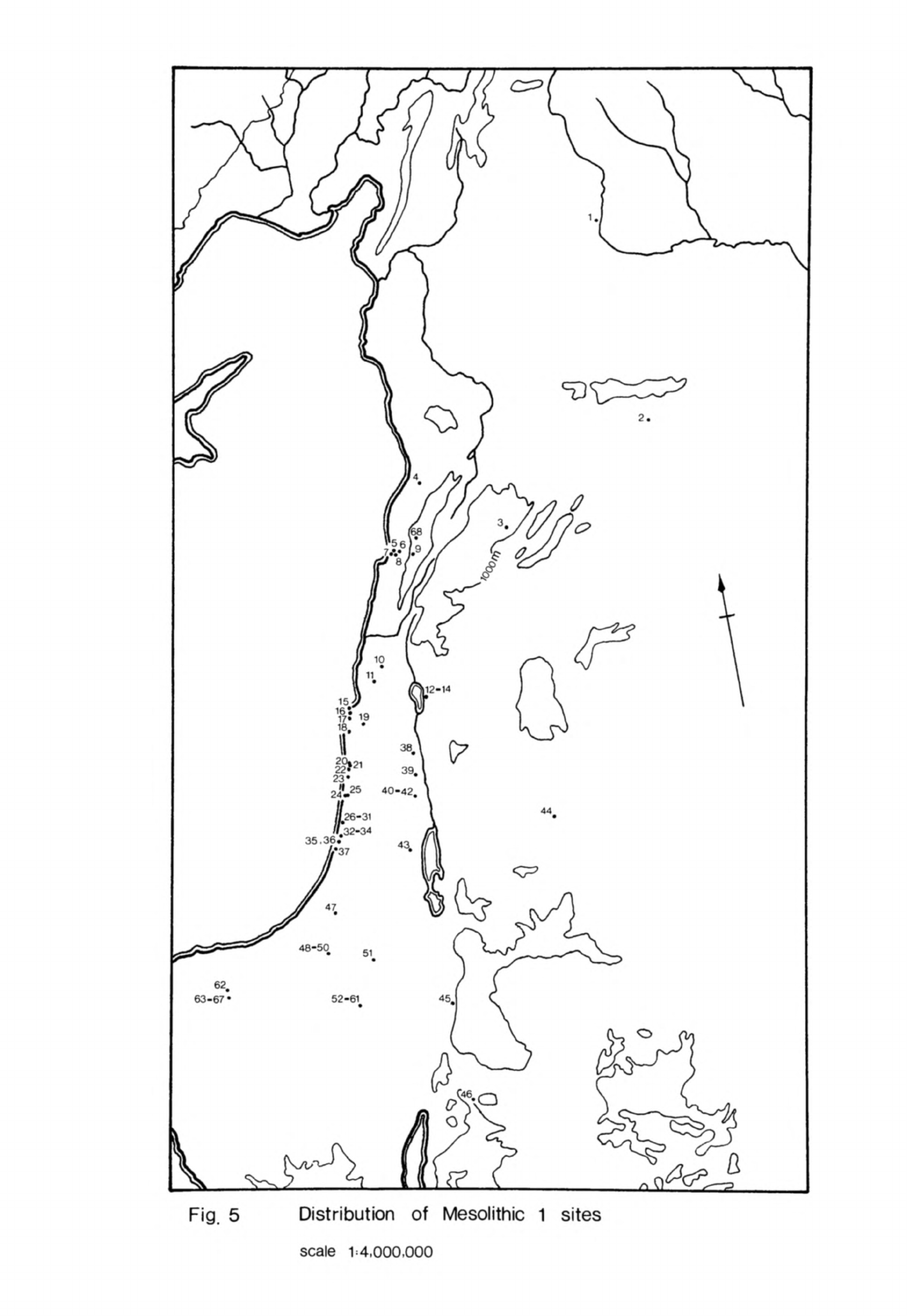

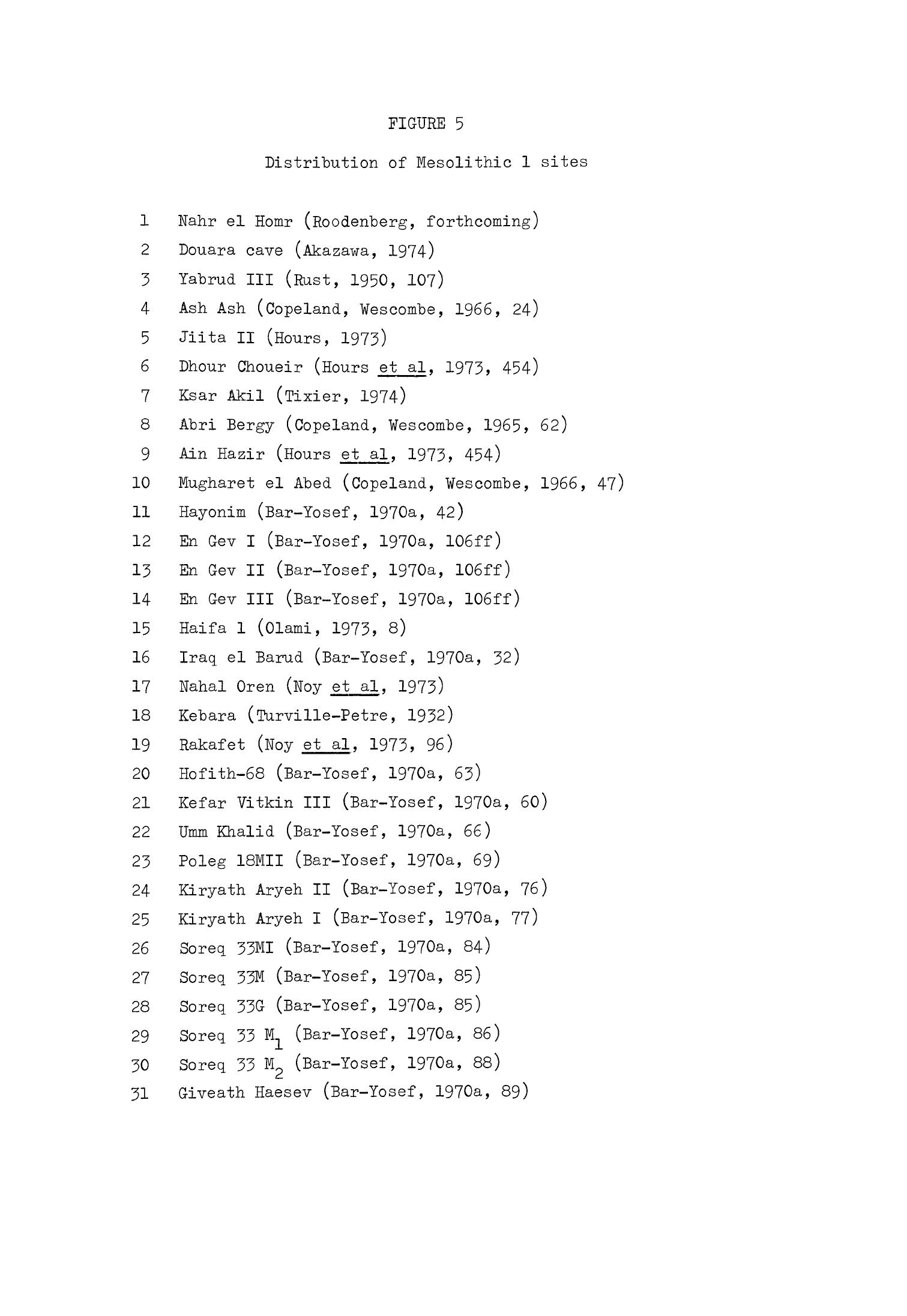

Fig.

5

Distribution

of

Mesolithic

1

sites

^2

Fig.

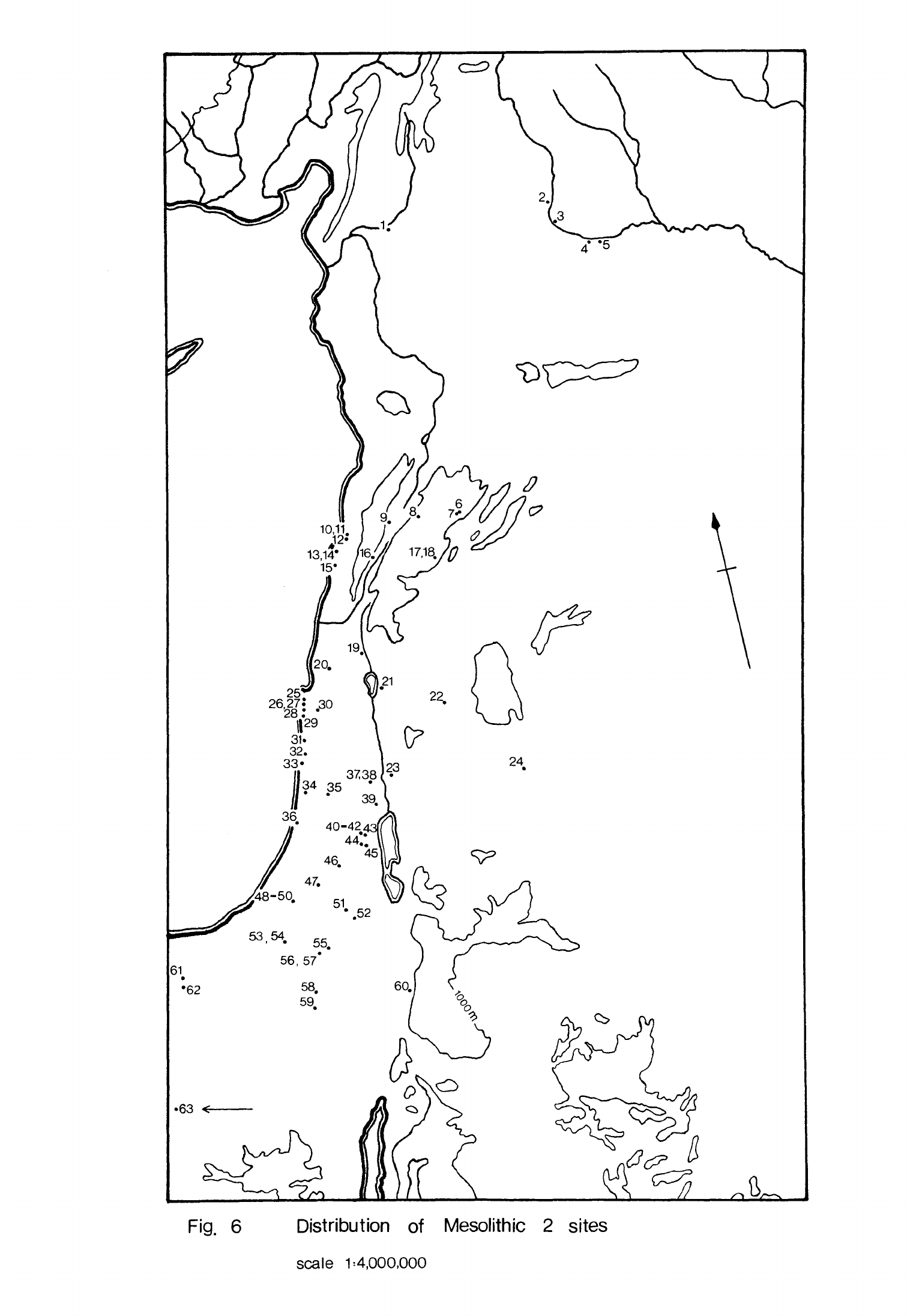

6

Distribution

of

Mesolithic

2

sites

61

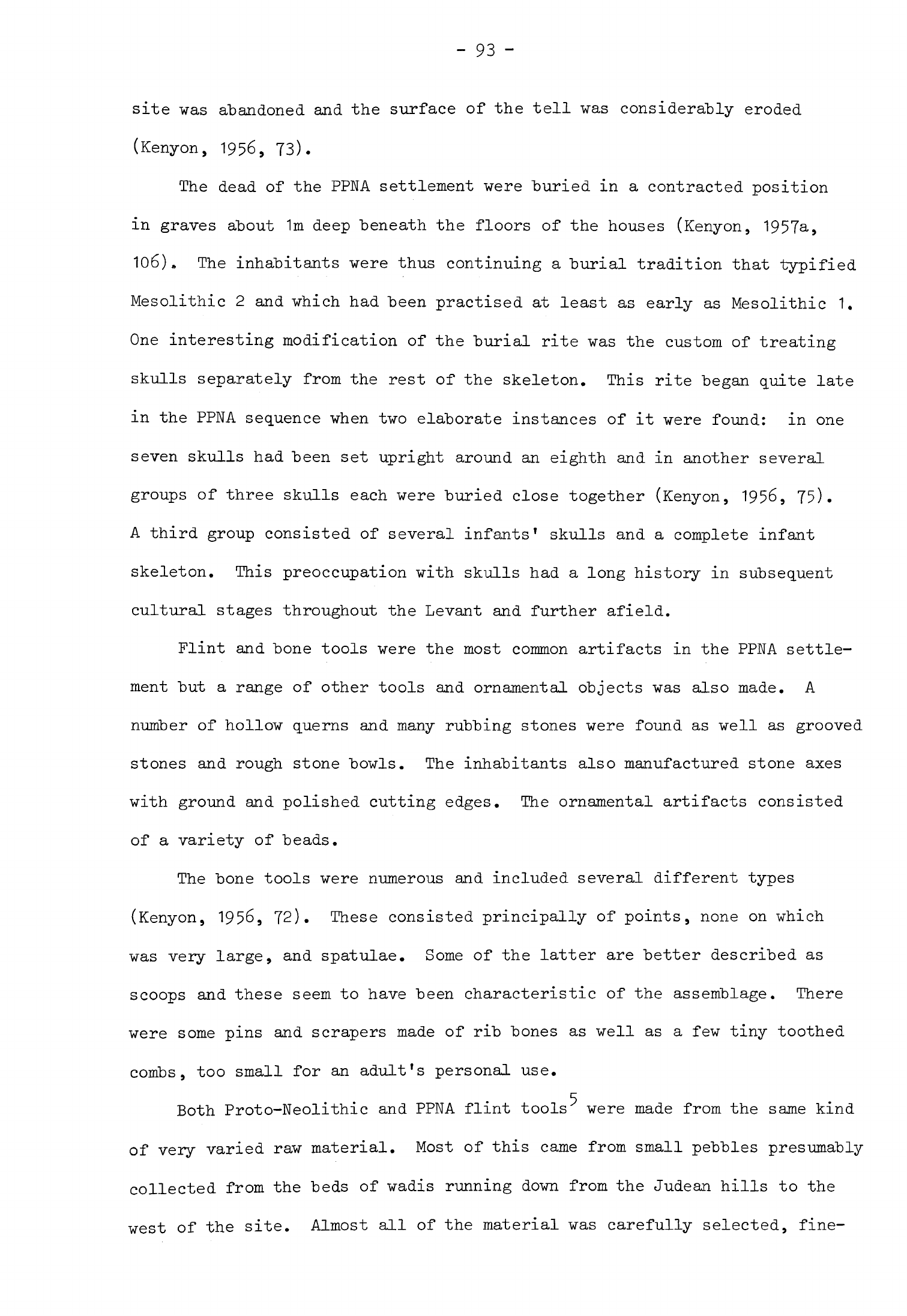

Fig.

7

Jericho

Proto-Neolithic

-

flint

borers and burins

93

Fig.

8

Jericho

Proto-Neolithic

-

flint

scrapers

9^-

Fig.

9

Jericho

Proto-Neolithic

-

flint

sickle

blades

and

adze

95

Fig.

10

Jericho

PPNA

-

flint

scrapers,

borers

and

burins

96

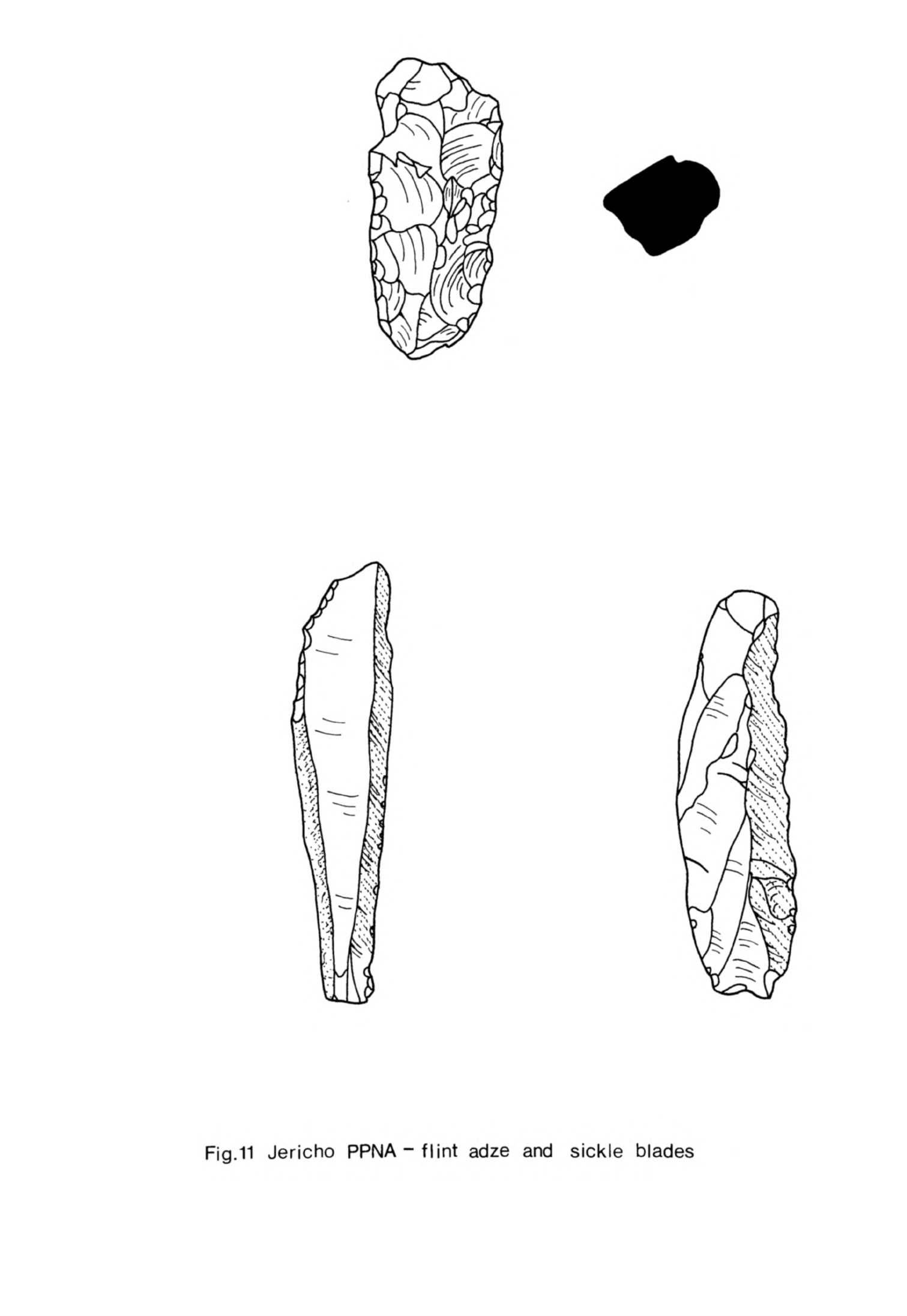

Fig.

11

Jericho

PPNA

-

flint

adze

and

sickle

blades

96

Fig.

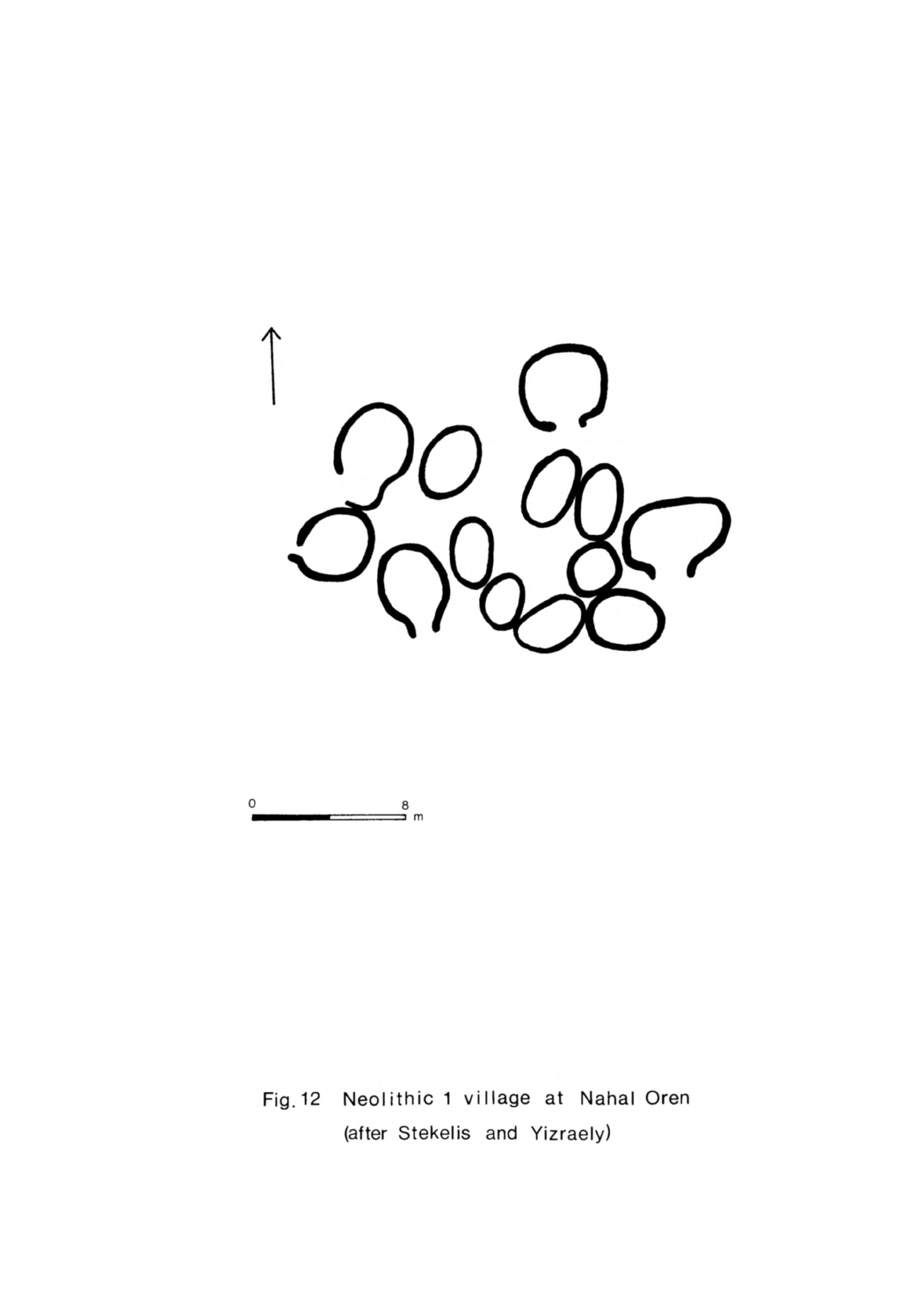

12

Neolithic

1

village

at

Nahal

Oren

(after

Stekelis

and

Yizraely)

100

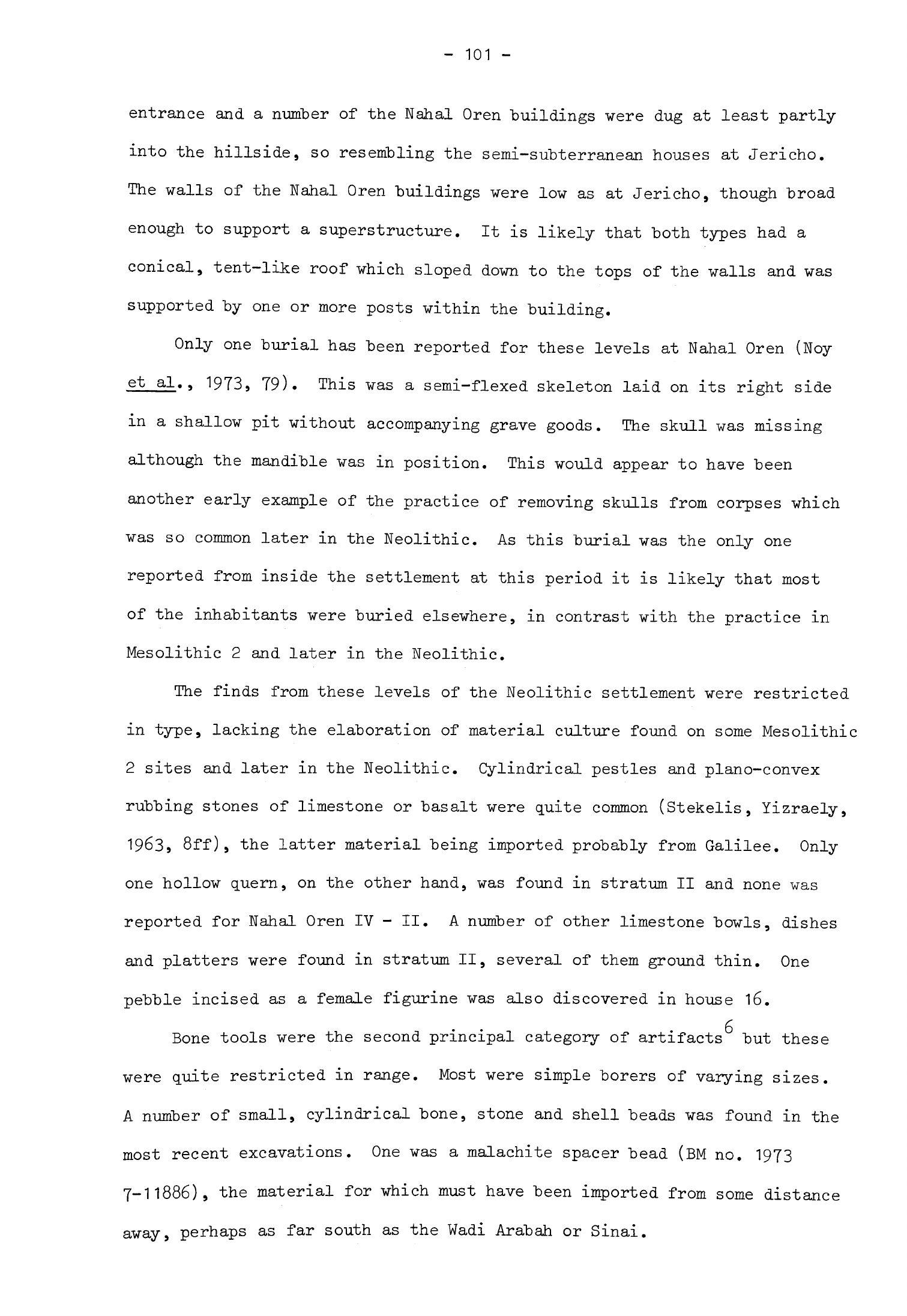

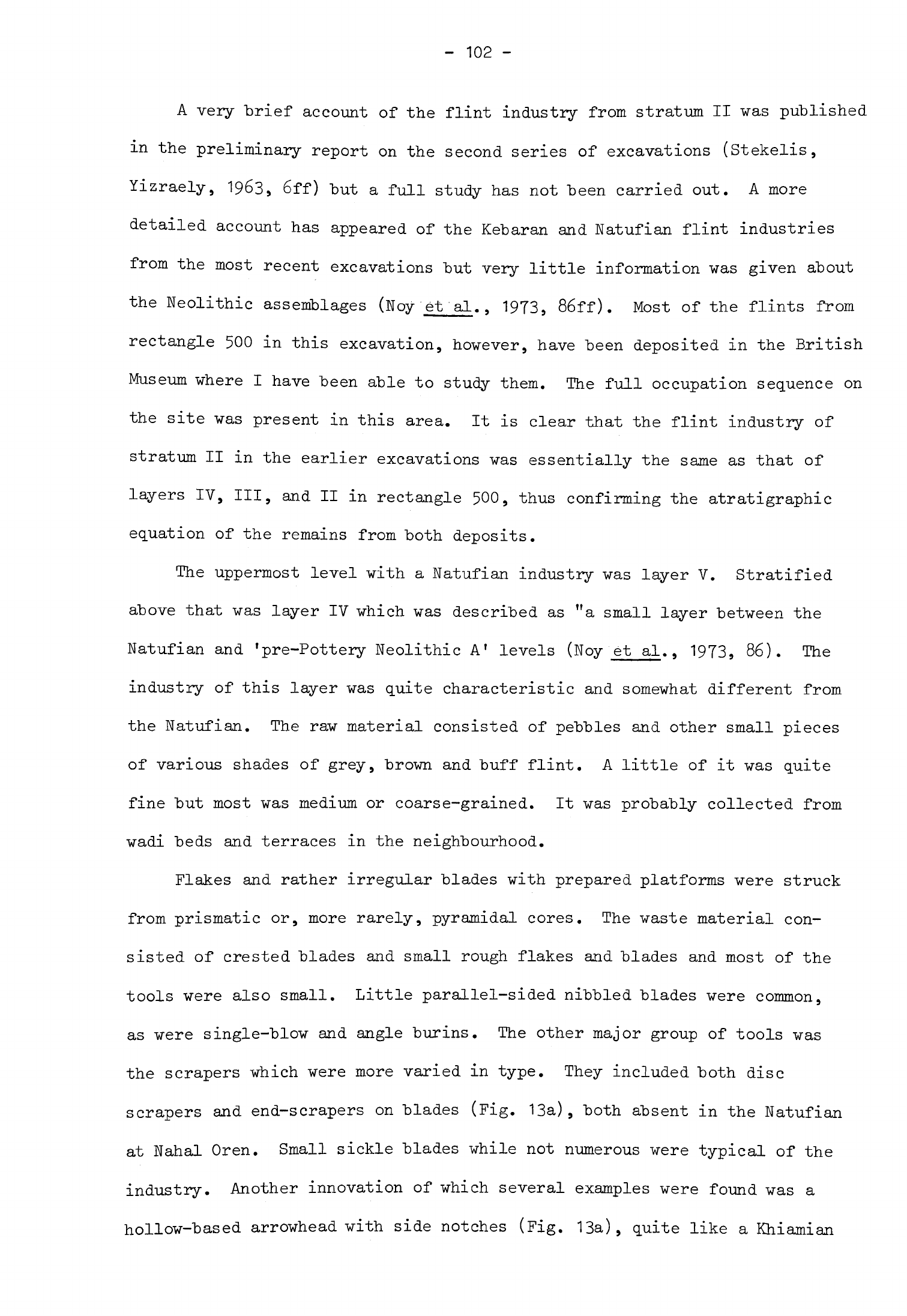

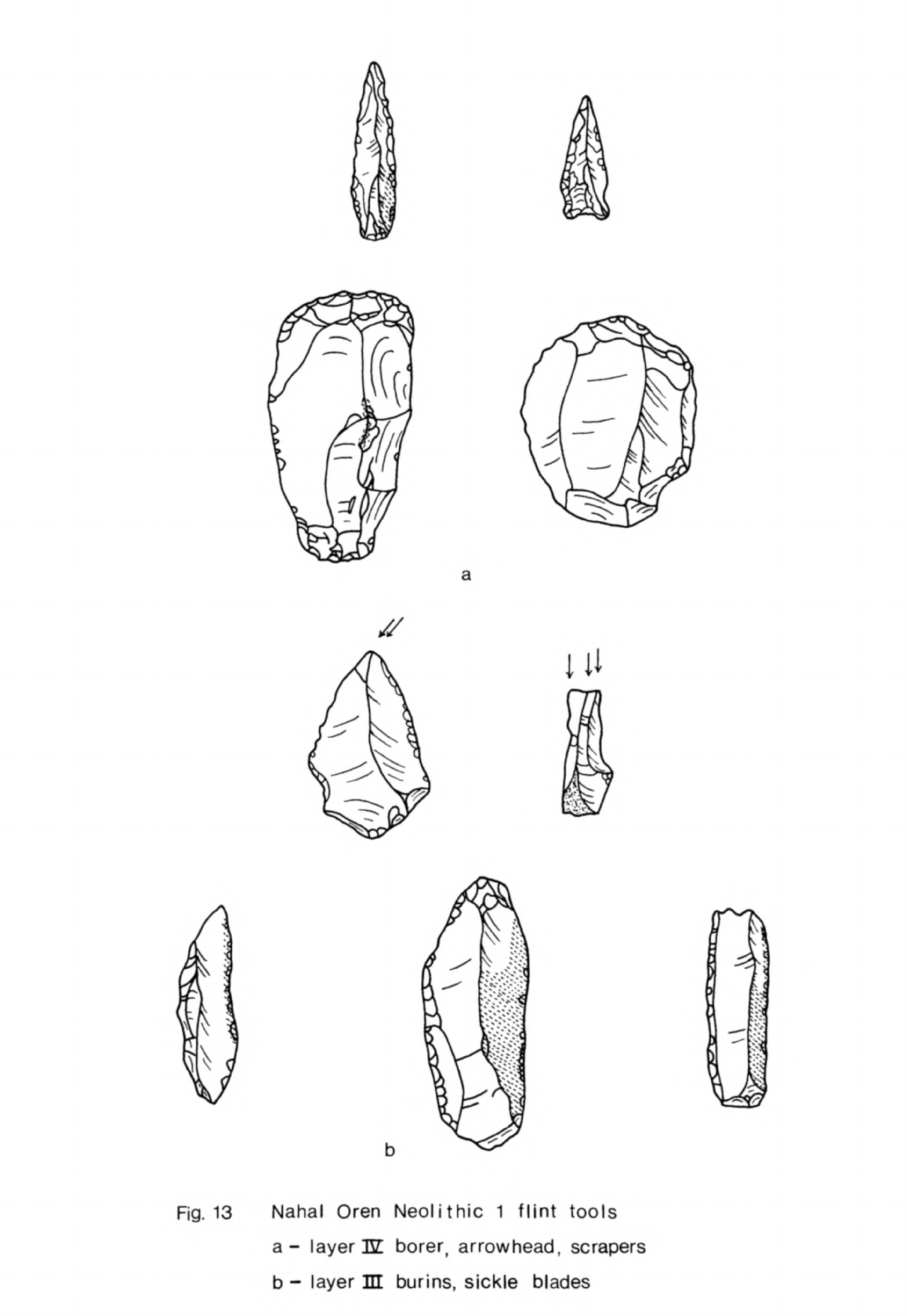

Fig.

13

Nahal

Oren

Neolithic

1

flint

tools

102

Fig.

1U

Nahal

Oren

Neolithic

1

flint

tools

103

Fig.

15

a

-

El

Khiam

points (after

Perrot)

107

b

-

Harif

points

(after

Marks)

Fig.

16

Mureybat

IB-Ill

-

flint

arrovheads

and

adze

(after

Cauvin)

121

Fig.

17

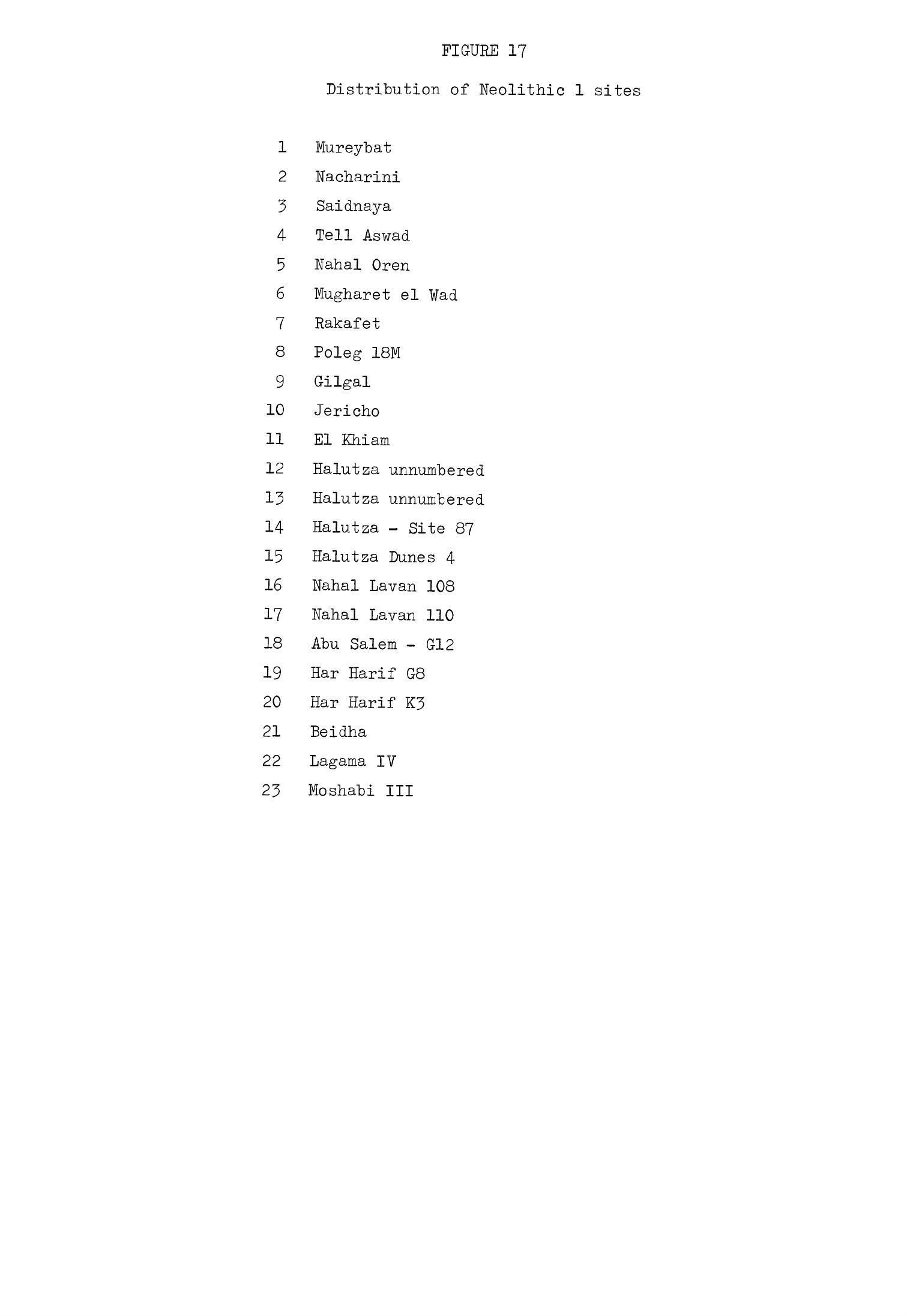

Distribution

of

Neolithic

1

sites

133

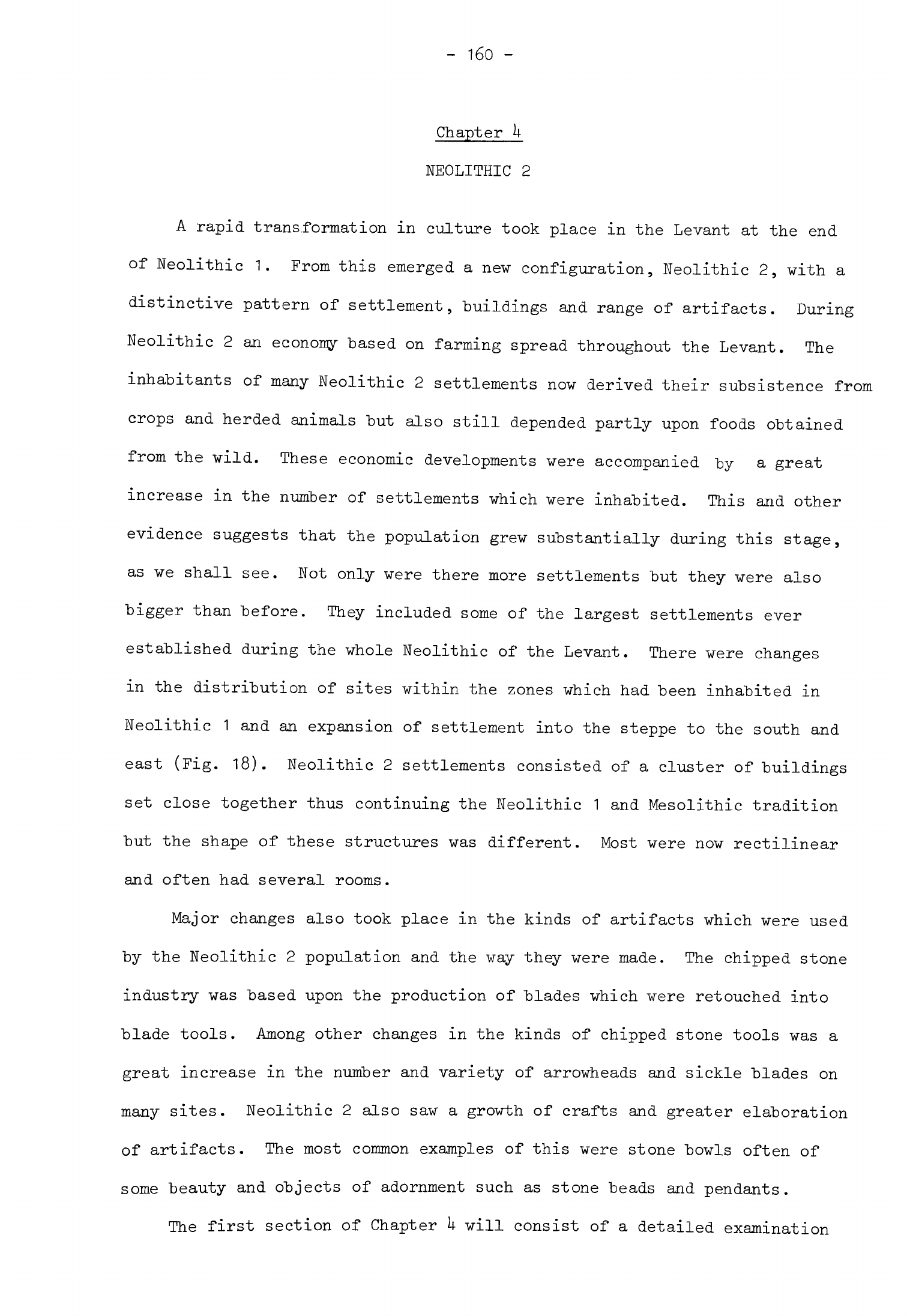

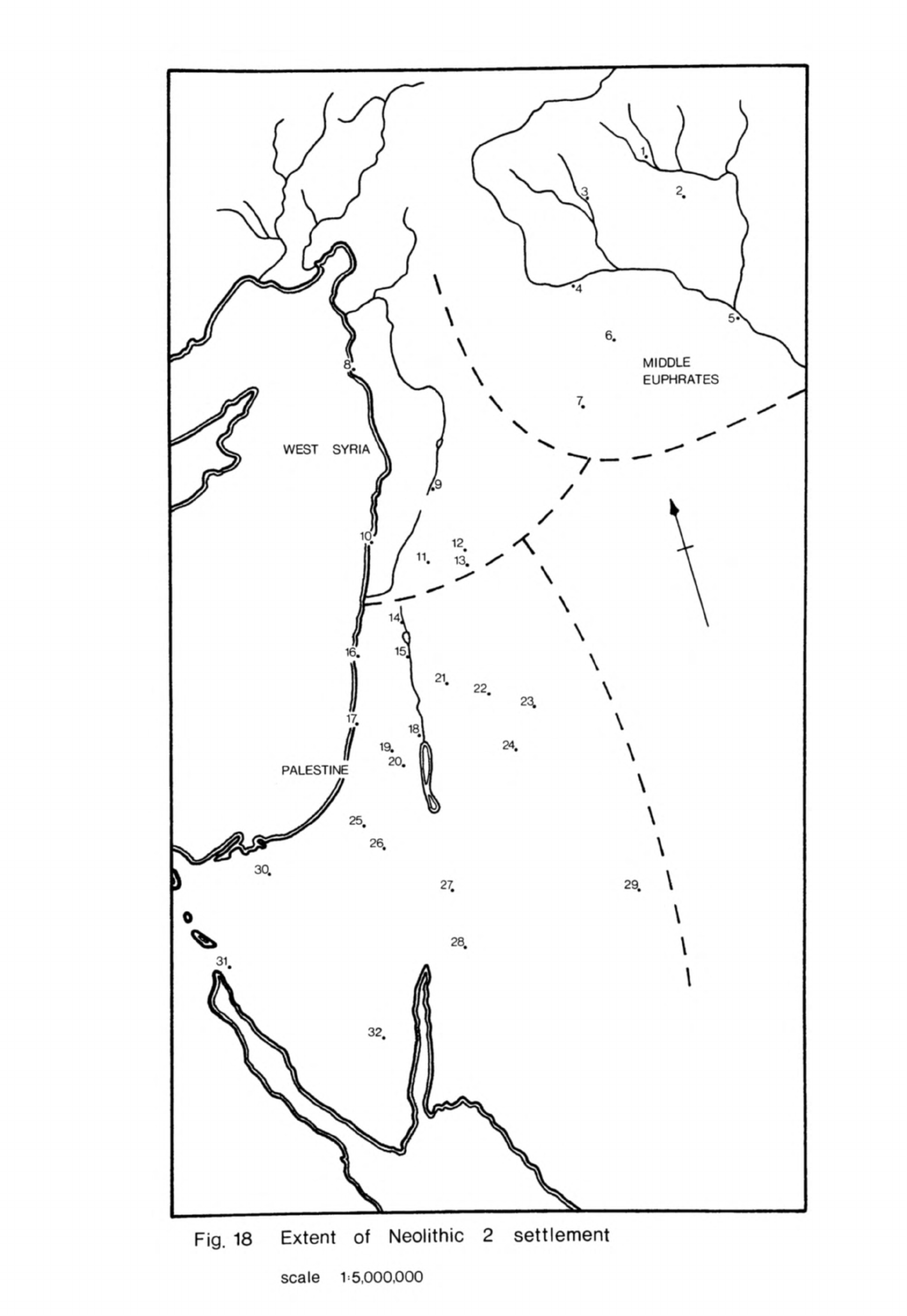

Fig.

18

Extent

of

Neolithic

2

settlement

160

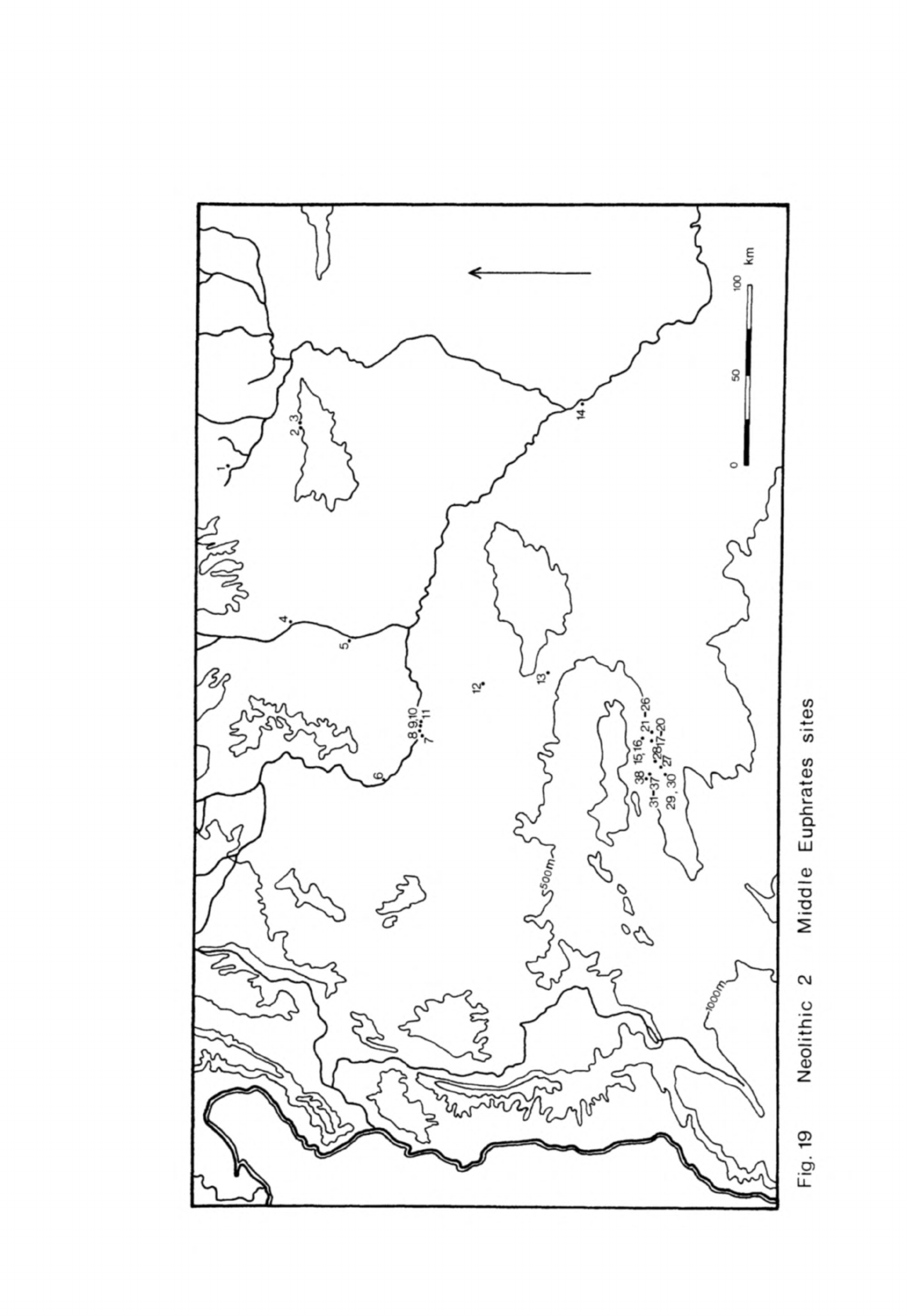

Fig.

19

Neolithic

2

Middle

Euphrates

sites

161

Fig.

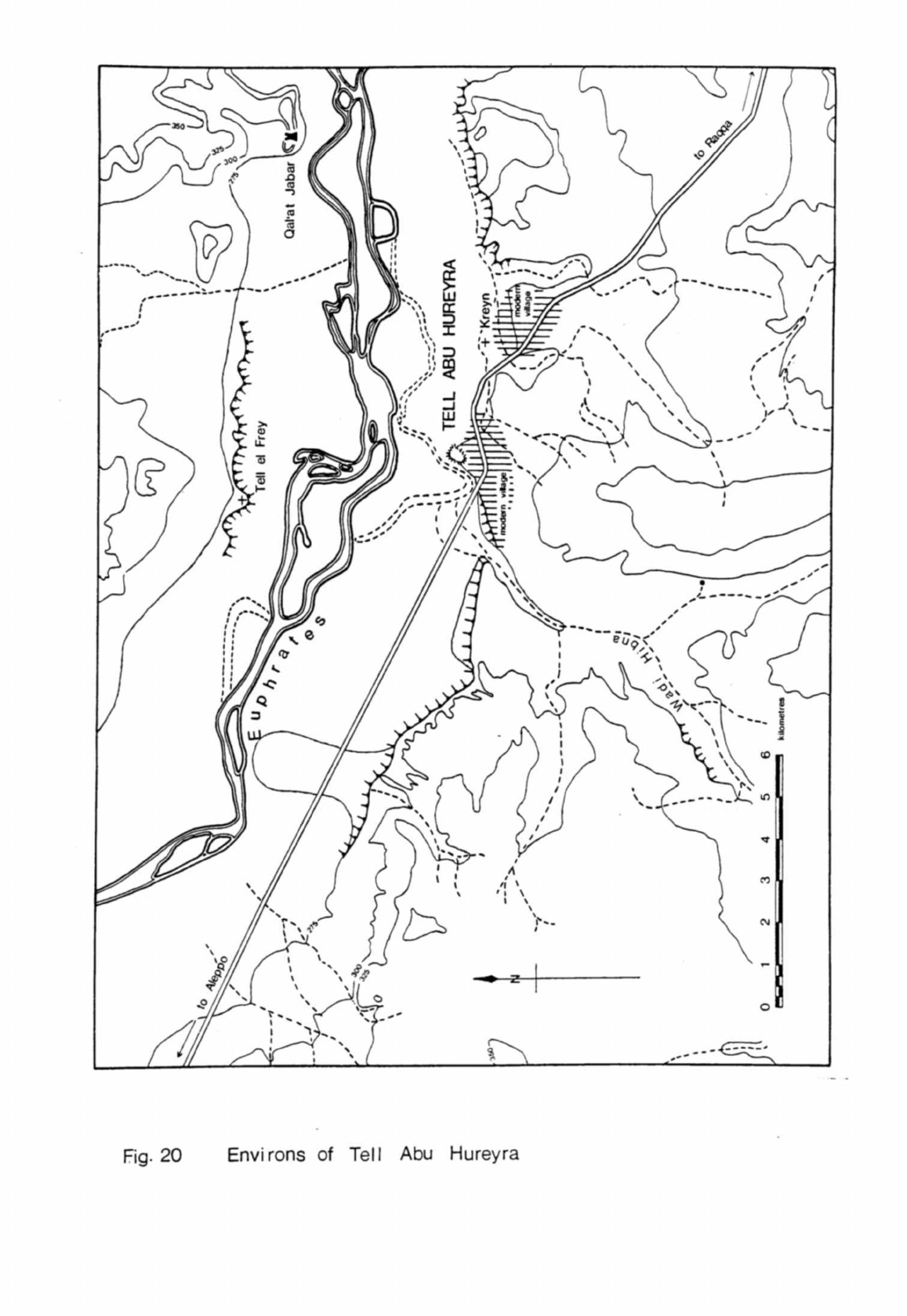

20

Environs

of

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

163

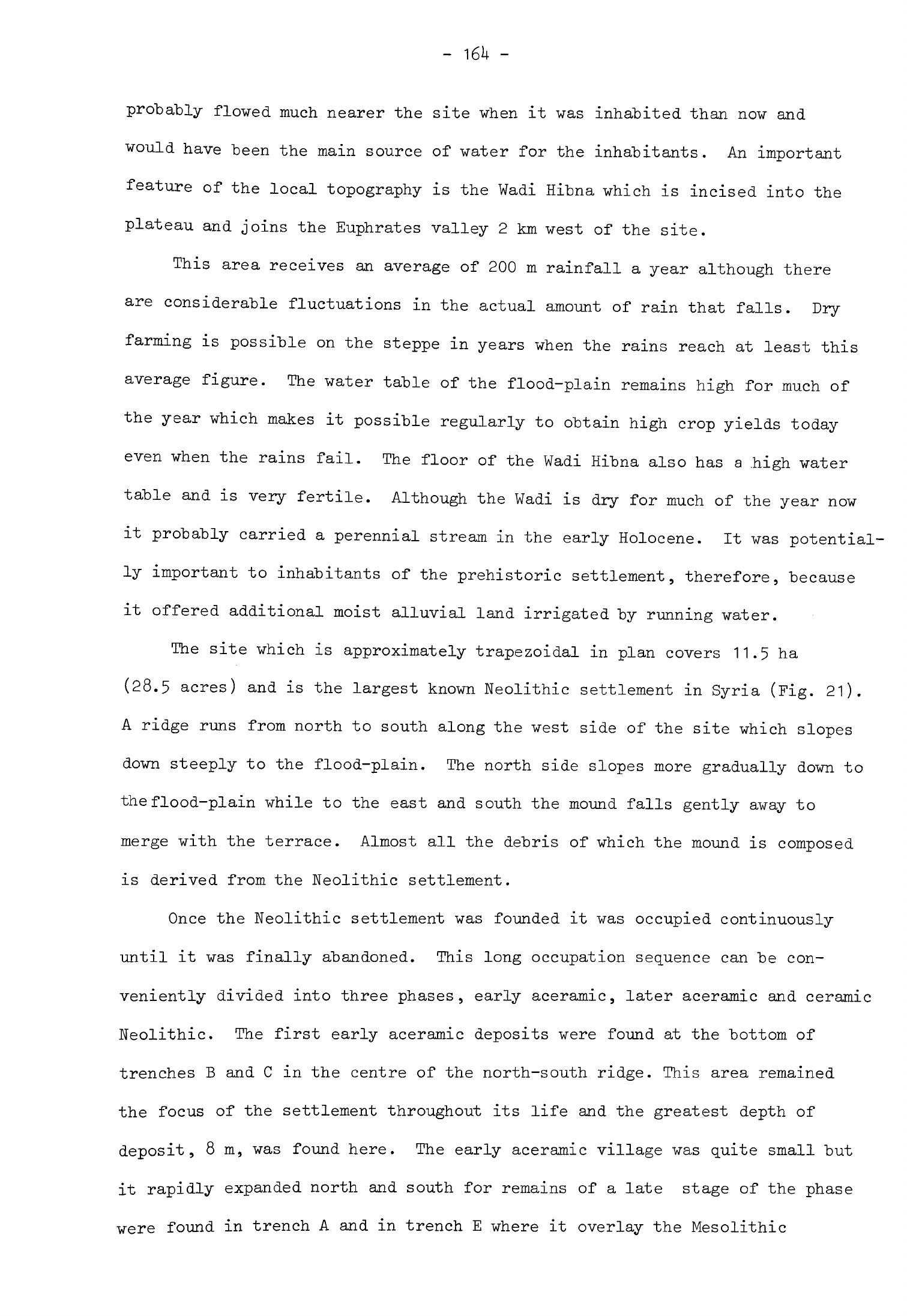

Fig.

21

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

contour

plan

16U

Fig.

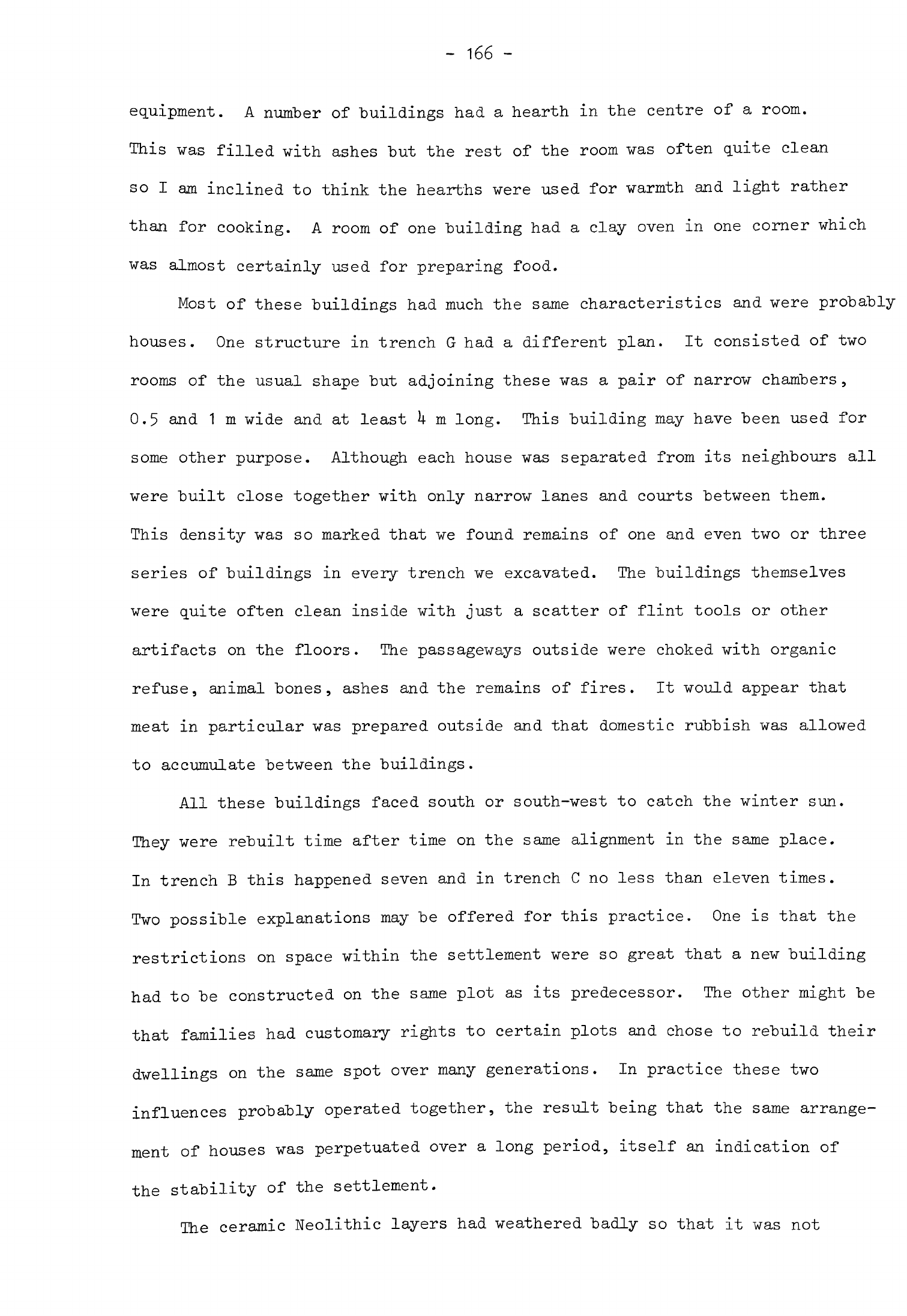

22

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

butterfly

beads

166

Fig.

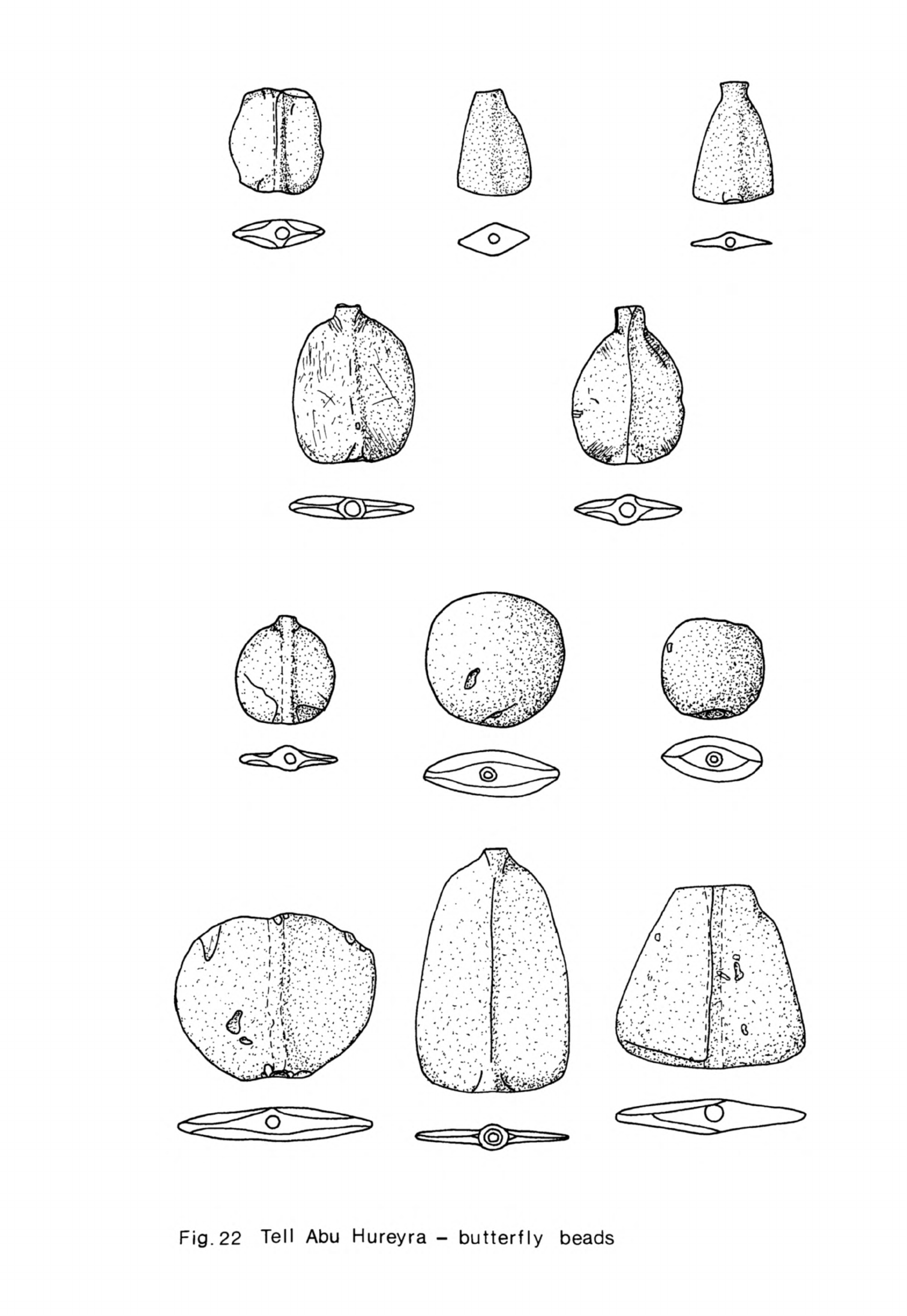

23 Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

double-ended

flint

cores

167

Fig.

2U

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

flint

arrowheads

168

-

v

-

Figures

and

Tables

(continued)

page

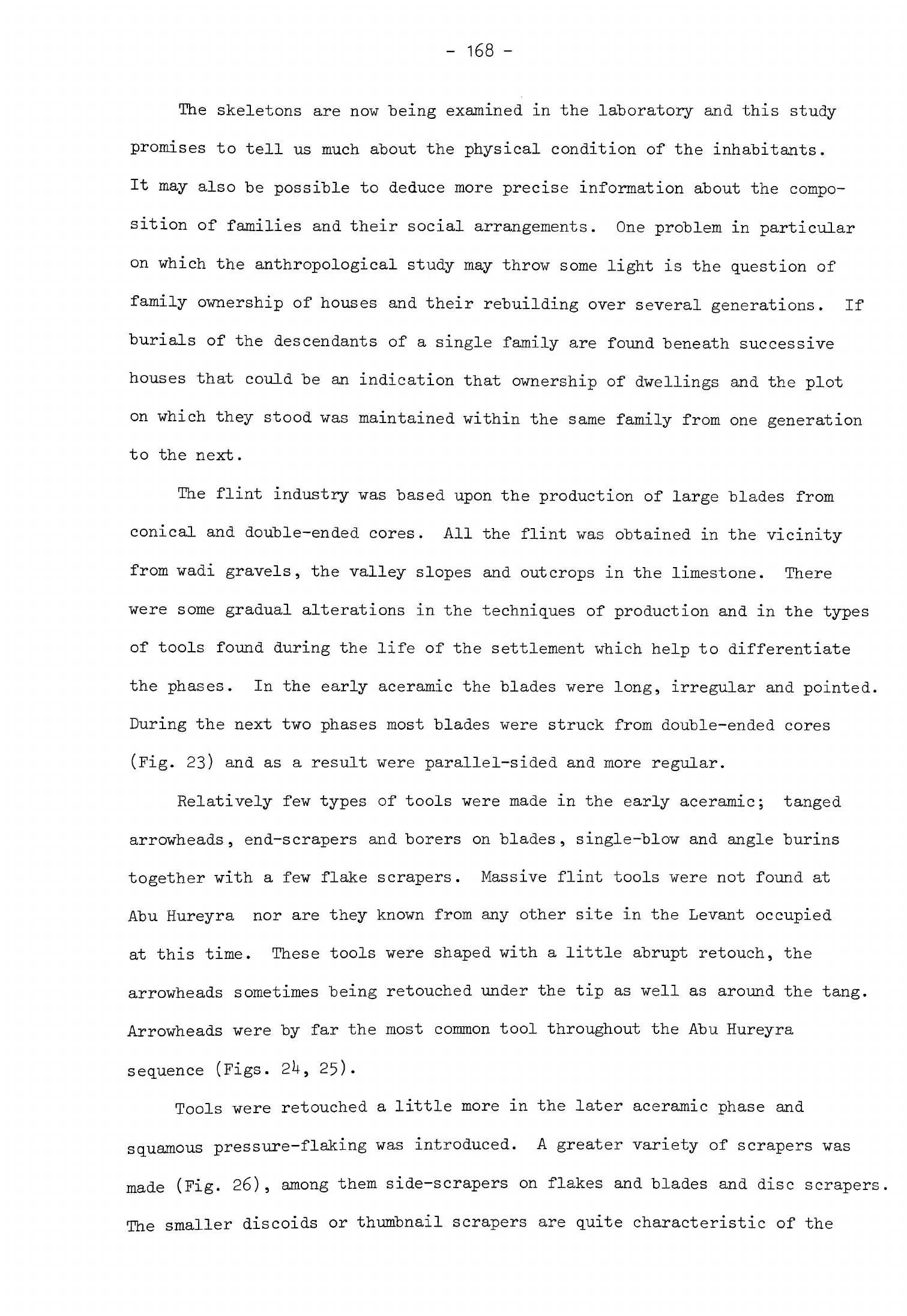

Fig.

25

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

Amuq

arrowheads

168

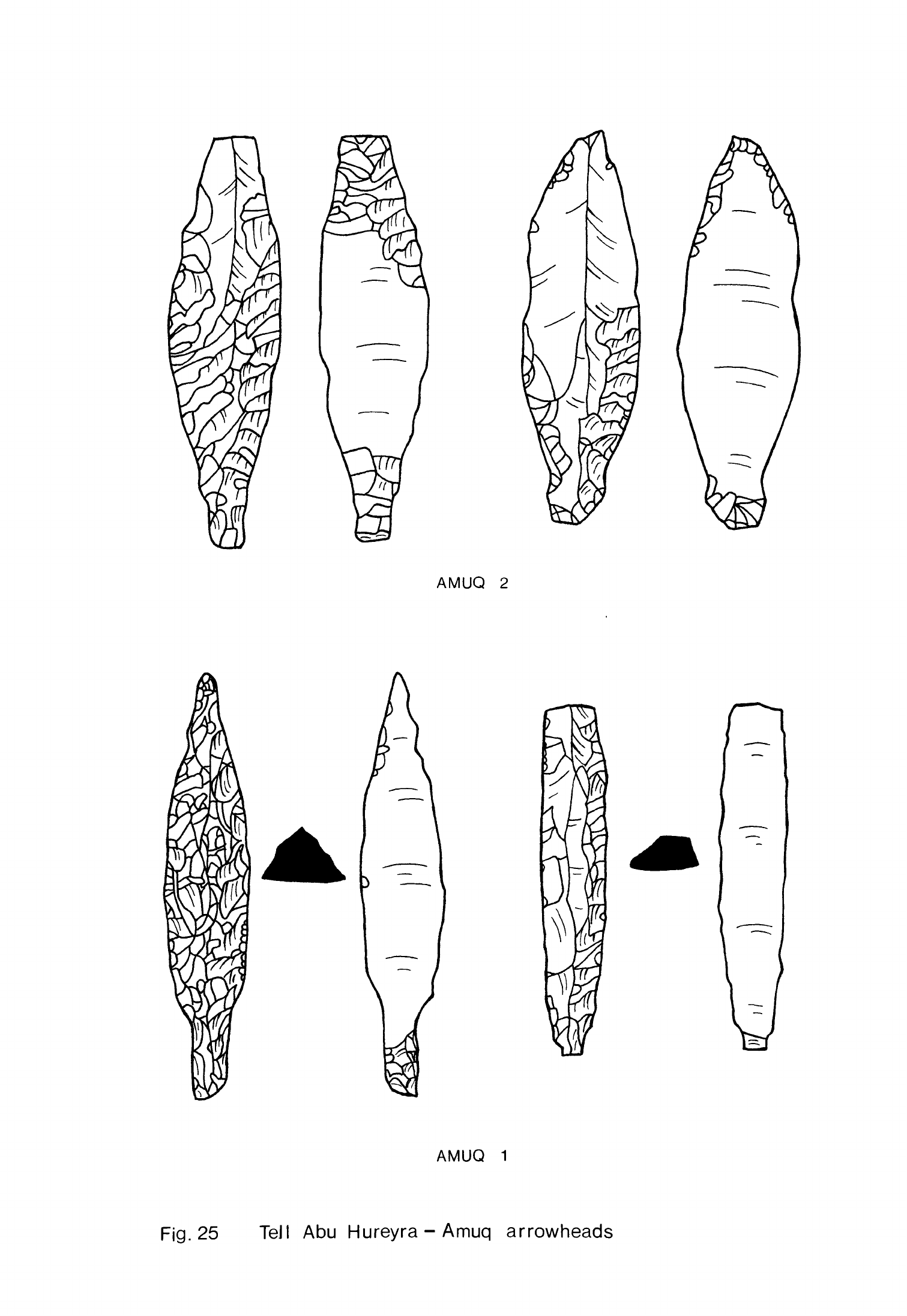

Fig.

26

Tell

Abu Hureyra

-

flint

scrapers

168

Fig.

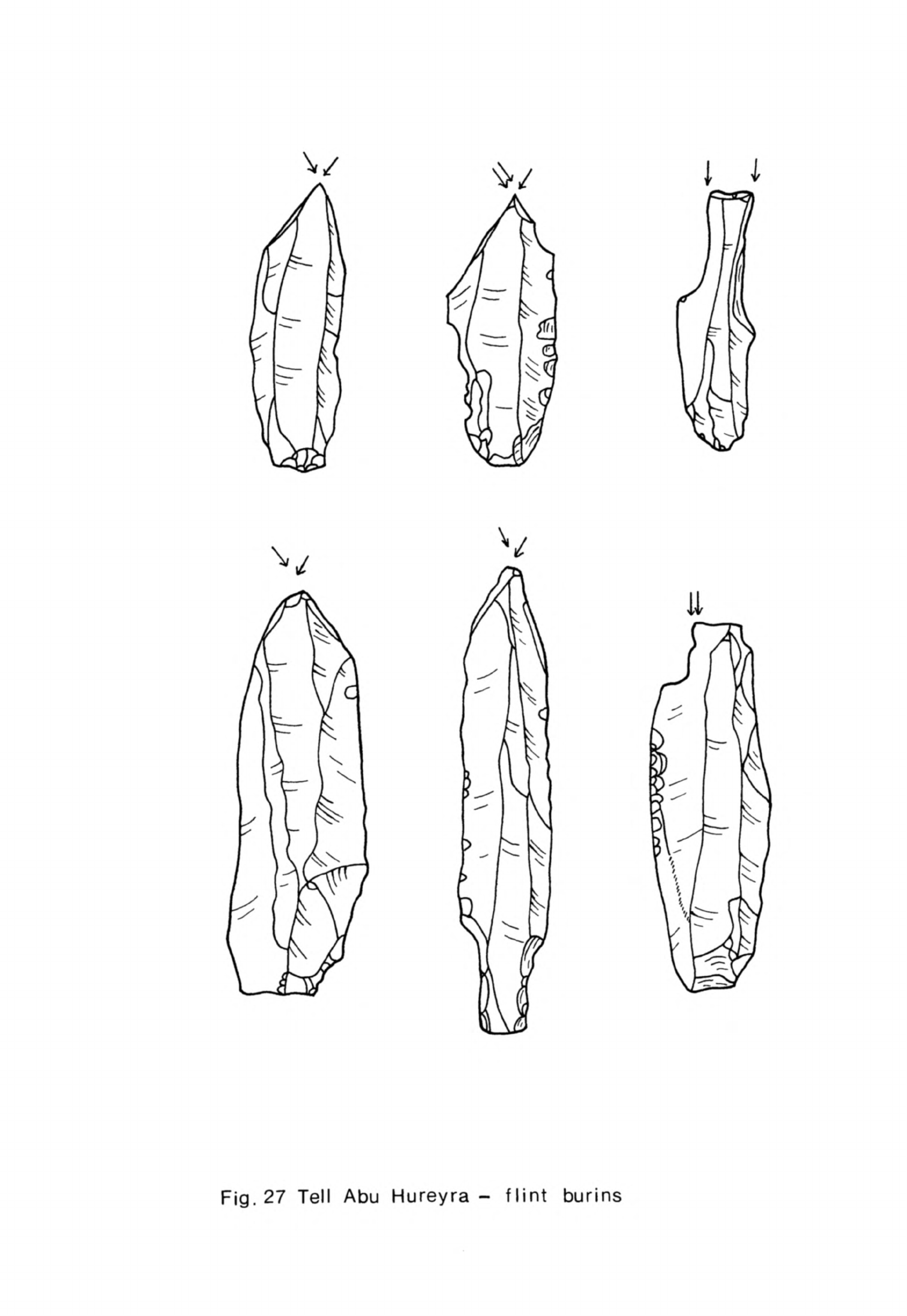

27

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

flint

burins

169

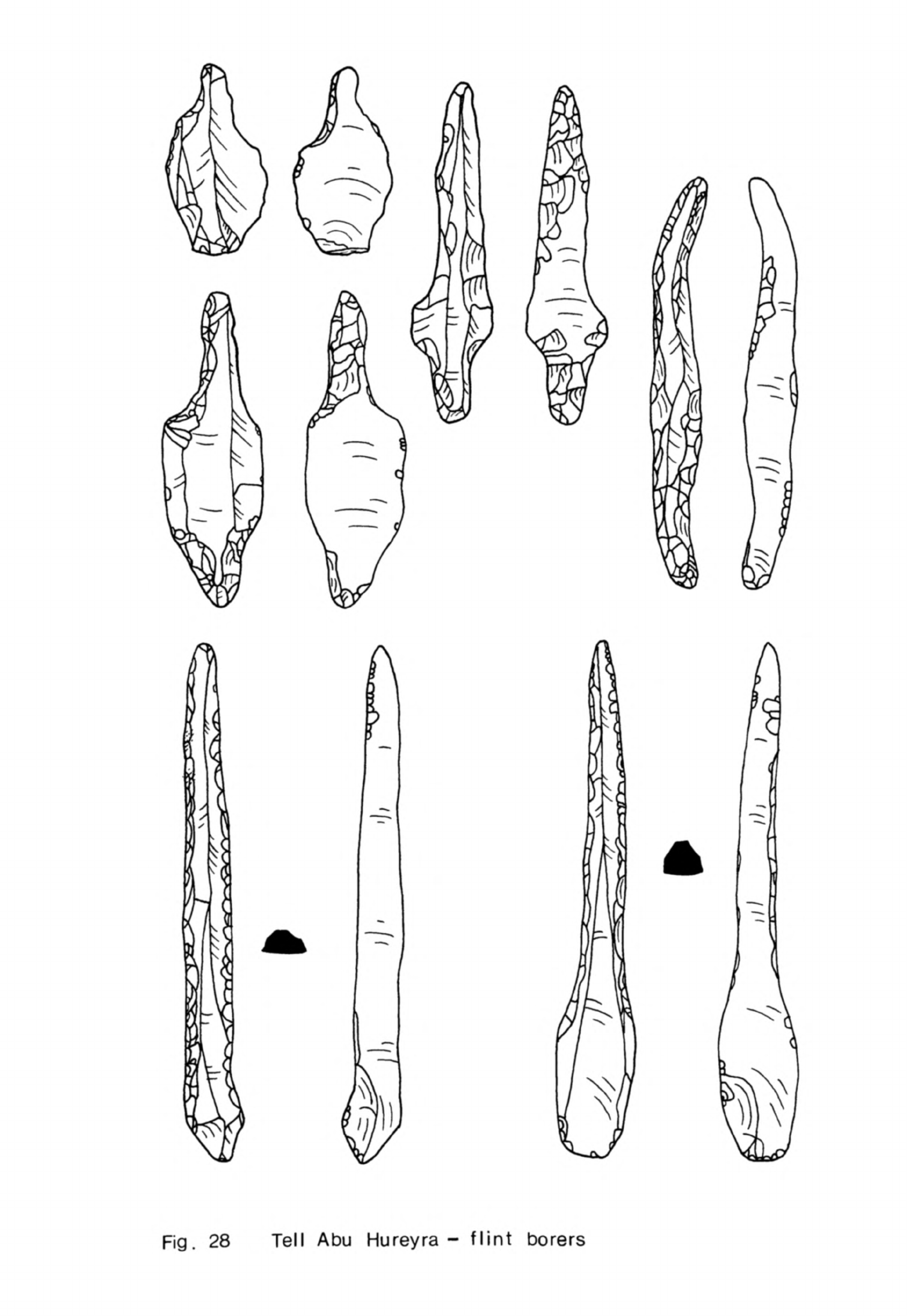

Fig.

28

Tell

Abu Hureyra

-

flint

borers

169

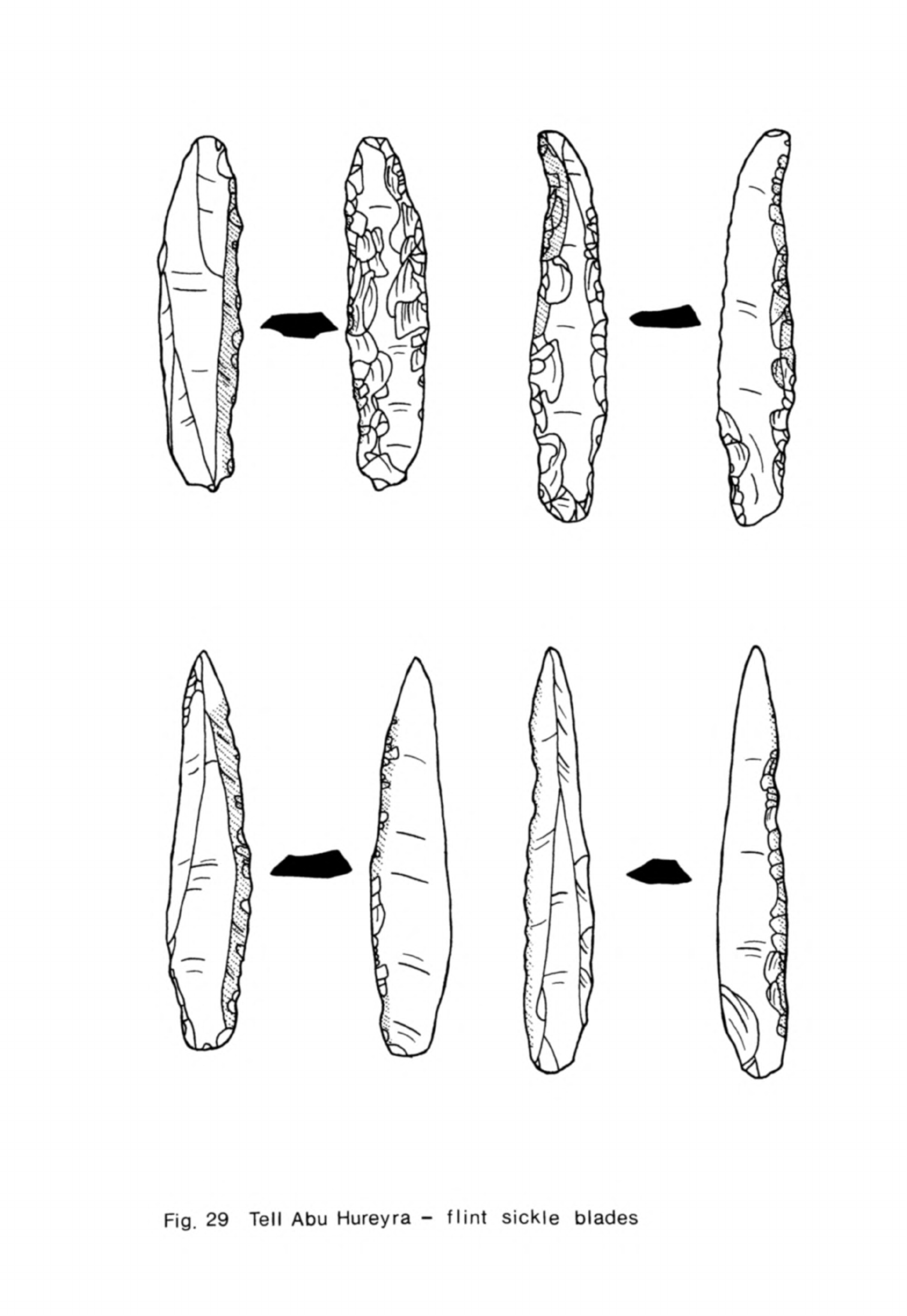

Fig.

29

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

flint

sickle

blades

169

Fig.

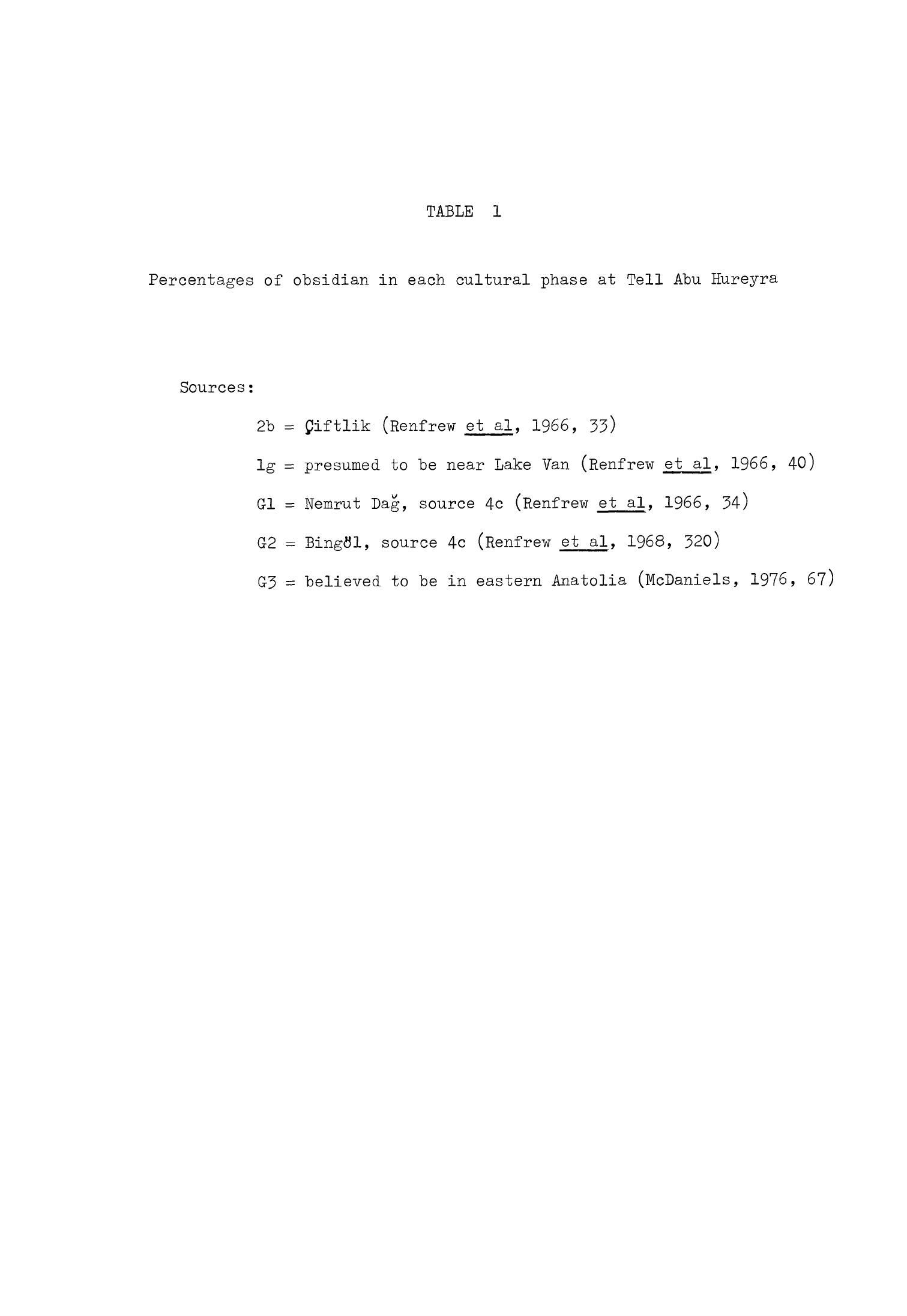

30

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

bone

tools

171

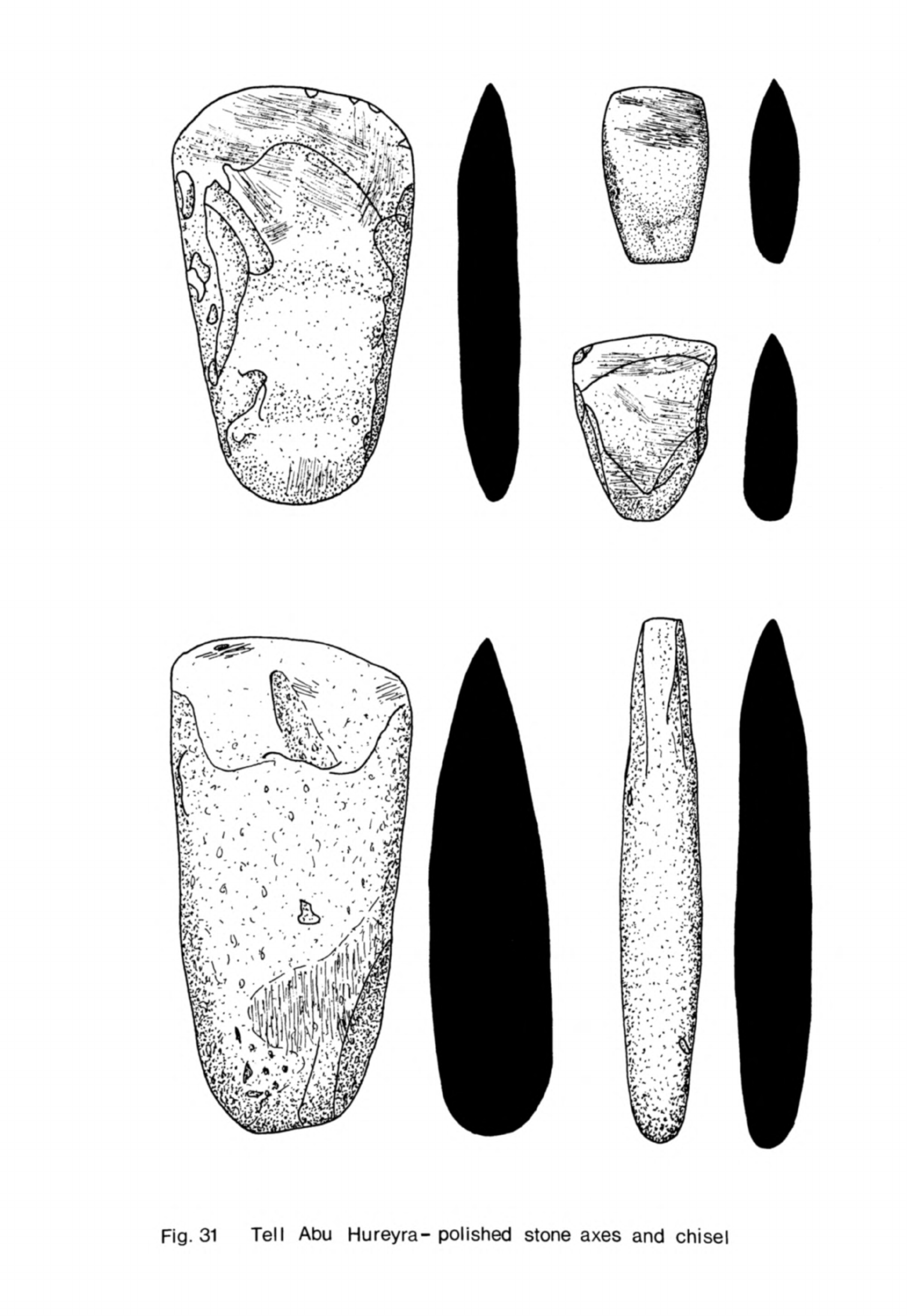

Fig.

31

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

-

polished

stone

axes

and

chisel

172

Fig.

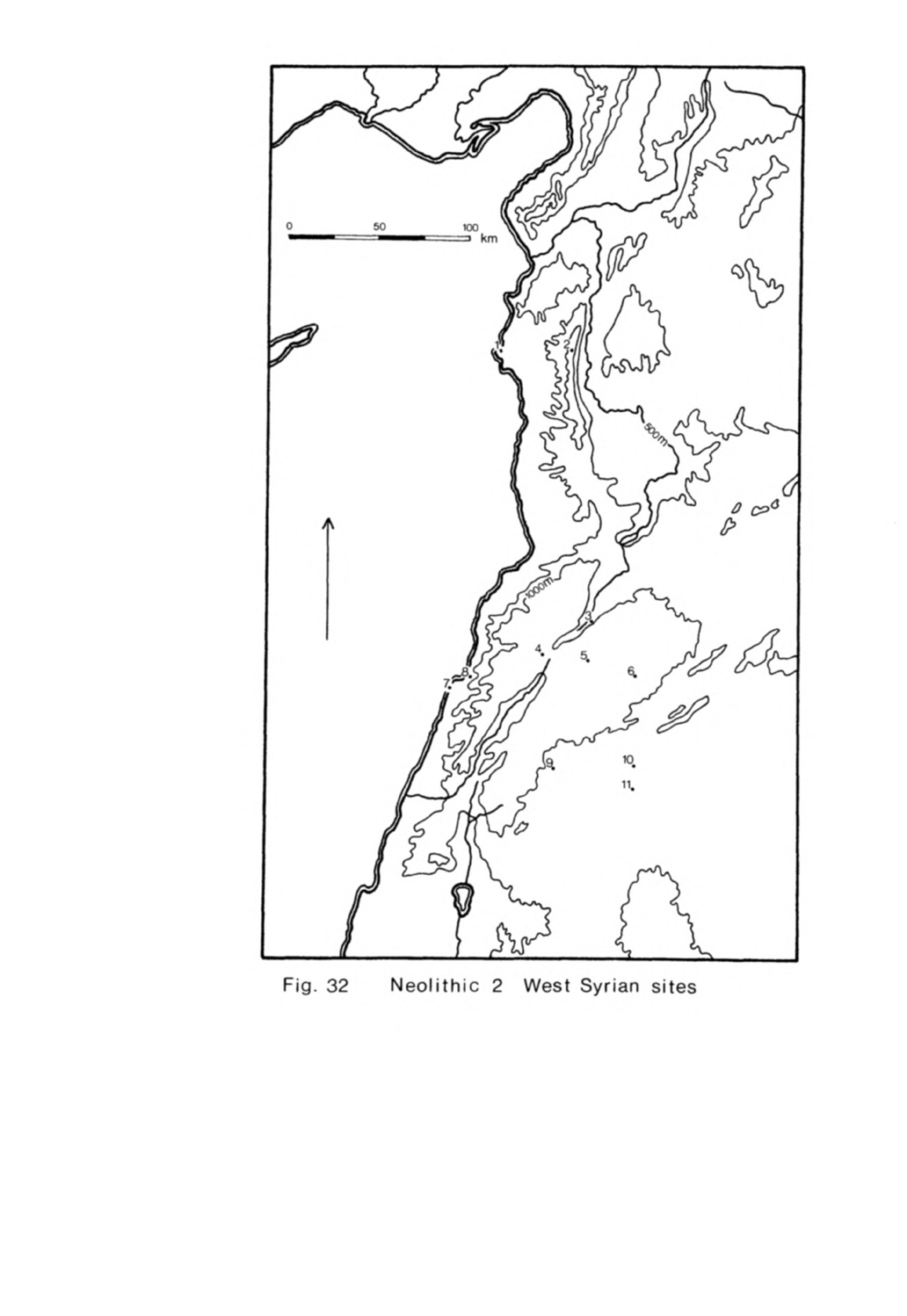

32

Neolithic

2

West

Syrian

sites

190

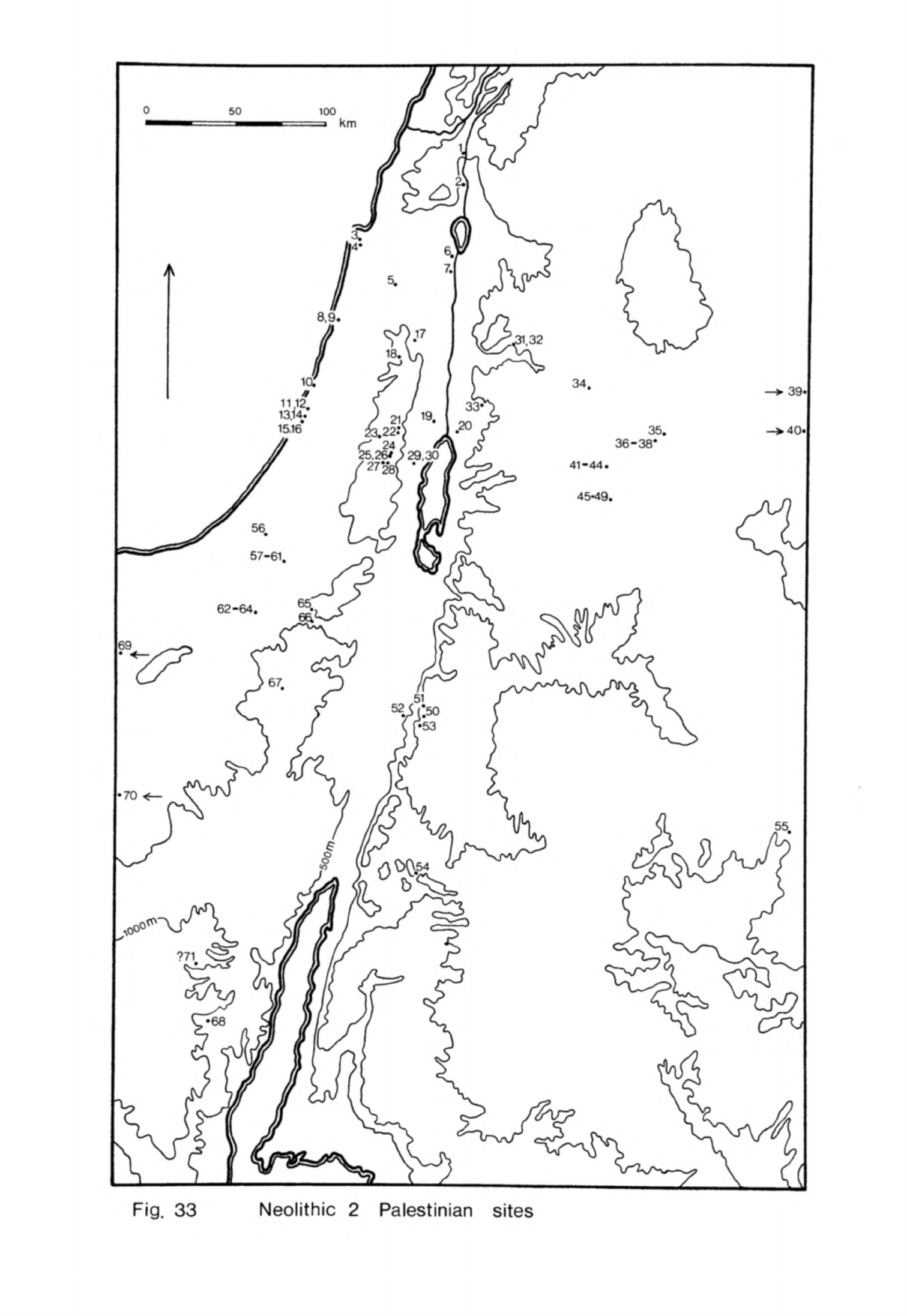

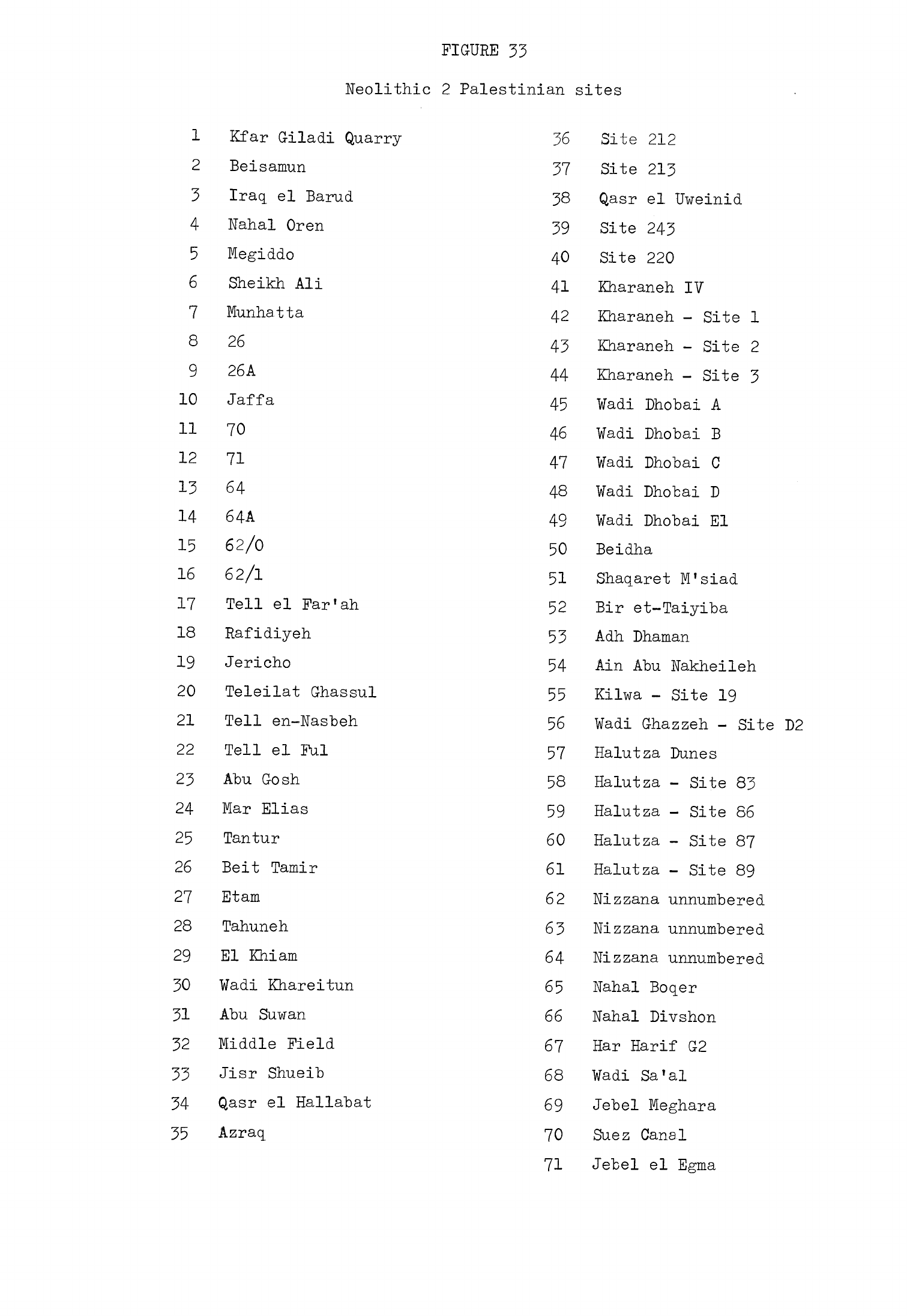

Fig.

33

Neolithic

2

Palestinian

sites

211

Fig.

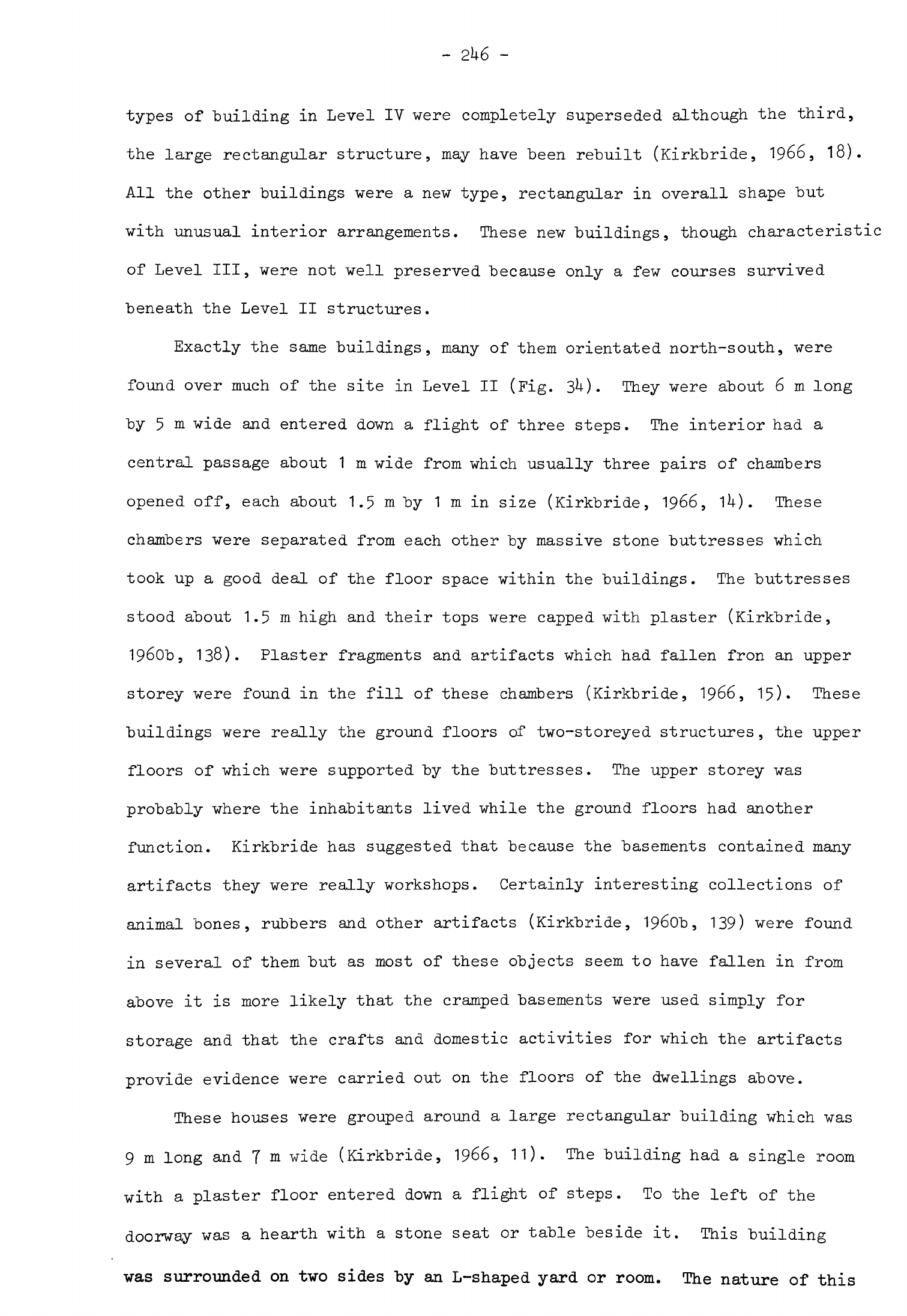

3^

Beidha

-

Level

II

buildings

(after

Kirkbride

and

Perrot)

2h6

Volume

2

Fig.

35

Extent

of

Neolithic

3

settlement

295

Fig.

36

Neolithic

3

North

Syrian

sites

299

Fig.

37

Horns

-

Amuq

points

(after

de

Contenson)

305

Fig. 38

Pattern-burnished

vessels

310

a

-

Tell

Judaidah

(after

Braidwood

and

Braidwood)

b

-

Byblos

(after

Dunand)

Fig.

39

Neolithic

3

South

Syrian

sites

328

Fig.

hO

Byblos

-

Ne"olithique

Ancien

houses

(after

Dunand)

331

Fig.

hi

Byblos

Neolithique

Ancien

333

a

-

sickle

blades

(after

Cauvin)

b

-

Byblos points

Fig.

h2

Byblos

-

Neolithique

Ancien

jars

(after

Dunand)

335

Fig.

h3

Byblos

-

Ne"olithique

Ancien

bowls

(after

Dunand)

336

Fig.

hh

Neolithic

3

Palestinian

sites

359

Fig.

lj-5

Distribution

of

Neolithic

h

sites

U12

Fig.

h6

Byblos

-

N£olithique

Moyen

flint

tools

(after

Cauvin)

Ul6

Fig.

hj

Byblos

-

Ne"olithique

Recent

flint tools

(after

Cauvin)

U17

Fig.

U8

Byblos

-

Ngolithique

Moyen

jars

(after

Dunand)

-

vi

-

Figures

and

Tables

(continued)

page

Fig.

h9

Byblos

-

Ngolithique

Re*cent

bowls

and

jars

(after

Dunand)

Fig.

50

Neolithic

h

South

Syrian

sites

Fig.

51

Neolithic

U

Palestinian

sites

Fig.

52

Jericho

-

Pottery

Neolithic

B

vessels

Fig.

53

Palestine

-

supplementary Neolithic

3

and

k

sites

Fig.

5U

Estimated

14

C

calibration

curve

to

10,000

B.C.

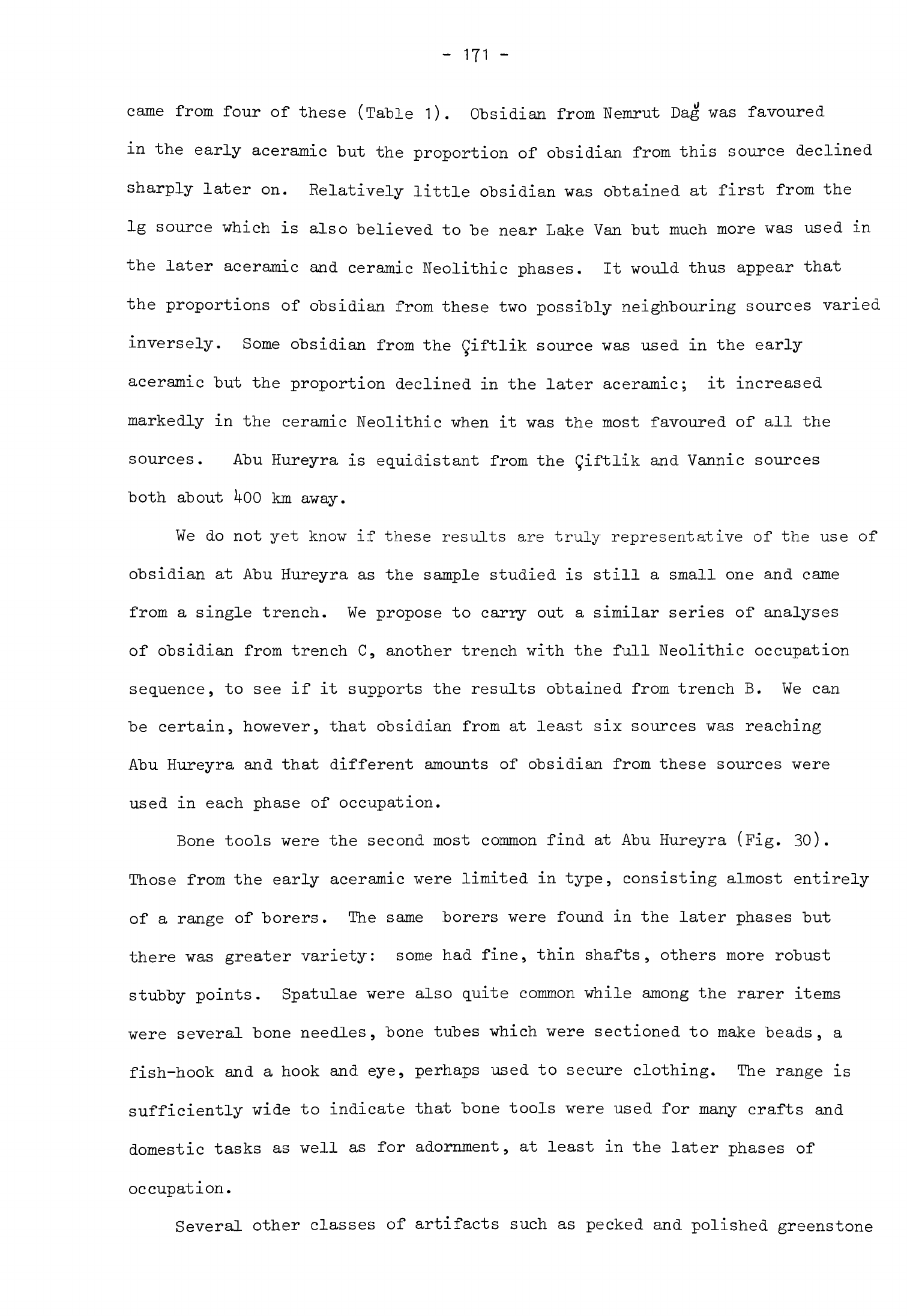

Table

1

Percentages

of

obsidian

in

each

cultural phase

at

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

171

Table

2

1*98

-

vii

-

ABSTRACT

THE

NEOLITHIC

OF

THE

LEVANT

A.M.T.

Moore

University

College

Doctor

of

Philosophy

Hilary

Term

1978

The

archaeological

evidence

for

the

Neolithic

of the

Levant,

considered

to

have

lasted

from

c.

8500

to

3750

B.C.,

is

presented

and

an

attempt made

to

explain

its

origins

and

development.

The

discussion

is

concerned

with

four

principal

themes:

(1)

the

transition

from

a

hunter-gatherer

to

a

farming

economy,

(2)

the

social

evolution

that

accompanied

this

economic

development,

(3)

population

growth

immediately

"before

and during the

Neolithic

and

(U)

the

modifications

in

settlement

patterns

which followed

these other

changes.

The

environmental

changes

which

occurred

at

the

end

of

the

Pleistocene

and

early

in

the

Holocene

are

believed

to

"be

of

fundamental

importance.

The

degree

of

their

influence

on

the

four

main

themes

is

examined.

The

effects

of

man's

own

changing

activities

upon

his

environment

are

also

considered.

The

Neolithic

of

the

Levant

is

divided

into

four

stages,

designated

Neolithic

1

to

U,

on

the

evidence

of changes

in

economy,

population,

settlement

patterns

and

cultural

remains.

Regional

groups

of

sites,

defined

"by

their

cultural

material,

may

"be

discerned

and

their

evolution

followed

from

one

stage

to

the

next.

The

detailed archaeological

evidence

is

examined

principally

for

the

light

it

throws

upon

the

development

of

the

four

main

themes

of

the

thesis and

the

contemporary

changes

in

environment.

It

is

argued

that

the

amelioration

of

the

environment

in

the

late

Pleistocene

created

a

greater supply of

wild

foods

for

man

which

stimulated

population

growth.

This

was

accompanied

by

increased

sedentism

and

the

development

of

agricultural

techniques.

In

Neolithic

2

agriculture

was

intensified

and

the

population

grew

further.

After

6000

B.C.

the

population

of

the

Levant

lived

in

permanent

settlements

supported

"by

agriculture

"but

these

were

concentrated

only

in

the

more

fertile

and

well-watered

areas of

the

Levant.

This

new

way

of

life

permitted

another

increase

in

population

in

Neolithic

^

despite

a

deterioration

in

the

environment.

-

viii

-

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This

thesis

was

written between

1975

and

1977

but

much of

the

information

I

have

used

was

obtained

in

studies

carried

out

as

far

back

as

1969

when

I

first

went

to

the

Near

East to

begin

research.

Throughout

I

have

benefited

from

the

encouragement and

advice

of

my

supervisor,

Dame

Kathleen

Kenyon.

She

introduced

me

to

Near

Eastern

Archaeology

by

inviting

me

to

participate

in

her

excavations

in

Jerusalem

in

1966.

She has

allowed

me to

study

all the

available

Neolithic

material

from

her

excavations

at

Jericho

and

to

use

whatever

information

I

needed

from

the

records

of

the

excavation.

Her

firm

criticism

has

clarified

my

thinking

and

writing

while

her

generous

praise

has

given

welcome

support.

I

owe

her

much.

I

studied under

Professor

J.D.

Evans

at

the

Institute

of

Archaeology

of

London

University

from

1967 to

1969.

It

was he

who

stimulated

my

interest

in

prehistory

and

the

problems

of

the

Neolithic.

His

humane

approach to

the

study

of

prehistory

has

influenced

my

own

work

and

I

am

grateful

to

him

for his

continued

interest

in

the

progress

of

my

research.

The

Queen's

College,

Oxford

awarded

me

a

Randall

Maclver

Studentship

from

1969

to

1971

and

the

British

School

of

Archaeology

in

Jerusalem

made

me

their

Annual

Scholar

from

1969

to

1970.

These

two

studentships

enabled

me

to

spend

a

year

and

a

half

travelling

through

much

of

the

Near

East,

visiting

ancient

sites

and

studying

museum

collections.

During

this

period

I

formed

a

working

knowledge

of

the

available

archaeological material

which

I

have

used

in

preparing

this

thesis.

In

1973

I

was

awarded

a

Gerald

Averay

Wainwright

Research

Fellowship

in

Near

Eastern

Archaeology

at

Oxford.

This

Fellowship

has

supported

me

while

I

prepared

the

text

of

the

thesis;

it

has also

allowed

me

to

continue

work

on

my

other research

projects,

in

particular

my

excavation

of

Tell

Abu

Hureyra.

I

wish

to

thank

the

Curators

and

staff

of the

Pitt

Rivers

Museum

and

Dr.

D.A.

Roe

of

the

Donald

Baden-Powell Quaternary

Research

Centre

for

-

ix

-

affording

me

facilities

and

practical

help

during

the

preparation

of

this

thesis.

In

all

my

sojourns

in

the

Levant

the

Directors

and

staff

of

the

Depart-

ments

of

Antiquities

in

each

country

have

readily

granted

me

permission

to

carry

out

my

research.

The

Curators

of

all

the

major

museums have

also

allowed

me full

access

to the

collections

of

material

in

their

charge.

It

will

be

evident

that

I

could have

accomplished

little

without

this

help.

These

authorities

have

also

frequently

given

me

much

other

practical

assistance

and

generous

hospitality

for

which

I

offer

my

grateful

thanks.

Very

many

other

people

from

high

officials

to

simple

peasants

and

nomads

have

helped

me

in

my

travels

so

putting

me

in

their

de~bt

in

ways

that

cannot

be

repaid.

It

is

a

pleasure

to

recall

and

acknowledge

these

innumerable

kindnesses

here

which

have

been

given

so

freely

in

the

true

tradition

of

Levantine

hospitality.

Many

archaeologists

and

other

scholars

in

several

countries

have

allowed

me

to

study

material

from

their

excavations

or

from

collections

in

their

care.

Much

of

this

information

has

been

incorporated

in

the

thesis.

Others

have

helped

me

by

analysing

samples

submitted

to

them.

All

have

willingly

answered

my

questions

and

discussed

matters

of

common

interest.

I

wish

to

thank

them

all

and

in

particular

the

following:

Prof.

E.

Anati

for

showing

me

his

material

from

Tell

Abu

Zureiq;

Prof,

and

Mrs.

Braidwood

for

showing

me

their

material

from

the

Amuq

tells,

Tell

Fakhariyah,

Tabbat

el

Hammam

and

other

sites

as

well

as

much

helpful

discussion;

M.

and

Mme

J.

Cauvin

for

showing

me

their

excavations

at

Mureybat

and

material

from

the

site,

and

for

several

useful

discussions;

M. H.

de

Contenson

for first

introducing

me

to

the

archaeology

of

Syria,

for

allowing

me

to

participate

in

his

excavations

at

Tell

Aswad

in

1971

9

for

access

to material

he

has

excavated

from

other

sites

and

for

many

other

kindnesses;

Mrs.

L.

Copeland

for

numerous

discussions

on

the

prehistory

of

the

Levant

and

much valuable

help

and

advice given

over

many

years;

Dr.

R.

Dornemann

for

allowing

me

to

study

his

material

from

El Kum;

M. M.

Dunand

for

permitting

me to

study

material from

Byblos

,

showing

me

his

excavations

-

x

-

and

much

kind

hospitality;

Prof.

R.

Dyson

for

allowing

me

to

see

material

in

the

University

Museum

of

the

University

of

Pennsylvania;

Pe"re

H.

Fleisch

S.J.

for

giving

me

free

access

to

the

collections

in

the

Universite*

Saint-

Joseph,

Beirut and

for

much

valuable

information;

Dr.

D.H.

French

for access

to

the

collections

of

the

British

Institute

of

Archaeology

in

Ankara;

Dr.

J.B.

Hennessy

for

showing

me

his

material from

Teleilat

Ghassul

and

for

much

other

help

in

Jerusalem;

G.

Hillman

for

analysing

the

plant

remains

from

my

excava-

tion

at

Tell

Abu

Hureyra;

P£re

F.

Hours

S.J.

for

information

about

his

excavations

at

Jiita,

help

in

the

Universite"

Saint-Joseph, Beirut

and

many

valuable

discussions;

J.

Kaplan

for

allowing

me

to

study

material from

several

of

his

excavations;

L.H.

Keeley

for

examining

several

tools

from

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

for

traces

of

microwear;

Prof.

C.C.

Lamberg-Karlovsky

for

access

to

the

collections

of

the

Peabody

Museum,

Harvard

University;

A.J.

Legge

for

information

about

his

work

at

Nahal

Oren

and

for

examining

the

faunal

remains

from

Tell

Abu

Hureyra;

Prof.

A.E.

Marks

for

allowing

me to

study

material

from

his

excavations

at

Southern

Methodist

University,

Dallas;

Prof.

M.J.

Mellink

for

access

to

the

material

from

Tarsus

kept

at

Bryn

Mawr

College;

Mrs.

J.

Crowfoot

Payne

for

showing

me

the

chipped

stone tools

from

Jericho

and

for

many

helpful

discussions;

M.

J.

Perrot

and

his

assistants

for

showing

me

material

from

his

excavations;

Dr.

B.

Rothenberg

for

allowing

me

to

see

material

from

sites

he

has

discovered

in

Sinai;

Dr.

B.

Schroeder

for

showing

me

material

from

his

excavations

at

Nacharini

and

for

information

about

his

research;

G.

de

G.

Sieveking

and

C.

Bonsall

for

access

to

material

from

Nahal

Oren

and

other

sites

in

the

British

Museum;

the

late

Father

J.

Sira

9

S.J.

for

showing

me

material from

the

first

excavations

at

Teleilat

Ghassul

and

surface collections

from

other

sites

kept

in

the

Pontifical

Biblical

Institute,

Jerusalem;

the

late

Pere

R.

de

Vaux

O.P.

for

allowing

me

to

study

material

from

his

excavations

at

Tell

el

Far'ah

at

the

Ecole

Bibliqjue

Saint-

Etienne,

Jerusalem

and

for

valuable

discussions;

S.E.

Warren

of

Bradford

University

for

all

his

help

in

our

joint

project

of obsidian

analyses,

and

Professor

T.

Cuyler

Young

and

his

assistants

for

showing

me

material

in

the

Royal

Untarid

.Museum,

Toronto.

INTRODUCTION

Man

has

been

a

mobile

hunter-gatherer

for

most

of

his

existence.

This

pattern

was

first

modified

during

the

Neolithic

when

sedentary

societies

were

formed

whose

members

lived

in

permanent

villages

and

depended

upon

agriculture

for

their

livelihood.

These

momentous developments

were

the

most

significant

changes

in

man's

way

of

life

since

his

evolution

as

a

species.

They

were

also

an

essential

first

step

in

the

subsequent

evolution

of

civilization.

The

origins

and

development

of

this

new

social

and

economic

system

in

the

Levant

will be

the

subject

of

my

thesis.

The

Levant

was

one

of

the

regions

in

the

Near

East

where

these

changes

in

society

and

economy

began.

This

happened

well before

the

adoption

of

the

new

way

of

life

by

mobile

societies

in

Europe

and

Africa.

Thus

we

should

study

the

Neolithic

in

this

region

if

we

are

to

understand

how

the

new

pattern

of

existence

came

about

and

what

its

immediate

consequences

were.

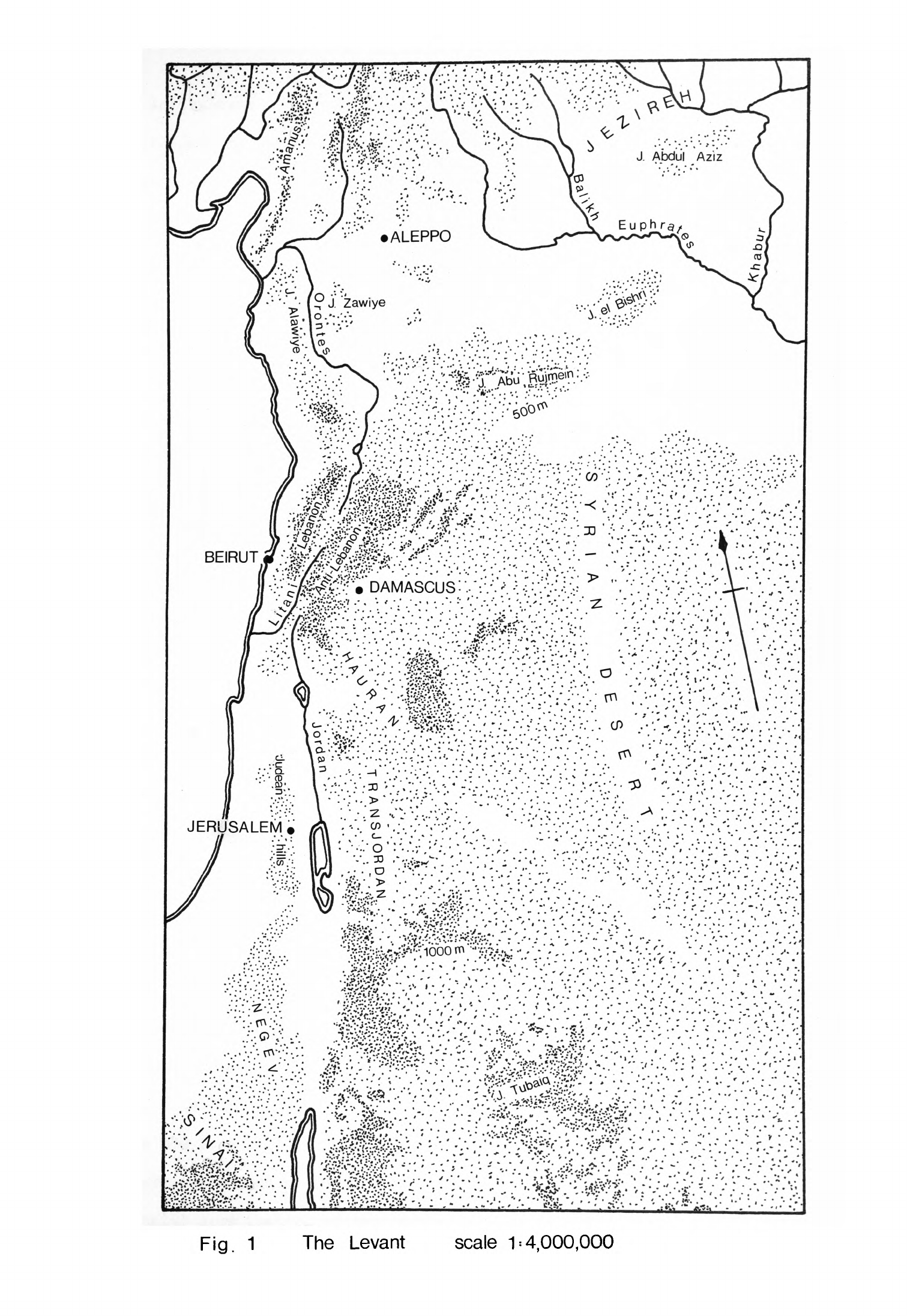

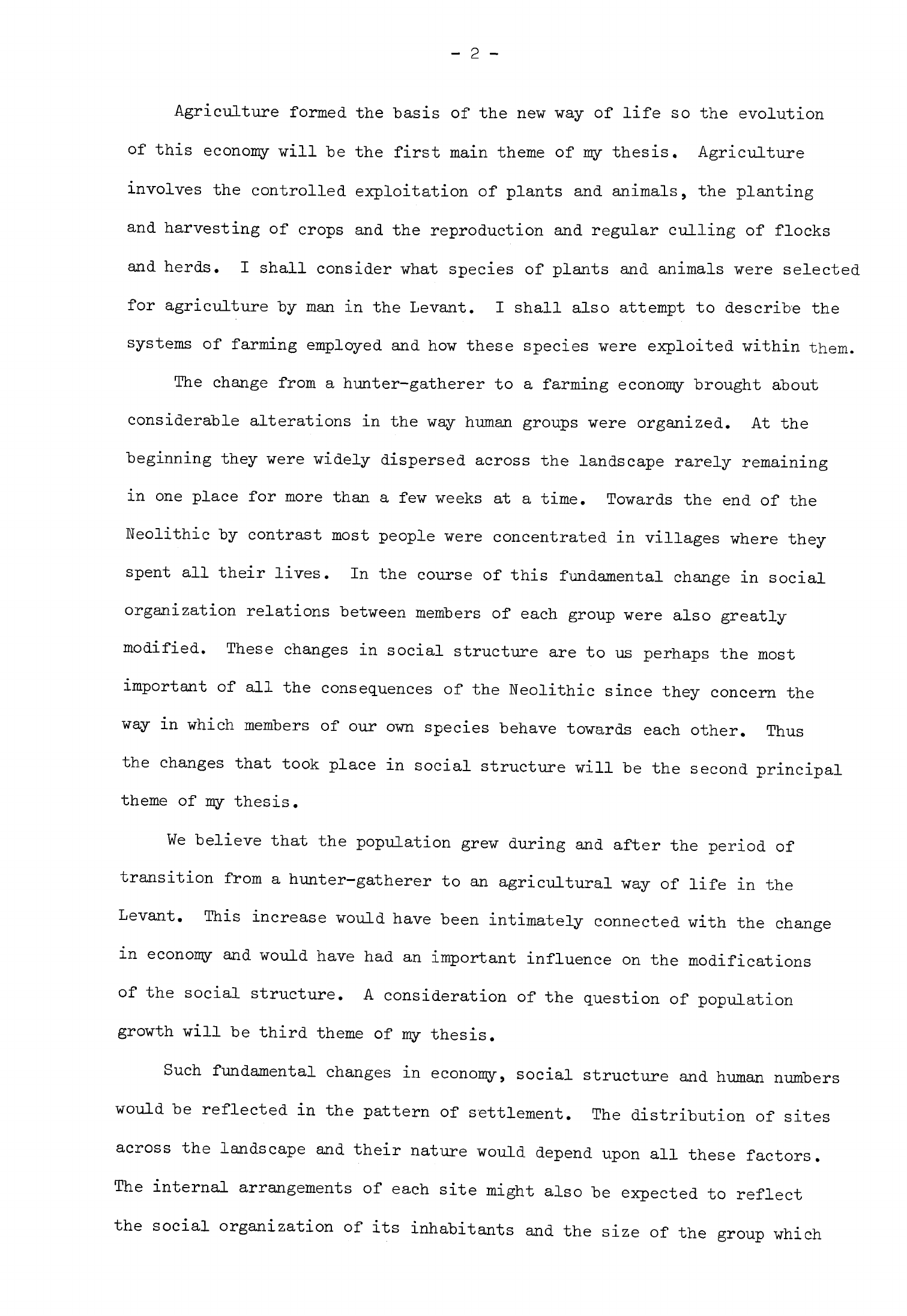

The

Levant

is

a

distinct

geographical

region

defined

by

natural

frontiers

(Fig.

1).

To

the

north

the

Taurus

Mountains

lie

between

it

and

the

Anatolian

plateau

while

to

the

east

and

south-east

the

Syrian

desert

separates

it

from

Mesopotamia

and

Arabia.

Sinai

and

the Gulf

of Suez

form

the

boundary

between

the

Levant

and

Egypt.

These

geographical

limits

also

served

as

cultural

boundaries throughout

the

period

that

I

shall

consider.

They

reinforced

the

regional

nature

of

Levantine

culture

and

its

development.

Thus

the

Levant

formed

both

a

geographical

and

cultural

unit

throughout

the

Neolithic

and,

indeed,

for

some

time

before

which

makes

it

a

particularly

convenient

region

in

which

to

study the

emergence

of

the

new

way

of

life.

It

is

also

the

region

in

the

Near

East

which

has

been

most

intensively

explored

by

archaeologists

interested

in

Mesolithic

and

Neolithic

communities

so

that

we

may

consider

the

origins

and

development

of

the

first

agricultural

societies

in

greater

detail

here

than

anywhere

else.

'.ffr;\.o>;p-«;•!.••.

<;^*

>£?•

<^

„>£.£;.

,'5-»

--.*•.;*-••*

'

.

.

J

*

**.

y»

O*

.*

-.*

.

:-t«^

r

:---:

:

^^.vl-.'^^;^n--

•«••.•.•:>:..•.-.»*.•

>

.

.-

•>

...

-..x...

c^s

r

'.•••

r.y.

•

Fig.

1

The

Levant

scale

1

=

4,000,000

-

2

-

Agriculture

formed

the

"basis

of

the

new

way

of

life

so

the

evolution

of

this

economy

will

be

the

first

main

theme

of

my

thesis.

Agriculture

involves

the

controlled

exploitation

of

plants

and

animals,

the

planting

and

harvesting

of

crops

and

the

reproduction

and

regular

culling

of flocks

and

herds.

I

shall

consider

what

species

of plants

and

animals

were

selected

for

agriculture

by

man

in

the

Levant.

I

shall

also

attempt

to

describe

the

systems

of

farming

employed

and

how

these

species

were

exploited

within

them.

The

change

from

a

hunter-gatherer

to

a

farming

economy

brought

about

considerable

alterations

in

the

way

human

groups

were

organized.

At

the

beginning

they

were

widely

dispersed

across

the

landscape

rarely

remaining

in

one

place

for

more

than

a

few

weeks

at

a

time.

Towards

the end of

the

Neolithic

by

contrast

most people

were

concentrated

in

villages

where

they

spent

all

their

lives.

In

the

course

of this

fundamental

change

in

social

organization

relations

between

members

of

each

group

were

also

greatly

modified.

These

changes

in

social

structure

are

to

us

perhaps

the

most

important

of

all

the

consequences

of

the

Neolithic

since

they

concern

the

way

in

which

members

of our own

species

behave

towards

each

other.

Thus

the

changes

that

took place

in

social

structure

will

be

the

second

principal

theme

of

my

thesis.

We

believe

that

the

population

grew

during

and

after

the

period

of

transition

from

a

hunter-gatherer

to

an

agricultural

way

of

life

in

the

Levant.

This

increase

would

have

been

intimately

connected

with

the

change

in

economy

and

would

have

had

an

important influence

on

the

modifications

of

the social

structure.

A

consideration

of

the

question

of

population

growth

will

be

third

theme

of

my

thesis.

Such

fundamental

changes

in

economy,

social

structure

and

human

numbers

would

be

reflected

in

the

pattern

of

settlement.

The

distribution

of

sites

across

the

landscape

and

their

nature

would

depend upon

all

these

factors.

The

internal

arrangements

of

each

site

might

also

be

expected

to

reflect

the

social

organization

of

its

inhabitants

and

the

size of the

group

which

-

3

-

lived

on

it.

Changes

in

settlement

patterns

will

be

one

of

the

most

important

items

of

archaeological

evidence

that

I

shall

consider

and

in

themselves

will

form

the

fourth

major

theme of my

thesis.

The

transition

from

mobile

hunting

and

gathering

which

had

characterised

man's

existence

throughout

the

Palaeolithic

to

a

Neolithic

agricultural

society

living

in

permanent

villages

took

place

about

the

time

of the

change

from

Pleistocene

to

Holocene.

During

this

period

the

temperature

began

to

rise

world-wide,

the

glaciers

retreated

and

the

sea

level

rose.

This

coin-

cidence

is

important

for

it

may

indicate

that

the

two

phenomena

were

related,

that

the

environmental

changes

created

conditions

which

were

favourable

for

the

development

of

the

Neolithic

way

of

life.

It

will

therefore

be

necessary

to

examine

in

detail the

climate

and

environment

of

the

Levant

in

the

late

Pleistocene

and

to

see

how

these

were

modified

during

the

early

Holocene.

This

will

be

the

subject

of

Chapter

1.

In

subsequent

chapters

I

will

examine the

effects

of

the

environmental

changes

on

the

factors

which

form

the

main

themes

of the thesis.

Man

himself

was not

simply

affected

by

alterations

in

his

environment

but

contributed

to

these

changes

by

exerting

his

own

influence

on

his

surroundings.

During

the

Neolithic,

perhaps

for

the

first

time,

he

came

to

play

a

significant

role

in

determining

the

nature

of

his

environment.

I

shall

discuss

the

evidence

we

have

for

the

effects

of

man

on

his

surroundings

in

appropriate

sections

of

the

thesis.

The

origins

of

the

Neolithic

way

of

life

can

only

be

understood

if

we

know

how

the

people

of

the

Levant

lived

in

earlier

periods.

To

this

end

I

shall

consider

the

Mesolithic

of

the

Levant,

the

stage

preceding

the

Neolithic,

in

Chapter

2

of

the

thesis.

I

shall

examine

in

outline

the

settlement

pattern,

economy,

population

and

social

structure

of

Mesolithic

communities

in

the

Levant

since

these

concern

the

major

themes

of

the

thesis.

The

changes

in

economy,

social structure,

population

and

settlement

that

occurred

during

the

Neolithic

can

only

be

determined

by

a

thorough

enquiry

into

all

the

archaeological

evidence.

It

will

be

necessary

to

consider

most

of

the

known

sites

themselves

and

their

distribution

as

well

as

the

remains

that

have

"been

found

on

them

in

excavation,

survey

or

by

chance.

The

organic

remains

found

on

some

sites are

the

most

important

source

of

evidence

for

the

economy

"but

I

shall

also

consider other

material

that

has

a

bearing

upon

this

main

theme.

The

relative

dates

when

each change

occurred

provide

the

framework

within which

all the

other kinds

of

evidence

must be

ordered.

These

dates

depend

upon

the

chronology

of

the

evolution

of

the

Neolithic

derived

from

absolute

dating and

the

comparative

stratigraphy

of

sites

and

typology

of

artifacts.

I

shall

consider

these

topics

in

detail

at

appropriate

places

in

each

chapter.

The

enquiry

into

the

archaeological

evidence

will

form

the

bulk

of

the

thesis

from

Chapters

3

to

6.

It

will

be seen that

I

conclude

from

this

that

the

evolution

of

the

Neolithic

of the

Levant

falls

into

four

stages.

In

each

chapter

I

shall

first

present

the

archaeological

evidence

for

the

successive

stages.

I

shall

then

consider

changes

in

settlement

patterns,

economy,

social

structure

and

population

in

relation

to

this

evidence.

My

conclusions

on

how

the

Neolithic

began

and

subsequently

developed

will

be

presented

in

Chapter

7.

Much

of

the thesis

will

be

necessarily

devoted

to

establishing

through

a

detailed

description

of

the

archaeological

material

what

happened

in

the

Neolithic.

I

wish

to

take

the

enquiry

further

than

this

by

attempting

to

explain

why

the

changes

that

I

shall

present,

particularly

in

economy,

social

structure and

population,

took

place.

The

scope

of

the

discussion

will

be

broad

since

it

concerns

one

of

the

most

important

changes

that

has

taken

place

in

man's

way

of

life

as

it

occurred

in a

large

region

and

over

a

considerable

span

of time.

It

will

afford

an

opportunity

to

consider

one

of

the

problems

of

modern

archaeological

theory:

is

there

one

all-embracing

model

or

explanation

by

which

the

changes

I

shall

describe

may

be

understood?

Is

there

any

single

event

or

cause

to

which

all

that

followed

may be

attributed?

Were

there

several

factors

which

determined

the

course

of

events?

-

5

-

On

the

other

hand,

did the

Neolithic

of

the

Levant

come

a"bout

as

the

result

of some

haphazard

conjunction

of

circumstances?

Or

are

there

other

explana-

tions

for

this

fundamental

change

which

lie

between

the

two

extremes

of

these

theoretical

approaches?

-

6

-

Chapter

1

THE

ENVIRONMENT

OF

THE

LEVANT

IN

THE

LATE

PLEISTOCENE

AND

EARLY

HOLOCENE

The

environment

of

the

Levant

at

the

close

of

the

Pleistocene

and

early

in

the

Holocene

was

until

recently

poorly

understood.

It

had

long

"been

thought

that

changes

in

the

environment

at

the

end

of

the

Pleistocene

contributed

to

the

evolution

of

the

Neolithic

way

of life

but

the

influence

of

these

changes

could

not

be

properly

assessed.

Recent

studies

in

geo-

morphology, palynology

and

palaeozoology

have

produced new

evidence

on

which

to

base

an

outline

reconstruction

of

the

environment

in

the

late

Quaternary.

I

will

begin

this

chapter

by

discussing

certain

general

factors

which

affected

the

environment

of

the

whole

Levant.

I

will

then

consider

the

evidence

for

the

climate,

landscape

and

vegetation

of

each

region

of

the

Levant

and

how

they

were

modified,

first

in

the

late

Pleistocene

and

after

in

the

early

Holocene.

In

northern

latitudes

the

late

Pleistocene

is

marked

by

the

Wtlrm/

Wisconsin

glaciation.

The

Near

East

was

not

directly

affected

by

the

advance

of

the

European

ice

sheets

but

its

climate

was

significantly

altered

none-

theless.

An

indication

of

these

climatic

changes

has

been

obtained from

studies

of

the

fauna

and

sediments

in

several

deep-sea

cores.

Analyses

of

cores

drilled

in

the

Red

Sea

have

determined

that

the

climate

was

cooler

and

more

humid

there

during

the

period

of

the

last

glaciation

(Herman,

1968,

3^5)

.

Two

other

deep-sea

cores

have

been

drilled

in

late

Quaternary

deposits

in

the

eastern

Mediterranean,

one

between

Cyprus

and

Crete

(no.

189)

and

the

other

west

of

Crete

(V

10.67).

Oxygen

isotope

analysis

of

these

cores

has

shown

that

the

temperature

of

the

Mediterranean

fell

considerably

during

the

period

of the

last

glaciation

(Emiliani,

1955

9

90;

Vergnaud-Grazzini,

Herman-Rosenberg,

1969,

288}

and

studies

of

the

fauna

of

core

V

10.67

have

confirmed

this

conclusion

(Vergnaud-Grazzini,

Herman-Rosenberg,

1969,

2b3).

There

is

some

doubt

about

how

much

the

temperature

actually

decreased

at

this

-

7

-

time

but recent

work

suggests

that

the

estimate

of

Vergnaud-Grazzini

and

Herman-Rosehberg

of

a

fall

of

between

5°

and

10 C

is

the

more

reasonable

(Farrand,

1971, 53*0.

This drop

in

temperature

caused

increased

glacial

activity

in

the

mountainous

regions

of

the

Eastern

Mediterranean.

The

present

relict

glaciers

in

the

Taurus

expanded

considerably

and

it

is

estimated

that

the

snowline

lay

about 1000m

lower

than

today

(Messerli,

1967,

139),

that

is

at

about

2650m.

It

is

also

believed

that

there

were

glaciers

in

the

Mountains

of

Lebanon

and

on

Mount

Hermon

(Kaiser,

1961,

131ff;

Klaer,

1962,

97;

Messerli,

1966,

U6ff)

but

there

is

a

divergence

of

opinion

over

how

much

the

snowline

was

depressed

in

the

Levant.

Klaer

claims

that

the

permanent

snowline

today

would

lie

between

3200

and

3^00m

(1962,

97)

but

Messerli

estimates that

it

would

be

as

high

as

3700m

(1966,

61),

that

is

above

the

summits

of

the

highest

mountains

in

the

Lebanon.

Both

derive

their

different

estimates

from

studies

of

present

snowfall.

Klaer

and

Messerli

have

also

examined

the

evidence

for

glaciation

in

the

mountains

and almost

agree

on

the level

of

the

permanent

snowline

during

the

Wurm.

Klaer

thinks

that

it

lay

between

2750

and

2850m

and

so

fell

about

500m

(1962,

117);

Messerli

believes

that

the

snowline

was

at

about

2700m

(1966, 61),

a

much

greater

fall

of

about

1000m.

Messerli's estimate

of

a

depression

of

about

1000m

would

agree

better

with

the

evidence

from

the Taurus and

so

may

be

the

more

likely.

If

a

fall

in

the air

temperature

was

the

sole

cause

of

this

lowering

of

the

snowline

then

it

would

need

to

have

dropped

about

6

or

7 C

(Messerli,

1967

9

207;

Farrand,

1971,

550),

an

estimate

which

agrees

broadly

with

the

evidence

of

the

deep-sea

cores.

Studies of

the

sediments

of

some

cave

sites

in

the

Levant

have

shown

that

these

were

deposited

under

the

prevailing

cooler climate

of

the

last

glaciation.

This

is

most

apparent

at

the

inland

sites

of

Jerf

'Ajla

and

Yabrud

which

were

affected

by

continental

conditions.

Frost

weathering

could

be

detected

throughout

the

Mousterian

and

Upper

Palaeolithic

sequence

-

8

-

at

Jerf

'Ajla

(Goldberg,

1969,

750)

although there

were

some

fluctuations

reflecting

warmer

climatic

phases.

It

is

also

believed

that

the

top

five

metres

of

deposit

at

Yabrud

I,

which

includes

the

Mousterian

layers,

was

laid

down

under

cooler

conditions

(Farrand.,

1965^,

^1ff).

Although

winters

can

be

cold

in

these

areas

today

they

are

rarely

cool

and

moist

enough

to

cause

significant

frost

weathering.

Farrand

has

detected cryoturbation

in

the

Levallois-Mousterian

and

Upper

Palaeolithic

layers

at

Jebel Qafzeh

(1971,

553;

1972,

233)

near

Nazareth.

This

site

lies on

the edge

of

the

Galilee

hills

at

an

elevation

of

220m

(Bouchud,

197^,

87),

sufficiently

high

apparently

to

have

experienced

frost

weathering.

The

climate

at

coastal

sites

such

as

Tabun

was

also

some-

what

cooler

during

the

last

glaciation

(Jelinek

et_al.,

1973,

177)

"but

not

cold

enough,

apparently,

to

cause

significant

frost

weathering

(Farrand,

1971» 553).

The

evidence

from

the

caves

thus

supports that

from

other

sources,

indicating

that

during

the last

glaciation

the

temperature

in

the

Levant

fell

by

several

degrees.

The

advance

of

the

ice

sheets

absorbed

water

from

the

oceans

and

markedly

lowered

sea-levels.

During

the

later

Wurm

sea-levels

throughout

the

world

fell

by

perhaps

100

or

150m

(Fairbridge,

1961,

152;

Milliman,

Emery,

1968,

1123;

Butzer,

1972,

217)

which

considerably

altered

the

configuration

of

the

coastline

of

the

Levant.

Taking

the

more

modest

estimate

of

a

fall

of

100m,

the

shoreline

in

Palestine

would

have lain

15

km

further west

across

a

gradually

sloping

coastal

plain.

In

Lebanon

and

southern

Syria

the

coastal

plain

would

have

been

about

5

km

wider

than

now,

sloping

down to

the

sea

and

dissected

by

wadis.

North

of

Lattakia

it

would

have

been

only

2

km

wider

with

a

steep

slope.

The

displacement

of

the

coastline

has

important

implications

for

the

pattern

of

later

prehistoric

settlement

as

we

see

it

today.

All

Terminal

Palaeolithic

and

Mesolithic

sites

and

some

early

Neolithic

ones

now

situated

near

the

sea

would

have

lain

well

inland

at

the

time

they

were

inhabited.

-

9

-

This

includes

the

sites

in

the

coastal

dunes

and

around

Mount

Carmel

in

Palestine

as

veil

as

many

of

the

shelter

sites

in

Lebanon.

An

open

coastal

plain

would

have

lain

to

the

west

of

these

sites

so

their

environments

would

have

appeared

much

more

favourable

for

settlement

then than

they

do

now.

Almost

certainly

many

more

prehistoric

sites

were

situated

on

the

coastal

plain

which

are

now

drowned.

These

would

have

included

almost

all the

sites

whose

inhabitants

might

be expected

to

have

supported

themselves

partly

by

fishing.

Our

present

views about

the

economy

and

settlement

pattern

of

sites

on

the

seaward

side

of

the

coastal

hills

and

mountains

of

the

Levant

will

thus

be

distorted

if

we

fail

to

allow

for this

evidence

which

we have

lost.

Palaeotemperature

studies

of

deep-sea

cores

from

the

Atlantic, Caribbean

and

Pacific

indicate

that

the

temperature

gradually

began

to

rise

worldwide

between

20,000 and

15,000

B.P.

(Emiliani,

Shackleton,

197^,

figs.

3,

U).

After

15

9

000

B.P.

it

rose

sharply until

it

reached

a

maximum

about

5000

B.P.

The

palaeotemperature

curves

derived

from deep-sea

cores

mask

almost

all

the

minor

fluctuations

in

temperature

that

occurred

during

this

period

but

one

temporary

fall

in

temperature

about

10,000

B.P.

lasted

long

enough

to

be

detected

in

the

Caribbean

cores

(Emiliani,

1972,

fig.

3).

This

has

been

equated

with

the

Post-Allero'd

or

Younger

Dry

as

phase

of

cooler climate

in

northern

Europe

(Lamb,

Woodroffe,

1970,

Uo).

As

the

temperature

increased

so

the

glaciers

melted

and

the

level

of

the

oceans

around

the

world

began

to

rise;

this

process

had

certainly

begun

by

12,000

B.C.

(Milliman,

Emery,

1968,

1123)

and

perhaps earlier

before

1U,000

B.C.

(Farrand,

1965a,

396;

Shackleton,

Opdyke,

1973,

U6).

There-

after,

although

interrupted

by

several

short

stages

of

retreat

(Curray,

1961,

1?07ff;

Fairbridge,

1961,

15^ff)

the

level

of

the

oceans

rose

rapidly

until

about

5000 B.C.

and

then

more

slowly

until

it

reached

its

present

level

about

UOOO

(Fairbridge,

1961,

fig.

1U;

Shackleton,

Opdyke,

1973,

U6)

or

3000

B.C.

(Butzer,

1972, 530).

There

is

no

general

agreement

on

the

actual

levels

of

the

sea

worldwide

at

particular

times

during

this

period

although

-

10

-

one can

gain

some

idea

of

the

rapidity

of

the

transgression

by

comparing

estimates

based

on

evidence

from

the

continental

shelves.

Thus

by

10,000

B.C.

Fairbridge

estimates

that

the

sea

had

risen to

about

Uo

or

50m

below

its

present

level

(1961,

fig.

1U)

although

Milliman

and

Emery

believe

it

still

to

have been

much

lower

(1968,

figs.

1,2):

at

TOGO

B.C.

perhaps

15

(Fairbridge,

1961,

fig.

15)

or

as

much

as

50m

lower

(Milliman,

Emery,

1968,

figs.

1,2):

at

5000

B.C.

10

to

30m

below

present

levels.

The

most

recent

curve

of

glacio-eustatic

sea-level

fluctuations

during

the

Quaternary

is

that

published

by

Shackleton

and

Opdyke

(1973,

fig.

7).

This

was

derived from

oxygen

isotope

analysis

of

foraminifera

in

a

core,

Vema

28-238,

drilled

in

the

sea

bed

of

the

Pacific.

This

new

evidence

also

indicates

that

the

level

of

the

sea

rose

rapidly

once

the

ice

began

to

melt.

The

curve agrees

better

with

that

of

Fairbridge

than

of

Milliman

and

Emery;

Shackleton and

Opdyke

estimate that

at

10,000

B.C.

the

sea

would

have

been

about

30

to

UOm

below

the

present

level.

These estimates

may

not

correspond

exactly

with

the

Mediterranean

rise

in

sea-level

but

as

a

recent

study

has

shown

that

there was

little

tectonic

movement

along

the

Levant

coastline

during

this

period

(Sanlaville,

quoted

in

Copeland,

1975

9

318)

they

probably

give

a

rough

indication

of

the

rate

of

change.

They

suggest

that

the

coastal

plain

was

sufficiently

open

to

facilitate

communications

along

the

Levant

coast

until

about

7000

or

even

as

late

as

5000

B.C.,

that

is

during

the

later

Neolithic.

Thereafter,

although

the

level

of

the

sea

rose

further

and there

were

additional

minor

fluctuations

(Sanlaville,

1969,

290),

this

had

no

significant

effect

on

the

pattern

of

settlement.

Movement

along the

coast

became

more

difficult,

particularly

at

the

foot

of

the

Mountains

of

Lebanon

between

Beirut and

Tripoli.

Studies

of

shorelines,

sediments

and

pollen

samples

have

shown

that

there

were

several

marked

oscillations

in

climate

during

the

period

of

the

last

glaciation

and

after.

Unfortunately

these

oscillations

are

not

well

dated

and

it

is

difficult

anyway

to

correlate

the

evidence

from

these

different

-

11

-

sources.

Thus

there

is

no

general

agreement

on

the

pattern

of

climatic

change

in

the

Levant during

the

late

Pleistocene

and Holocene.

Some

authorities

believe

they

can

detect

a

detailed

sequence

of

climatic

fluctua-

tions

which

matches

the

well-documented

record

of

northern

Europe

(Horowitz,

1971,

27Uff)

while

others

think

that

the

evidence

is

insufficiently

detailed

for

such

a

precise evaluation

(Farrand,

1971,

559;

Butzer,

1975,

389,

kok).

Nevertheless,

there

is

now

enough

evidence

from

a

variety

of

sources

to

attempt

a

reconstruction

of

the

environment

at

the

close

of

the

Pleistocene

and

in

the

early

Holocene,

even if

the

absolute

chronology

is

still

uncertain,

Late

Pleistocene

During

much

of

the

period

of

the

last

glaciation

the

inland

"basins

of

Palestine

and

TransJordan

were

filled

with

"pluvial"

lakes.

The

largest

of

these

was

the

Lisan

lake

which

flooded

much

of

the

Rift

valley

at

present

occupied

by

the

Sea

of

Galilee,

the

River

Jordan

and

the

Dead

Sea.

This

lake

came

into

existence

after

about

70,000

B.P.

and

was

maintained

at

its

highest

level

from

about

50,000

to

20,000

B.P.

during

the

"Lisan"

Stage

(Neev,

Emery,

1967,

26,

fig.

16).

It

was

then

about

220

km

long

although

no

more

than

17

km

wide

and

its

surface

was

at

about

180m

below

mean

sea

level,

some

200m

above

the

present

surface

of

the

Dead

Sea

(Neev,

Emery,

1967,

25).

It

is

believed

that

the

Lisan

lake

was

created

during

a

period

of

increased

precipitation,

or

at

least

at

a

time

when

there

was

more

run-off

of

surface

water

and

less

evaporation

in the

Rift

valley

(Neev,

Emery,

1967,

26).

The

ecological

equilibrium

in

this

region

is

easily

disturbed

so

even

small

changes

in

climate

can

have

a

great

effect

on

the

environment.

It

has

been

calculated

that

a

rainfall

increase

of

as

little

as

200m

in

the

Rift

valley

catchment

would

be

sufficient

to

create

the

Lisan

lake

(Ben-

Arieh,

196U,

k6}

without

any

change

in

other

variables.

We

know

from

other

evidence

that

the

temperature

fell

by

at

least

5°C

during

the

last

glaciation

-

12

-

which,

as

Butzer

has

pointed

out

(1975,

393)

would

have

increased

effective

precipitation

by

reducing

evaporation.

It

may

be

that

there

was

little

more actual

rainfall

but

combined

with

the

drop

in

temperature

this

was

enough

to

fill

the

Lisan

basin.

Although

the

lake

was

so

large

it

was

always

too

salty

for

fish

and

molluscs

to

live

in

it

(Neev,

Emery,

196?

9

8"0

and

thus

useless

to

man

as

a

source

of

food.

Because

of

its

length

it

would

also

have

hindered

rapid

communication

between

the

Judean

uplands

and

TransJordan.

During

the

last

glaciation

another

very

large

lake

existed

in

the

Jafr

basin

to

the

east

of

Maan

(Huckriede,

Wiesemann,

1968,

79)

and

smaller

ones

in

the

Azrak

depression

and

perhaps

elsewhere

in

TransJordan.

The

Jafr

lake

was

between

1000

and

1800

sq

km

in

area

(Huckriede,

Wiesemann,

1968,

78).

It

was

a

freshwater

lake

and

its

sediments

were

rich

in

molluscs. An

upper

layer

of

the

lake deposits

has

been

dated

to

27,700

±

870

B.P.

Hv-1719

(Huckriede,

Wiesemann,

1968,

81).

Further

north

the

Damascus

basin

was

also

flooded

during

the

Wtirm

and

there

was

a

small

lake

in

the

Barada

gorge

(Kaiser

et

al.,

1973,

279,

299).

Large

bodies

of

freshwater

such

as

the

Jafr

and

Damascus

basin

lakes

would

have

created

highly

favourable environments

for man.

They

contained

an

abundance

of

fish

and

molluscs

while their marshy

shores

would

have

attracted

wildfowl

and

game.

Their

surface area was

sufficiently

great

for

evaporation

to

create

greater

humidity

in

the region

than

now.

This

would

have

made

more

moisture

available

for

plants

through

both

increased

precipitation

and

dew.

About

18,000

B.C.

the

Lisan

lake

shrank

until

its

surface

lay

at

about

37m

below

mean

sea level

(Neev,

Emery,

1967,

26);

this

happened

very

quickly,

perhaps

within

a

millennium.

The

water

level

of

the

lake

dropped

so

much

during

this

"Dead

Sea"

Stage

that

the

Lisan

split

into

four

relict

lakes:

the

Sea

of

Galilee,

a

lake

at

Beth-Shan

and

two

lakes

in

the

Dead

Sea

basin.

It

is

believed

that this

rapid

transformation

was

partly

caused

by

tectonic

-

13

-

subsidence

but

either

a

decrease

in

precipitation

or

increase

in

evaporation

or

a

combination

of

the

two

must

also

have

taken

place.

The

water

level

remained

low

for

several

millennia

but

then

rose

again,

apparently

because

of

an

increase

in

available

moisture.

This

phase

of

higher

water

level

is

dated

by

a

single

14

C

date

of

7900

+

150

B.C.

(Neev,

Emery,

1967,

28).

The

Jafr

lake

gradually

dried

up

sometime

after

26,000

B.C.

(Huckriede,

Wiesemann,

1968,

80,

82),

a

process

that

is

probably

associated

with

the

demise

of

the

Lisan

lake.

There

followed

a

very

arid

stage

of

uncertain

length.

This

was

succeeded

by

a

phase

of

more

effective

precipitation

during

which

mudflats

were

formed

in

the

Jafr

basin

(Huckriede,