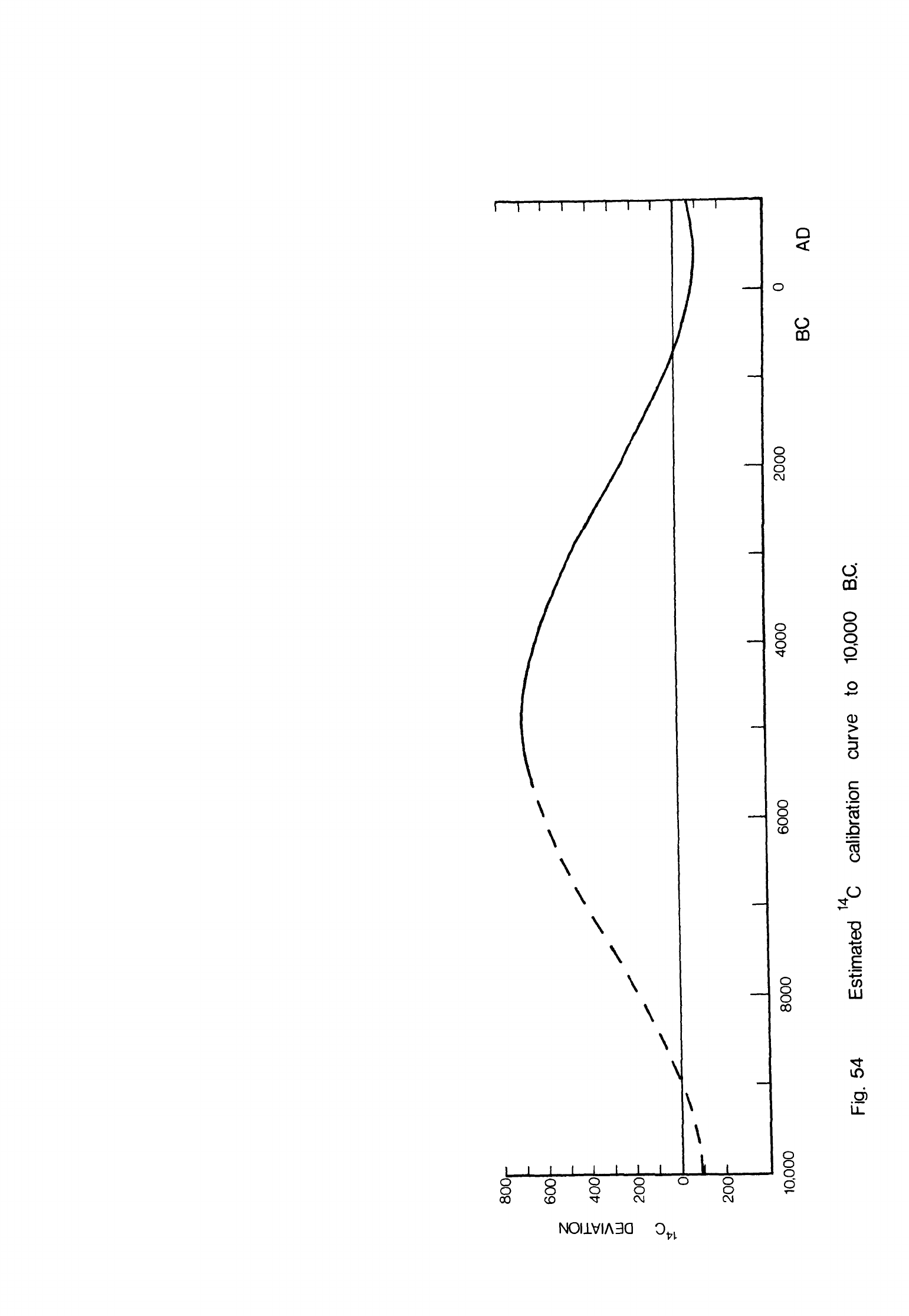

THE

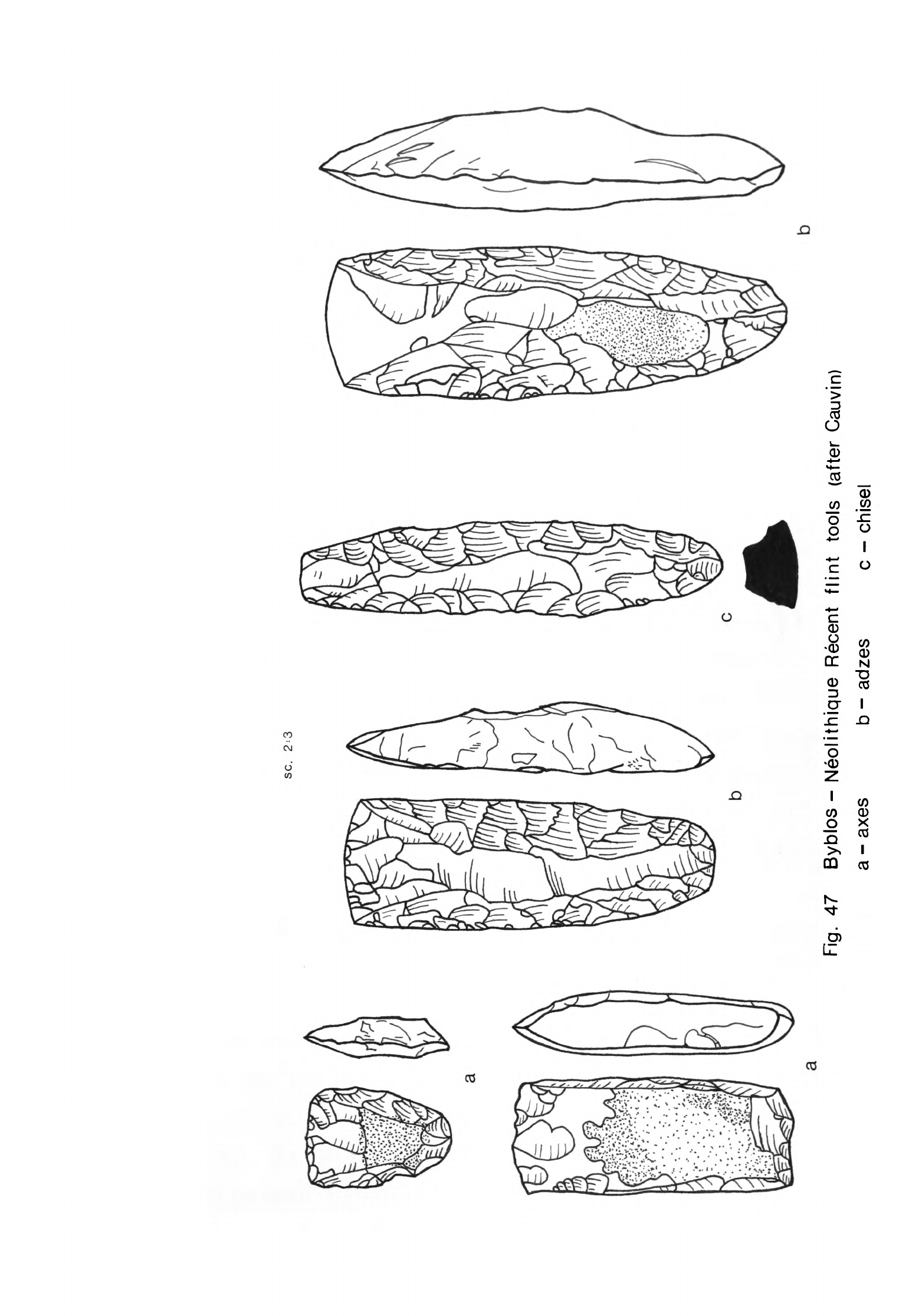

NEOLITHIC

OF

THE

LEVANT

A.M.T.

Moore

University

College

Volume

2

Thesis

submitted

for the

Degree

of

Doctor

of

Philosophy,

Oxford

University

1978

Chapter

5

NEOLITHIC

3

About

6000

B.C.

there

is

evidence

in

the

archaeological

record

of

marked

changes

in

material

remains,

economy,

settlement

patterns

and

social

organi-

zation

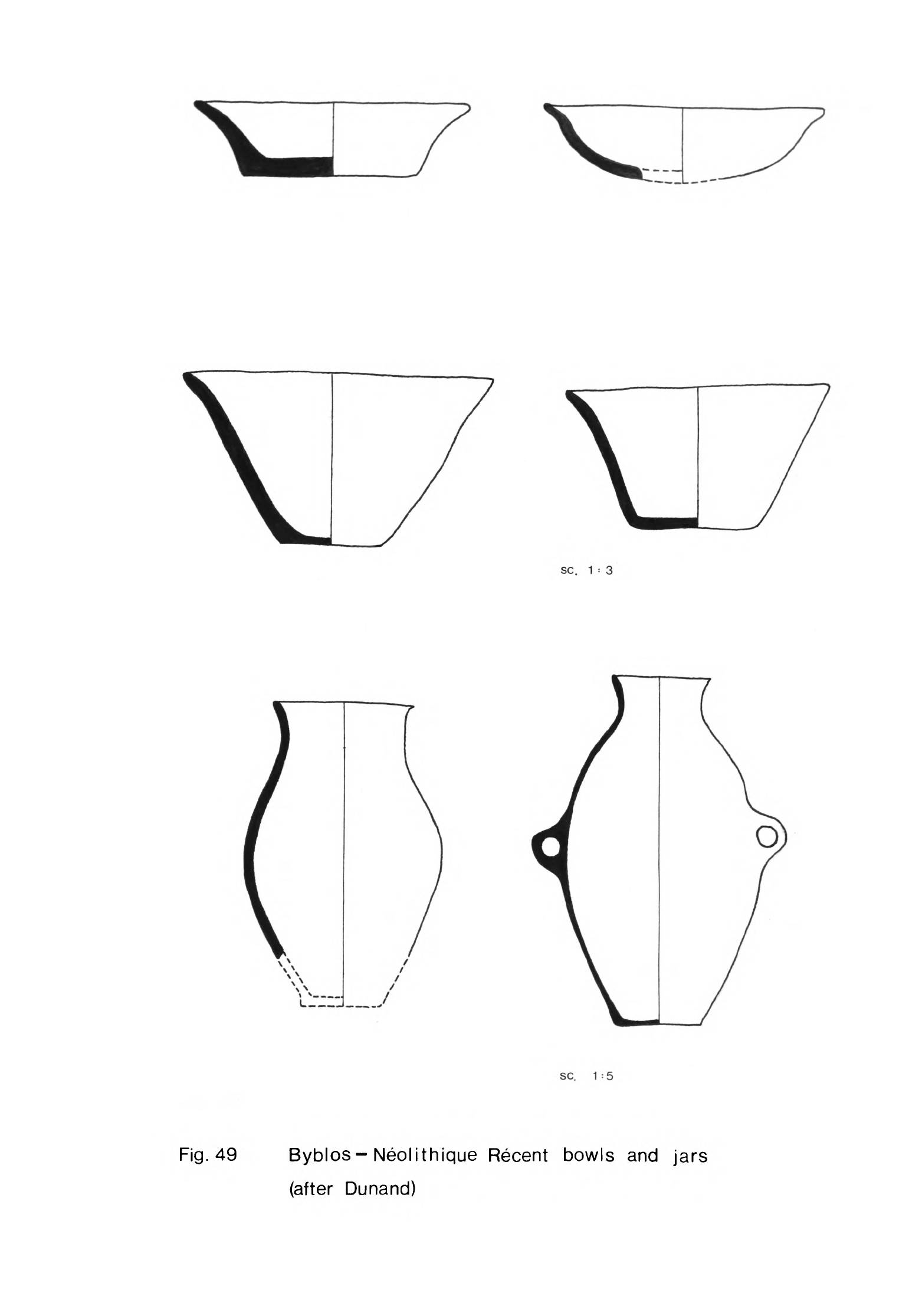

signifying

the

emergence

of

a

new

stage

in

the

Neolithic

of the

Levant

which

I

shall

call

Neolithic

3.

The

Neolithic

2

tradition

of

building

recti-

linear

single

or

multiple-roomed

mud-brick

houses

was

continued

on

some

Neolithic

3

sites

but

on

others

the

inhabitants

lived

in

sub-circular

pit

dwellings.

Other

large

pits

which

may have

served

as

working

or

cooking

hollows

are

another

conspicuous

feature

of

many

Neolithic

3

settlements.

The

characteristic

flint

industry

of

Neolithic

2

was

modified

in

Neo-

lithic

3

though

many

of

its

general

features

were

preserved.

The

emphasis

of

Neolithic

3

flint

production

remained

the

manufacture

of

blade

tools

but

they

were usually

smaller

than

in

Neolithic

2.

Pyramidal

cores

were

now

preferred

which

yielded

shorter

blades

than

the

double-ended

cores

of

Neolithic

3.

Arrowheads

were

usually

smaller

though

in

Syria

and

Lebanon

several

types

of

very

large

arrowhead

continued

to

be

made

throughout Neolithic

3.

Short,

regular,

segmented

sickle

blades

hafted

in

composite

sickles

were

now

used

rather

than

the

large

blades

of

Neolithic

2.

These

segmented

sickle

blades

had

a

serrated

or

denticulated

cutting

edge

and

cut

most

effectively

when

the

sickle

was

used with

a

sawing

motion.

A

new

feature

of

the

flint

industry

on

some

Neolithic

3

sites

was

the

manufacture

of

large

axes,

adzes,

picks

and

other

heavy

flaked

tools.

These

tools

were

apparently

developed

to

cut

timber

and

prepare

land

in

areas

which

had

not

previously

been

favoured

for

permanent

settlement.

The

principal

cultural

innovation

in

Neolithic

3

was the

making

of

pottery,

Pottery

was

first

used

on sites

in

Syria

and

Lebanon

about

6000

B.C.

At

the

beginning

it

was made

in

small

quantities

but

the

craft

flourished

so

that

soon

after

its

introduction pottery

became

an

item

of

every

day

use

throughout

-

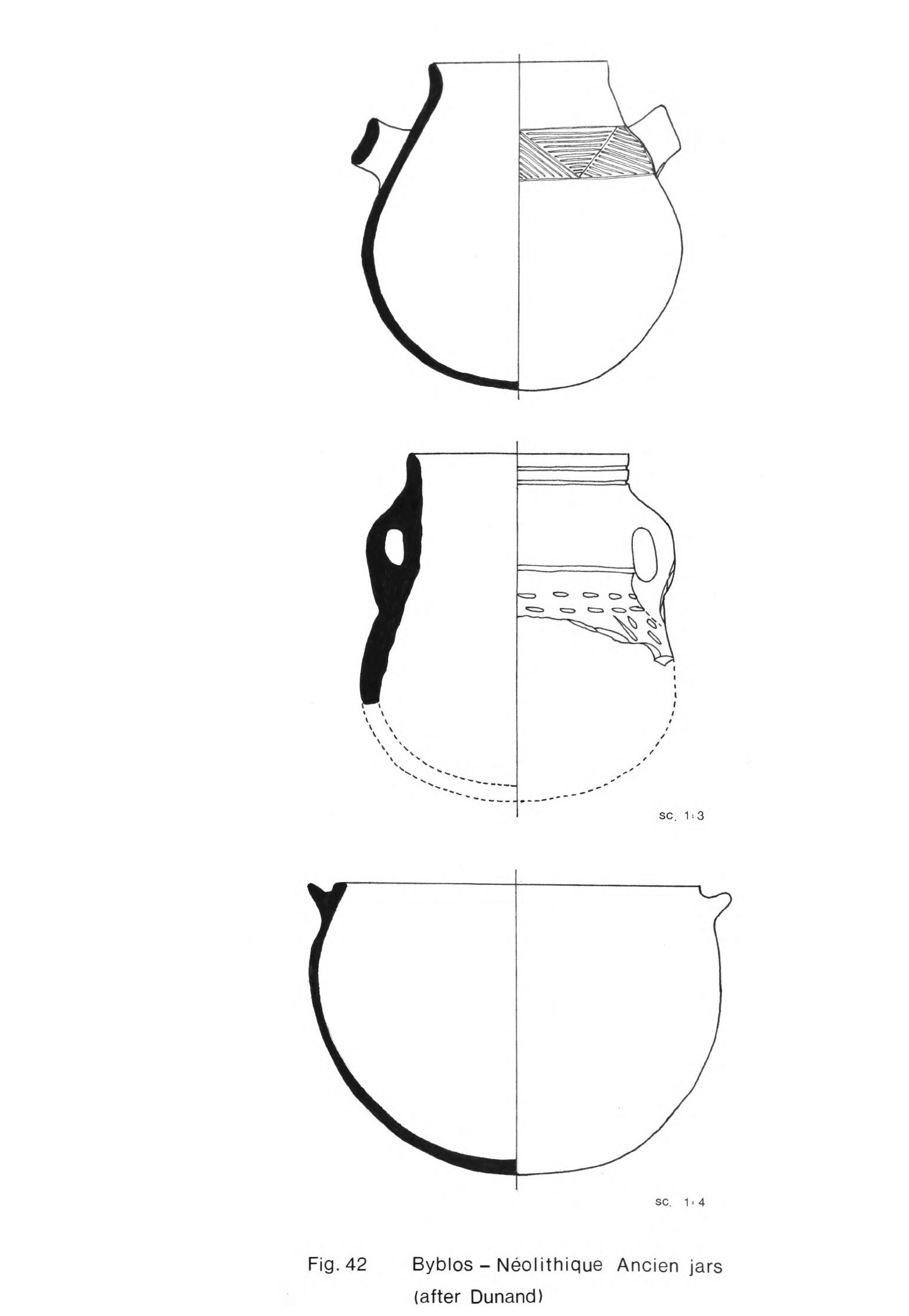

295

-

the

central

and

northern

Levant

although

pottery

was not

used

in

the

southern

Levant

until

several

centuries

later.

From

the

outset there

was

much

variety

in

fabric

and

decoration.

Pottery

is

such

a

conspicuous

item

in

the

archaeo-

logical

record

that

its

introduction

is

the

principal indicator

of

innovations

in

material

culture.

Other

important

changes

were

taking

place

in

economy

and

the

pattern

of

settlement

at

the

time

that

pottery

was introduced. These

changes

in

artifacts

and

way

of

life

are

the

main

evidence

that

a

new

stage

of

the

Neolithic

was

developing.

Pottery

is

the

most

easily

recognisable

new

artifact

and

for

this

reason

the

moment

when

its

manufacture

began

is

the

most

convenient

point

at

which

to

date

the

beginning

of

Neolithic

3.

Although

the

introduction

of

pottery

was

such

a

striking

innovation

the

changes

in

the

buildings

and

flint

industry

were

simply

a

modification

of

the

Neolithic

2

tradition.

In

general

there

was

cultural

continuity

from

Neolithic

2

to

Neolithic

3

in

the

Levant,

evidence

for

which

has

been

found

at

Abu

Hureyra,

Buqras,

Ras

Shamra,

Tell

Ramad

and

Tell

Labweh.

In

Palestine

the

Neolithic

2

pattern

of

existence

was

disrupted

and

the

Neolithic

3

way

of life

there,

when

finally

established,

was

somewhat

different

from

further

north.

The

Neolithic

3

economy

differed

in

several

ways

from

that

of

Neolithic

2

though

it

developed

from

it.

There

was

a

stronger

emphasis

on

agriculture

in

the

villages

of

Neolithic

3

than

in

Neolithic

2.

Herding

grew

markedly

in

importance

on

some

sites

while

hunting

and

the

gathering

of

wild

plants

contributed

less

to

the

diet

of

the

settled population

than

before.

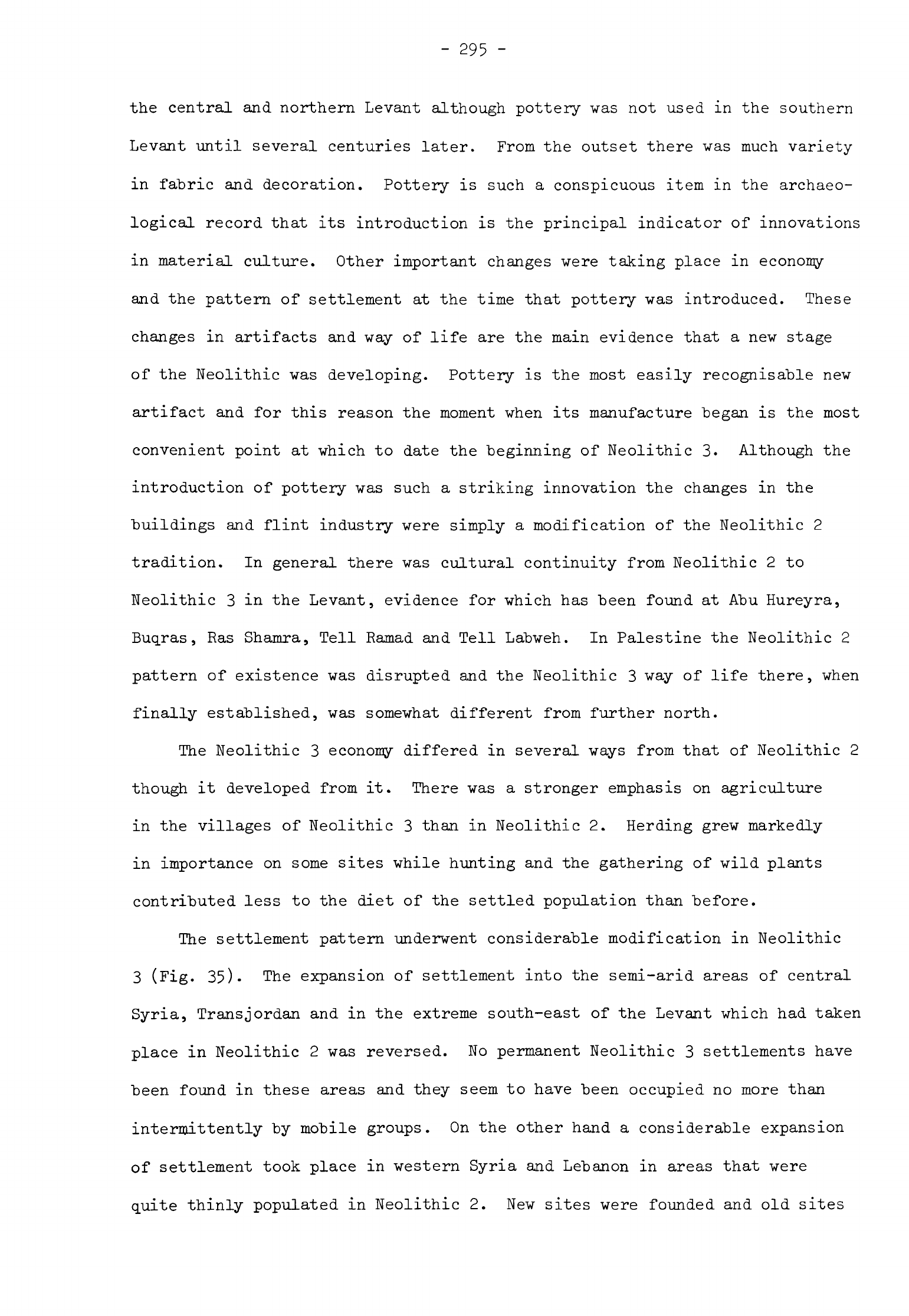

The

settlement

pattern

underwent

considerable

modification

in

Neolithic

3

(Fig.

35)-

The

expansion

of

settlement

into

the

semi-arid

areas of

central

Syria,

TransJordan

and

in

the

extreme

south-east

of

the

Levant

which

had

taken

place

in

Neolithic

2

was

reversed.

No

permanent

Neolithic

3

settlements

have

been

found

in

these

areas

and

they

seem

to

have

been

occupied

no more than

intermittently

by

mobile

groups.

On the

other

hand

a

considerable

expansion

of

settlement

took

place

in

western

Syria

and

Lebanon

in

areas

that

were

quite

thinly

populated

in

Neolithic

2.

New

sites

were

founded

and

old

sites

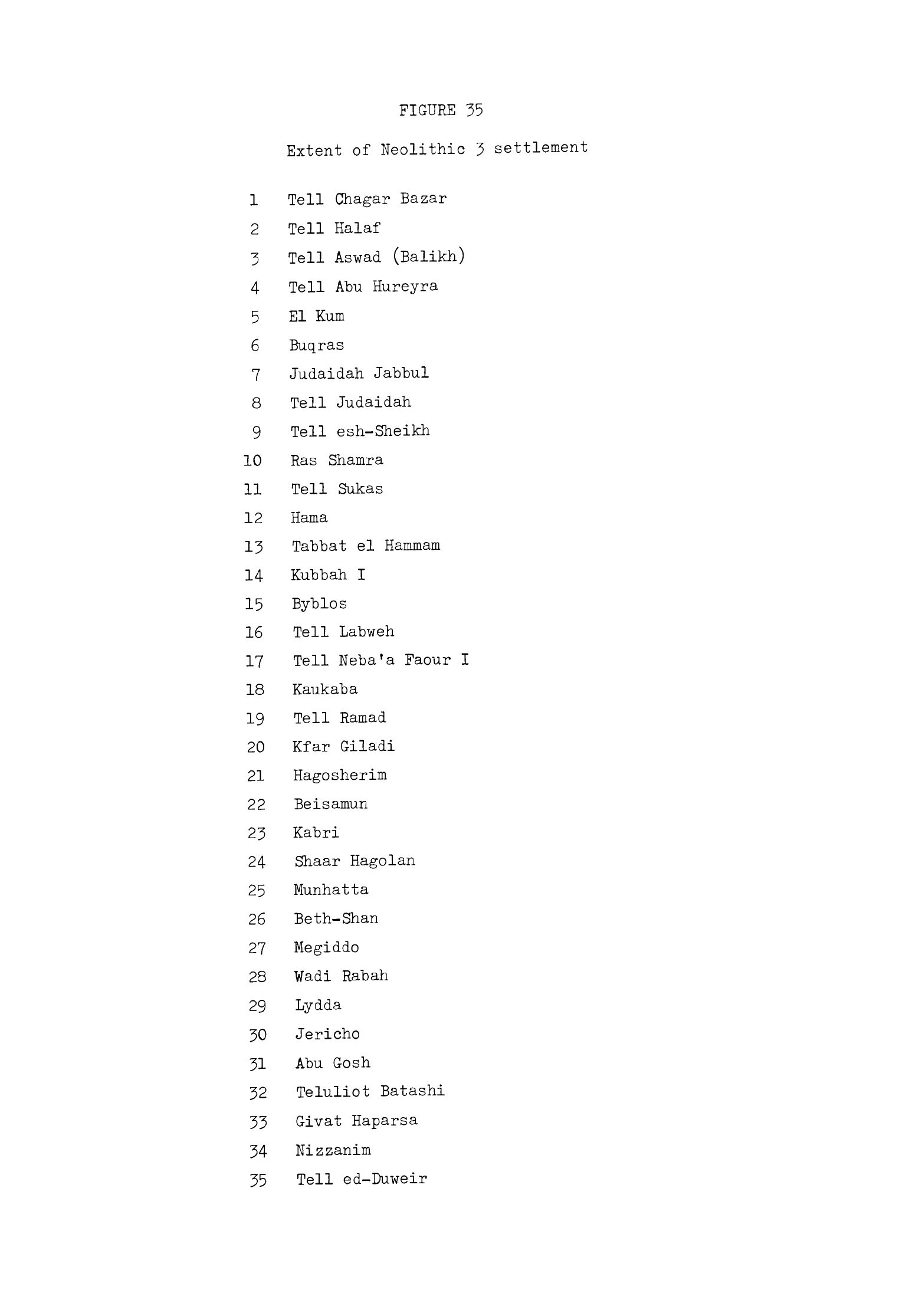

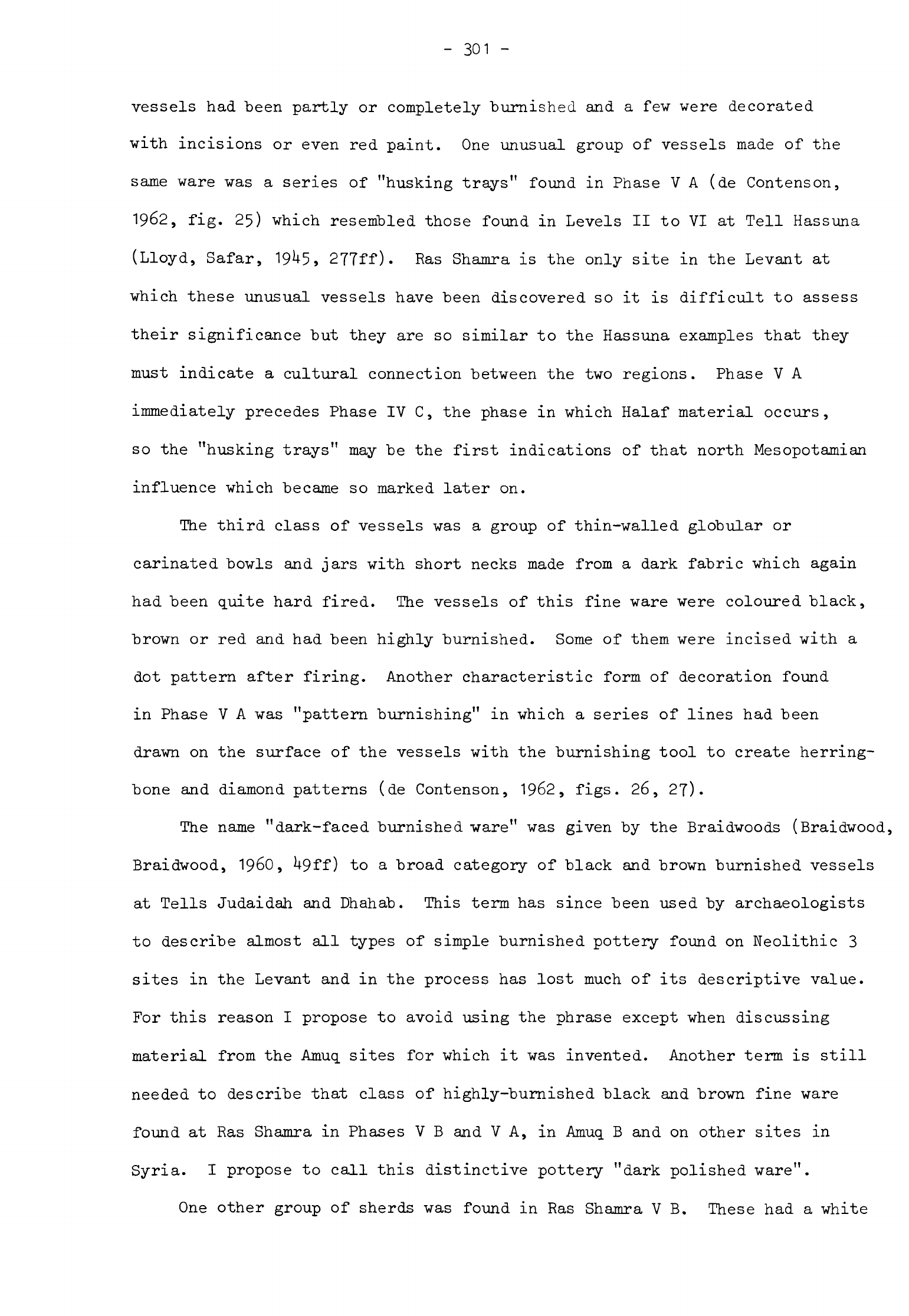

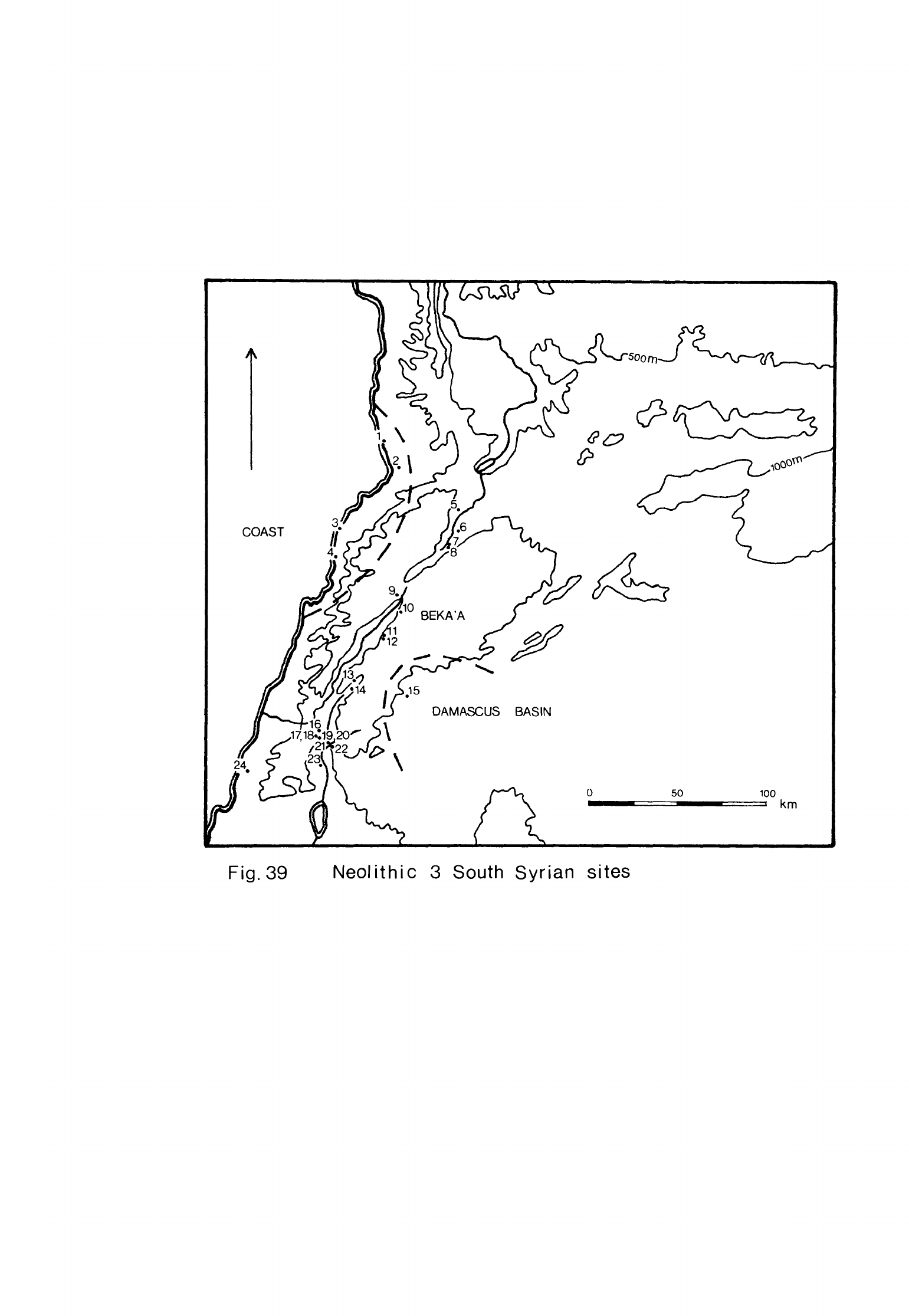

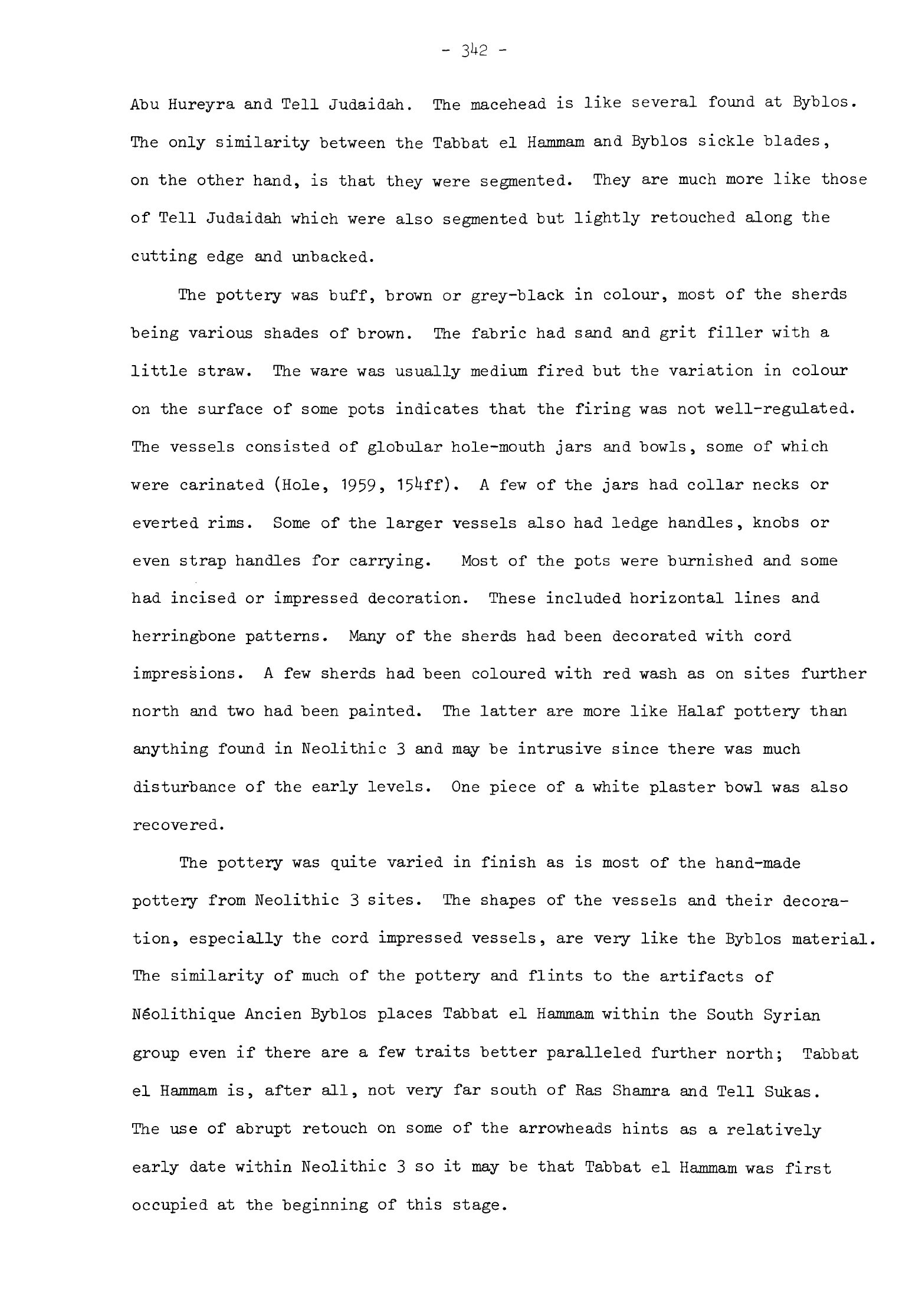

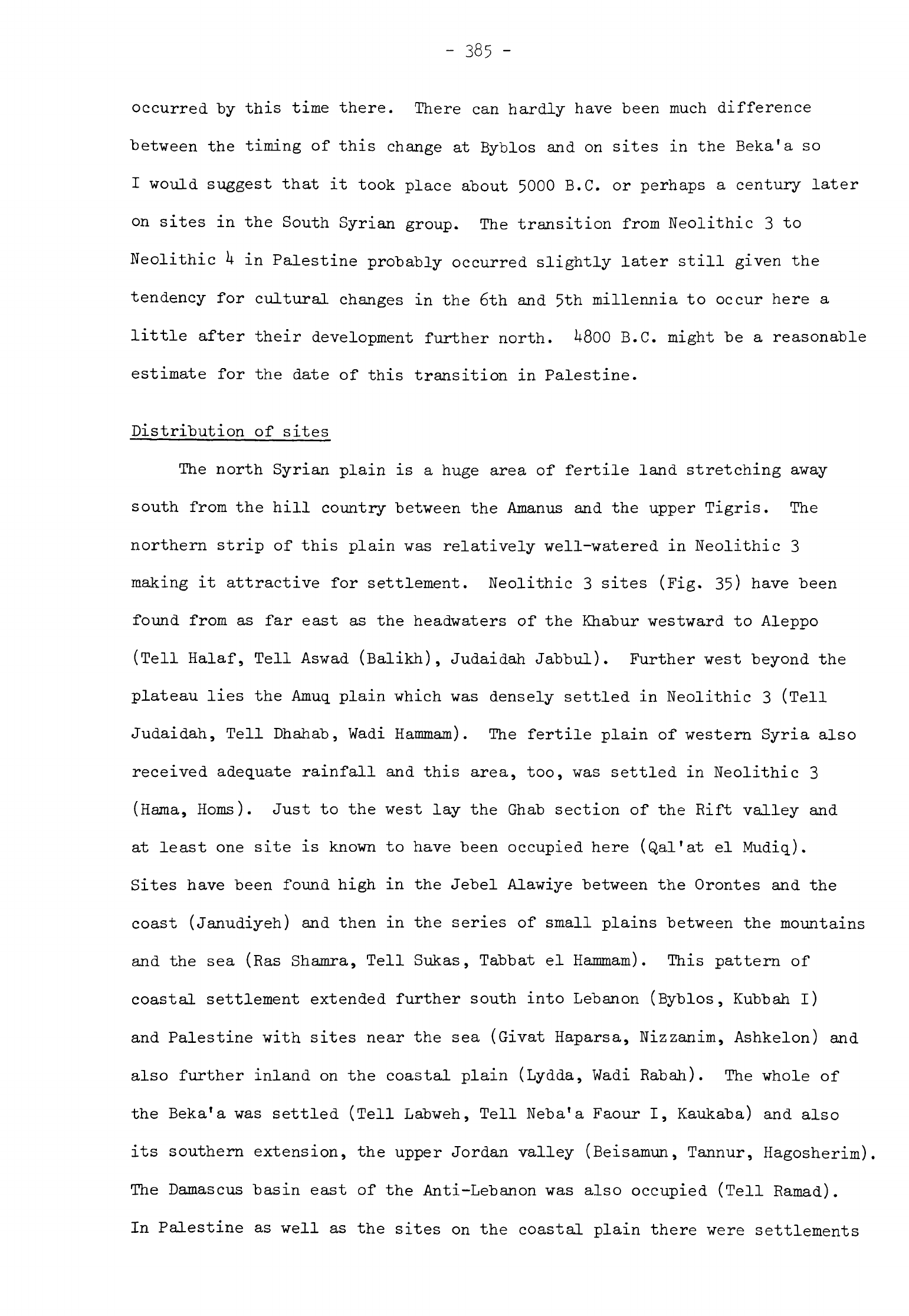

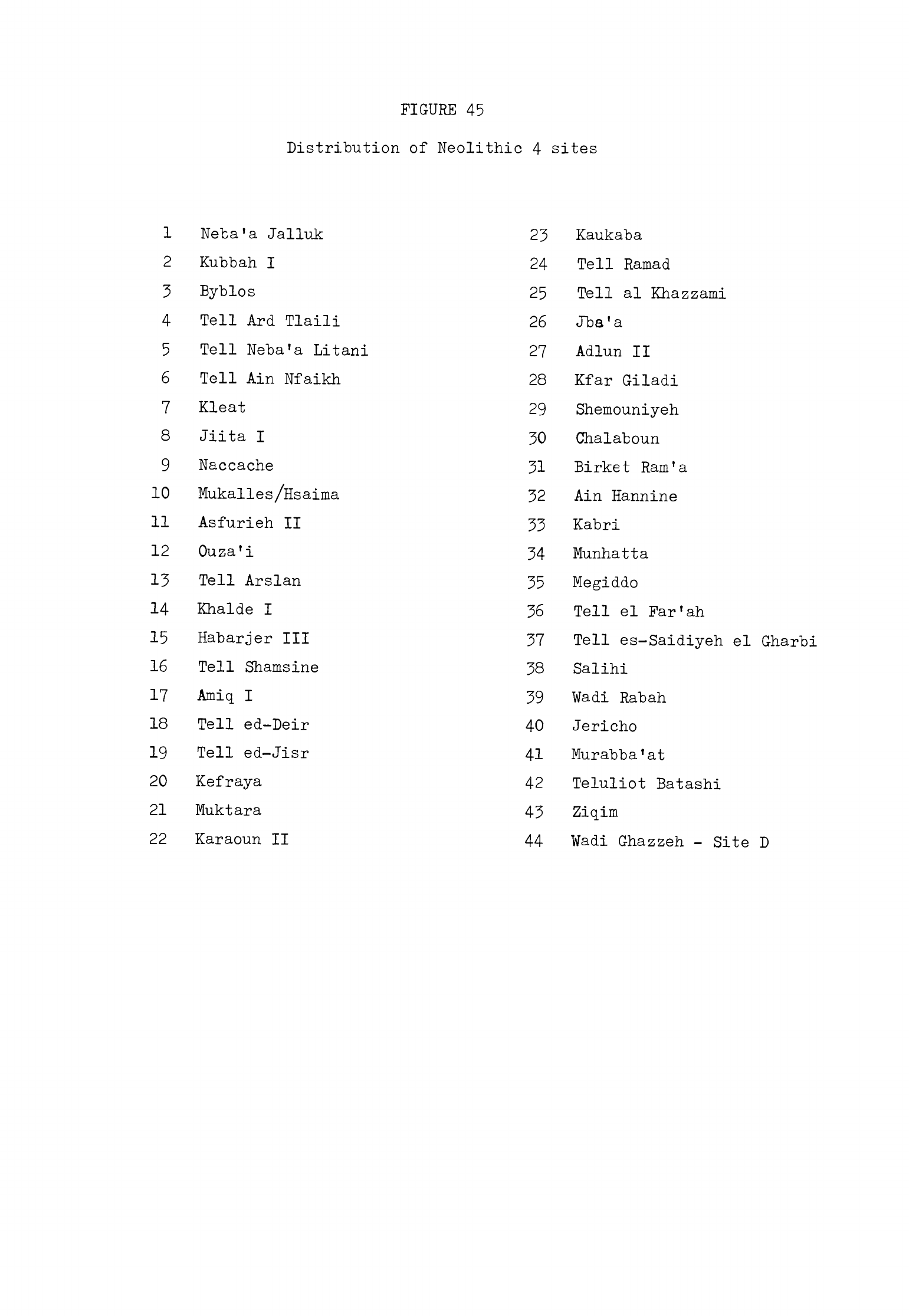

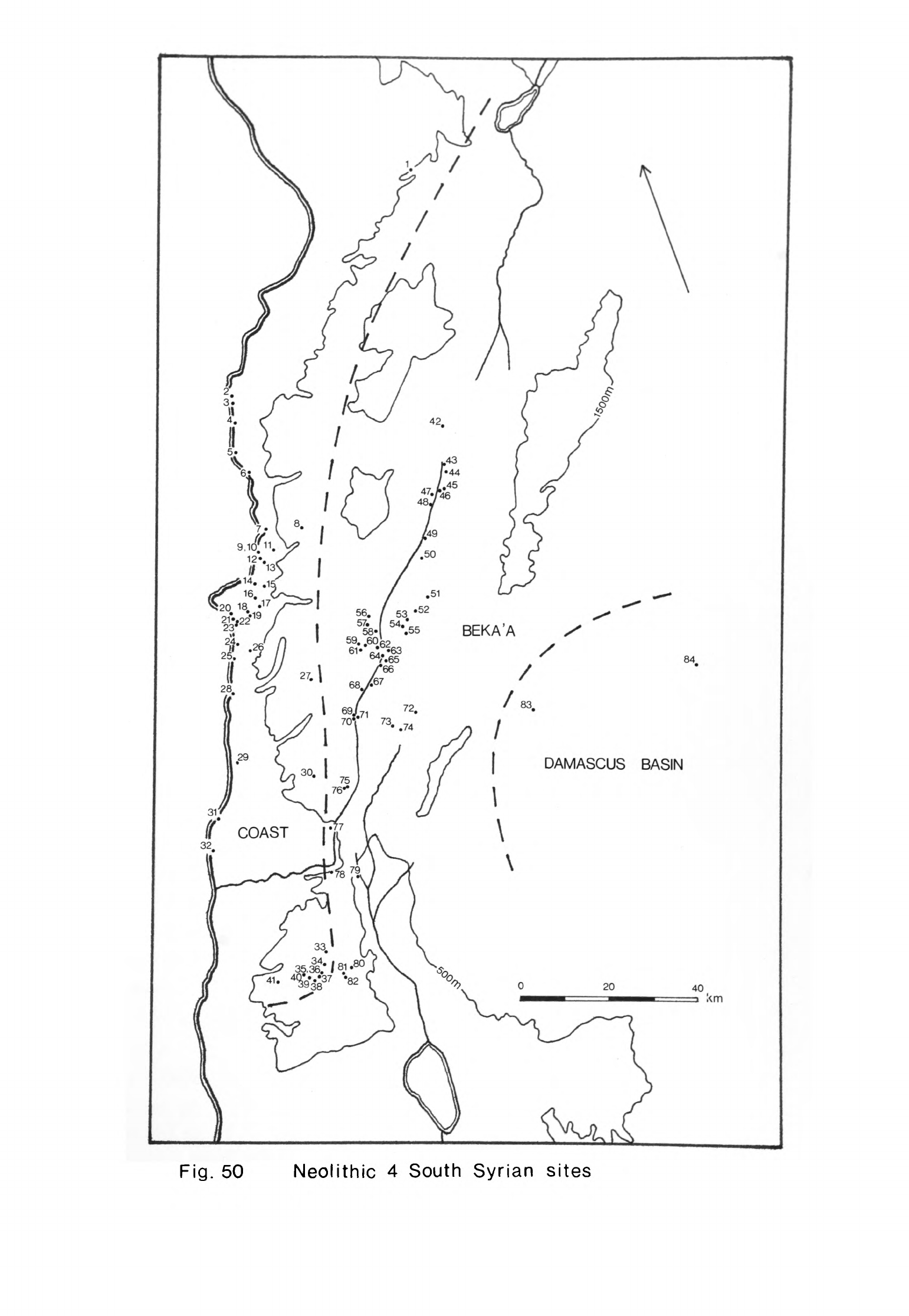

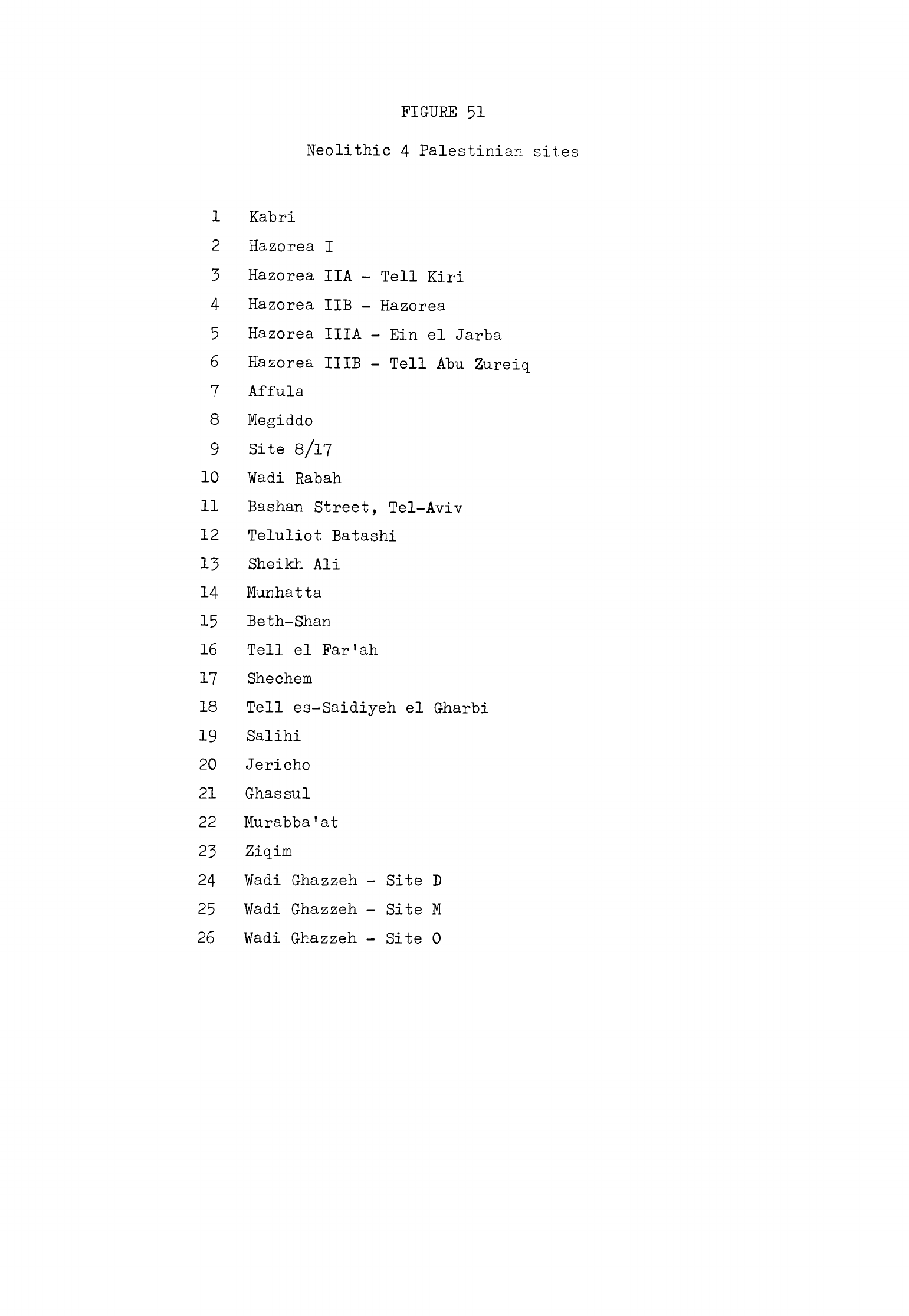

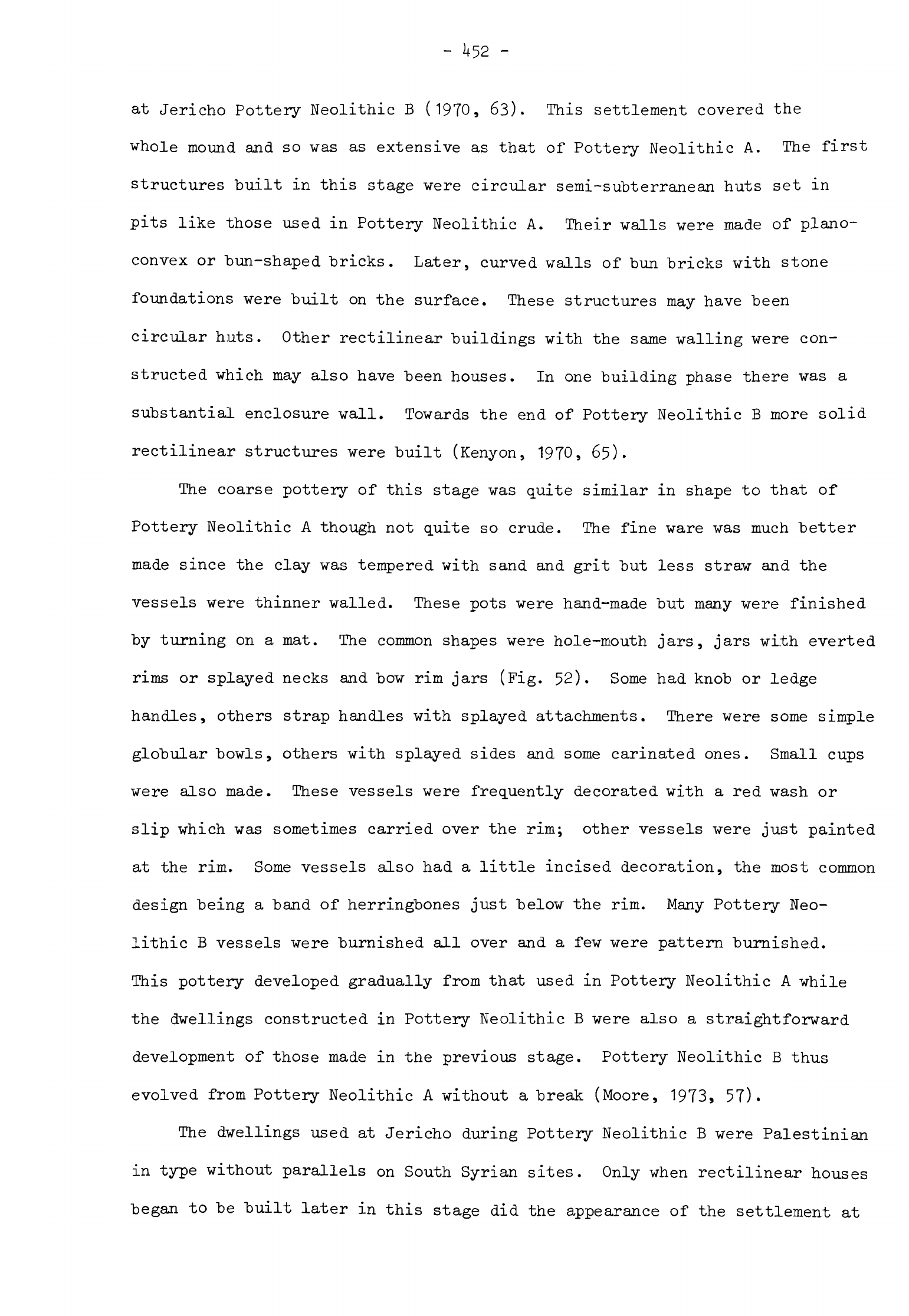

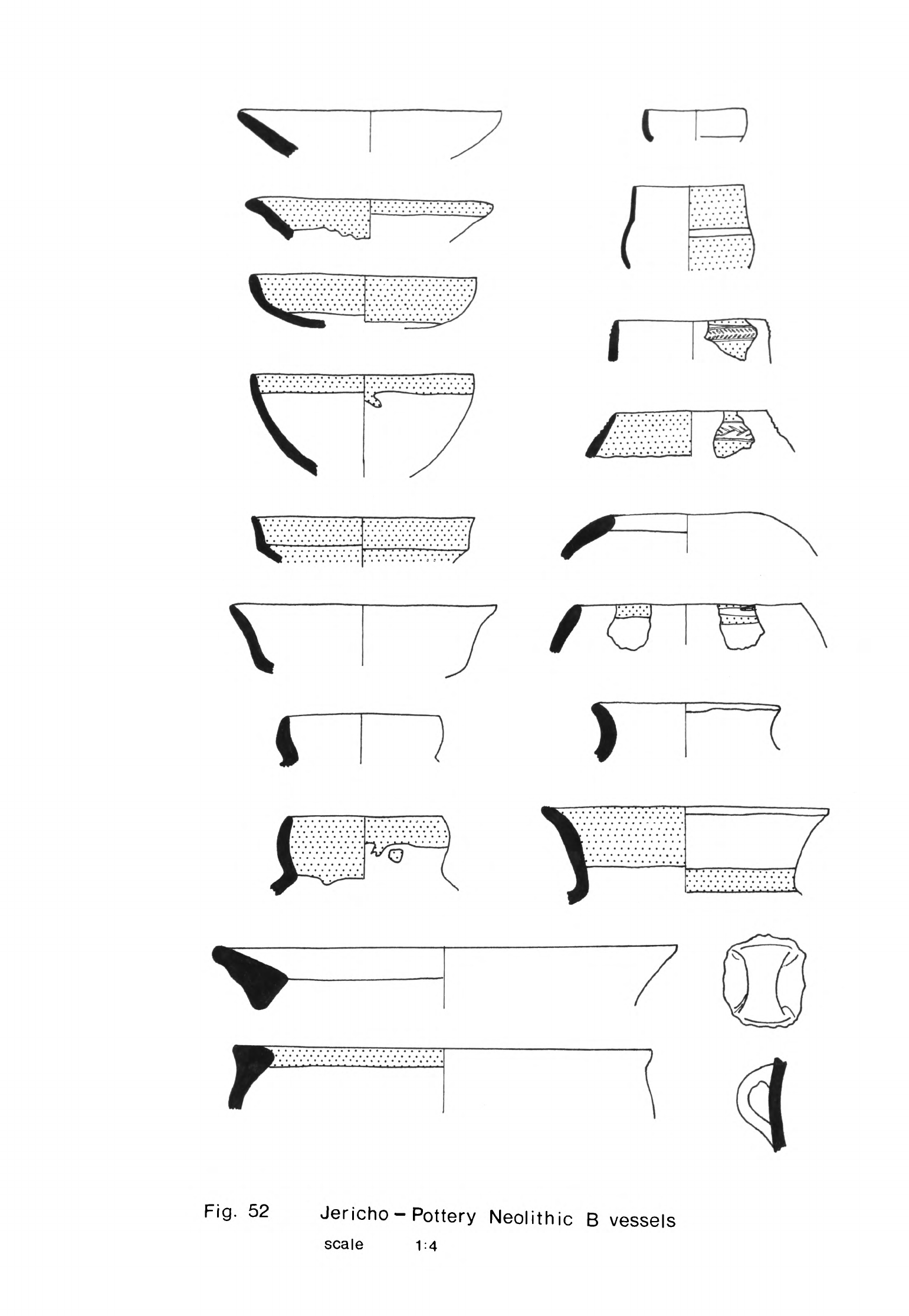

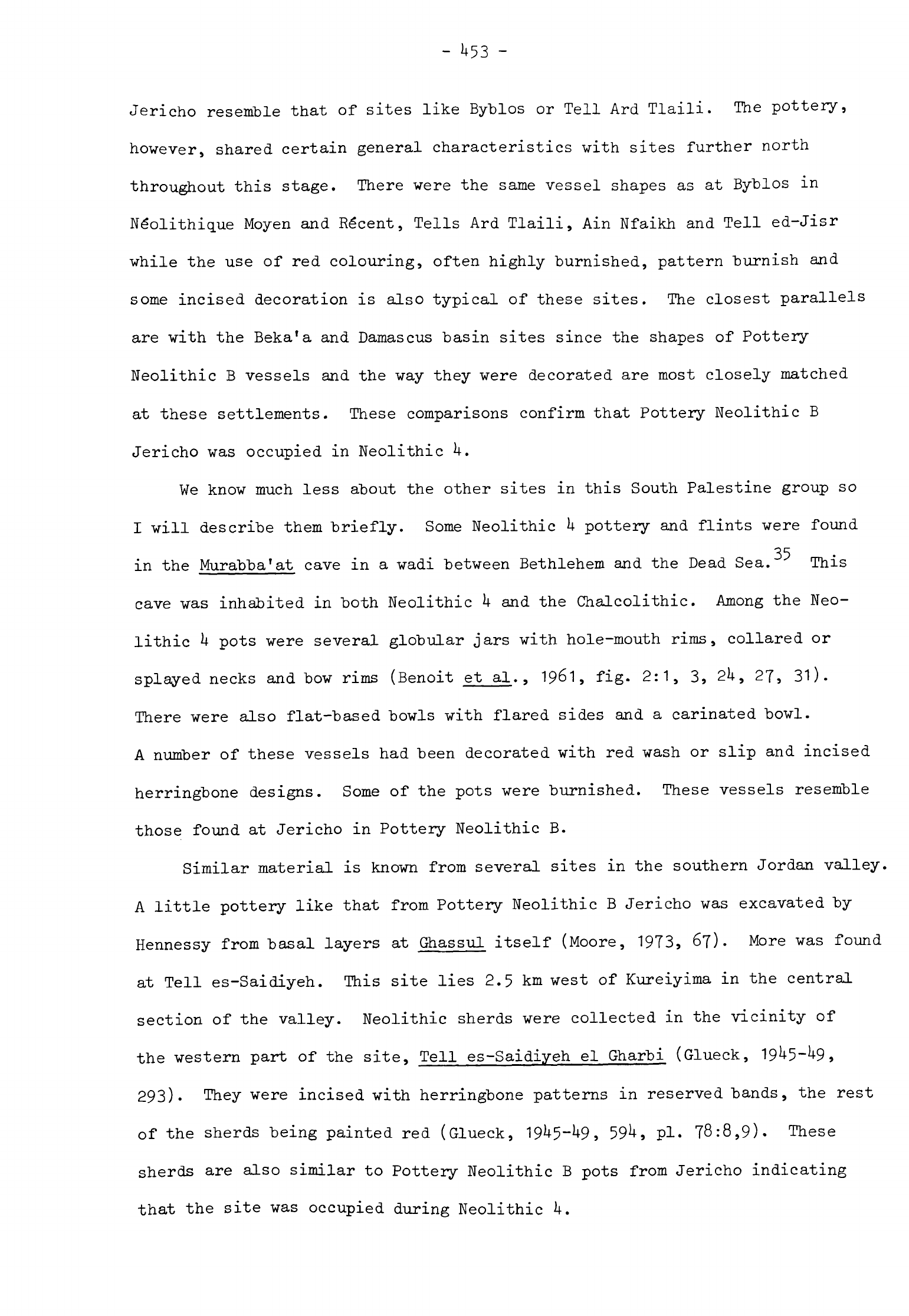

Fig.35

Extent

of

Neolithic

3

settlement

A

sites

abandoned

early

in

Neolithic

3

scale

1

=

4,000,000

FIGURE

35

Extent

of

Neolithic

3

settlement

1

Tell

Chagar

Bazar

2

Tell

Halaf

3

Tell

Aswad

(Balikh)

4

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

5

El

Kum

6

Buqras

7

Judaidah

Jabbul

8

Tell

Judaidah

9

Tell

esh-Sheikh

10

Ras

Shamra

11

Tell Sukas

12

Hama

13

Tabbat

el

Hanunam

14

Kubbah

I

15

Byblos

16

Tell

Labweh

17

Tell

Neba'a

Faour

I

18

Kaukaba

19

Tell

Ramad

20

Kfar

Giladi

21

Hagosherim

22

Beisamun

23

Kabri

24

Shaar

Hagolan

25

Munhatta

26

Beth-Shan

27

Megiddo

28

Vadi

Rabah

29

Lydda

30

Jericho

31

Abu

Gosh

32

Teluliot

Batashi

33

Givat

Haparsa

34

Nizzanim

35

Tell

ed-Duweir

-

296

-

enlarged

along

the

Syrian

and

Lebanese

coasts

and

in

the

Beka'a

and

Orontes

valleys.

There

was

also

settlement

expansion

in

the

Amuq

basin

and

north-

west

Syria

to

the

west

of the Euphrates.

In

Palestine

the

old

settlement

pattern

was

considerably

disturbed.

Most

Neolithic

2

sites

were

abandoned

then

new

sites

were

founded

later

in

slightly

different positions.

The

population

of

the

Negev

and Sinai was

much

reduced

although

there

are

indications

that

these

areas

continued

to

be

inhabited.

Having

briefly

mentioned

the

most

important

developments

that

took

place

in

Neolithic

3 I

shall

now

consider

the

archaeological

evidence

in

detail

taking

each

region

in

turn.

Middle

Euphrates

The

principal Neolithic

2

settlement

sites

along the

Middle

Euphrates

were

abandoned

in

Neolithic

3.

Permanent

occupation

at

Mureybat

ceased

at

the

end

of

phase

IV

sometime

in

Neolithic

2

and

although

there

are

indications

that

the

site

was

used

in

later

periods,

even

possibly

in

Neolithic

3»

it

was

never

subsequently inhabited

as

a

permanent

settlement.

Abu

Hureyra

continued

to

be

occupied

until

early

in

Neolithic

3

so

that

here

one

can

trace

the

development

of

some

of

the

features

of

the

new

stage.

In

the

ceramic

Neolithic

phase

of

occupation

there

were

some

changes

in

the

structures

used

at

the

site

as

we

have

seen.

Shallow

pits

were

dug

between

the

buildings

which

continued

to

be

built

of

mud-brick

on

a

rectilinear

plan.

The

settlement

itself

shrank until

it

covered

only

half

the

area

of

the

aceramic

site.

There

were

slight

changes

in

the

flint

industry,

the

most

noticeable

being

an

increase

in

the

amount

of

retouch

by

squamous

pressure-

flaking

on

arrowheads

and

a

few

other

tools. The

other

artifacts

were

as

varied

as

they

had

been

in

the

later

ceramic

phase,

the

one

innovation

being

the

introduction

of

pottery.

This

and

the

other

new

features

found

in

the

excavation

were

sufficient

to

mark

a

new

phase

of

occupation,

the

ceramic

Neolithic,

even

if

it

was

obviously

a

continuation

of

the

later

aceramic

-

297

-

Neolithic

settlement.

The

appearance

of

pottery,

albeit

in

modest

amounts,

the

changes

in

the

flint

industry

and

the

digging

of

large

pits

around

the

mud-brick

"buildings

are

all

hallmarks

of

Neolithic

3

so

that

the

ceramic

Neolithic

phase

of

occupation

at

Abu

Hureyra

can

be

ascribed

to

this

stage.

The

remains

of

the

Neolithic

3

settlement

at

Abu

Hureyra

had

suffered

considerably

from

weathering

and

much

of

the

deposit

had

simply

been

eroded

away.

For

this

reason

it

is

difficult

to

know

exactly

when

the

settlement

was

abandoned

but

from

the

typology

of

the

artifacts

it

would

appear

that

occupation

ceased

about

the

same

time

as

at

Buqras,

that

is

early

in

the 6th

millennium.

Tell

Kreyn

near

Abu

Hureyra

was

certainly

occupied

in

Neolithic

2

and

again

in

the

Halaf.

The

foci

of these two

settlements

were

several

tens

of

metres

apart

and there

were

no

surface

indications

of

material

that

would

fill

the gap

between

the

two

phases

of

occupation,

a

gap that

corresponds

to

Neolithic

3.

The

inference

to

be

drawn

from

this,

admittedly

inconclusive,

evidence

is

that

the

site

was

abandoned

during

the 6th

millennium.

The

level

III

occupation

at

Buqras

also

falls

in

Neolithic

3

on

the

evidence

of

the

few

potsherds

that

were

found

in

the

deposit.

The

other

artifacts

were

similar

in

type

to

those

of

levels

II

and

I.

The

structures

in

level

III

consisted

of

mud-brick

walls

as

in

the

earlier

levels.

The

sequence

at

Buqras was

continuous

and

occupation

at

the

site

came

to

an

end

about

5900

B.C.,

as

we

have already

noted.

Abu

Hureyra,

Kreyn

and

Buqras

all

seem

to have

been

abandoned

in

the

first

half

of

the

6th

millennium

and

Mureybat

perhaps

a

little

earlier.

In

itself

such

a

break

in

the

occupation

of

sites

along

the

Euphrates

need

not

have

been

significant

since

few

excavated

Neolithic

sites

have

proved

to

be

continuously

occupied

for

more

than

several

centuries

at

a

time.

Each

may

have

been

abandoned

because

of

local

circumstances, perhaps

a

change

in

the

structure

of

the

settlement

or

the

local environment.

The

important

fact

to

note

is

that

once

these

sites

were

abandoned

no

others

were founded

along

the

-

298

-

Middle

Euphrates

until

much

later.

This

observation

is

based

upon

inadequate

information

since

the

course

of

the

Middle

Euphrates

has

not

yet

been

fully

surveyed

but

in

the

areas

which

have

been

examined Neolithic

2

and

Halaf

settlements

have

been

found

but

none

that

could

be

attributed

to

Neolithic

3.

This

is

most

obvious

in

the

area

above

the

new

Euphrates

dam

at

Tabqa

where

80

km

of

the

river

valley

have

been

carefully

surveyed.

There

are

three

Halaf

sites

known

in

this

area,

Shams

ed-Din

which

has

recently

been

excavated,

the

gas

station

site

at

Mureybat

(van

Loon,

1967

5

12)

and

Kreyn.

No

Neolithic

3

sites

have

been located

in

this

area

except

for

the

ceramic

Neolithic

phase

at

Abu

Hureyra.

The

same

observation

holds

true

for the

Jebel

Abdul

Aziz.

We

have

seen

that

the

Japanese

survey

team

found

Neolithic

2

sites

in

this

area

but

nothing

that

could

be

attributed

to

Neolithic

3.

Similar

results

were

obtained

by

the

same

team

when

they

surveyed

the

area

around

Palmyra.

All

the

Neolithic

sites

they

found

could

be

attributed

to

Neolithic

2

and

none to

Neolithic

3.

One

site

in

this

region,

El

Kum,

was

occupied

in

Neolithic

3.

The

remains

of

the

ceramic

Neolithic

settlement

were

substantial

consisting

of

at

least

two

superimposed

layers of

buildings.

The artifacts,

too,

were

abundant but,

except

for the

pottery,

little

different

from

those

of

the

aceramic Neolithic

phase

of

occupation.

For

this

reason

I

believe

El

Kum

may

not

have

been

occupied

for

more

than

the

earlier

centuries

of

the

6th

millennium

but

until

further

excavations

are

carried

out

in

the

untested

deposits

at

the

site

we

shall

not

know

for

certain.

A

great

deal of

pottery

was

found

in

the

brief

excavations

at

El

Kum.

The

soft,

straw-tempered

fabric

of most of

the

sherds

and

the

few

with

grit

filler

can

be

matched

on

most

Neolithic

3

sites

in

Syria

and

Lebanon.

The

red

painted

and

burnished

sherds

are

more

unusual

since

these

are

uncommon

on

sites

further

west

at

this

early

date.

Some

of

the

sherds

from

Buqras,

however,

have

a

similar

finish,

an

interesting

parallel

which

is

supported

by

the

similarities

in

the

flint

industries

and

other

remains

at

these

two

sites.

-

299

-

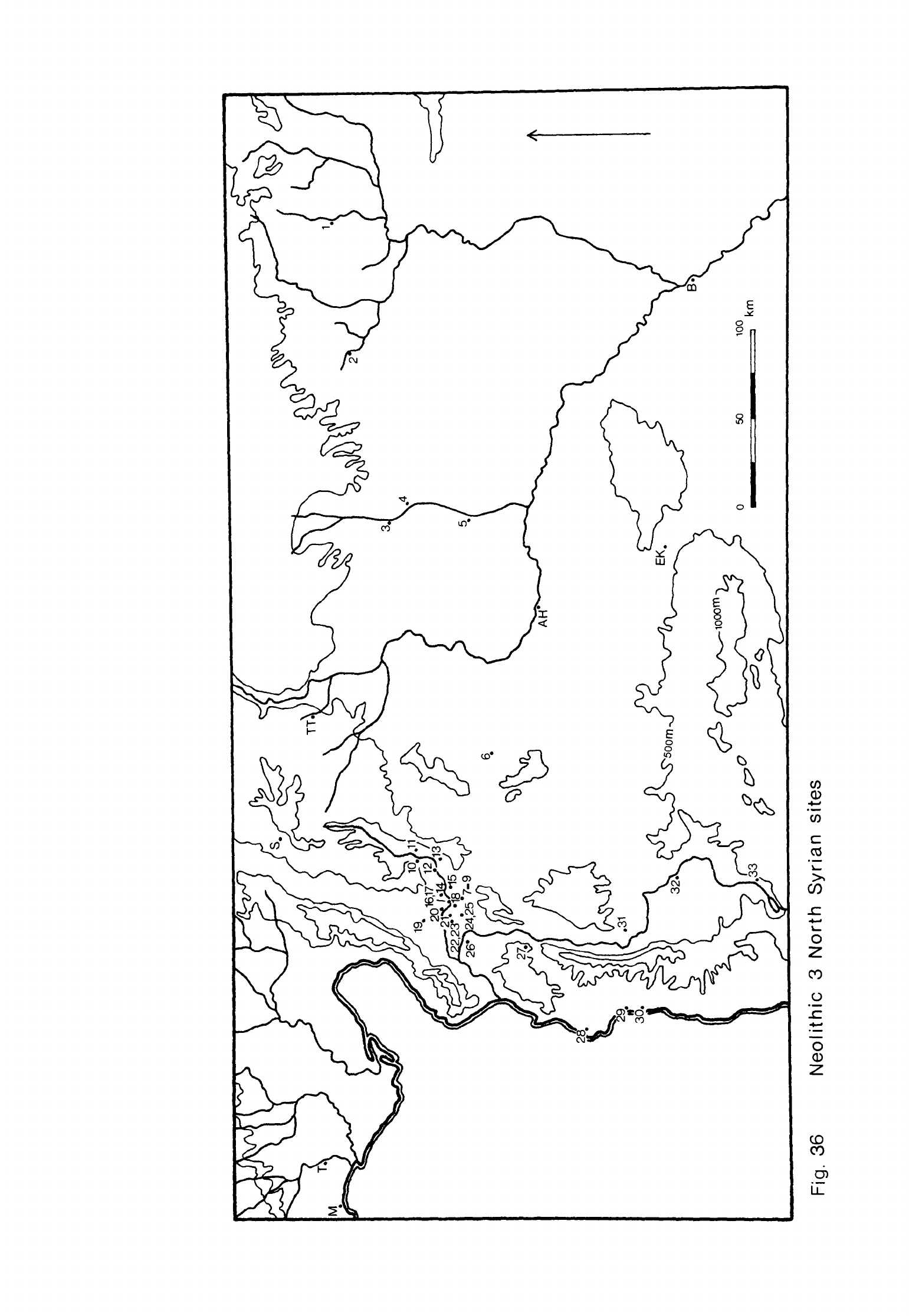

Having

considered

the

slight traces

of

Neolithic

3

settlement

in

the

Euphrates

region

I

will

now

turn

to

north-western

Syria where

many

Neolithic

3

sites

are

known

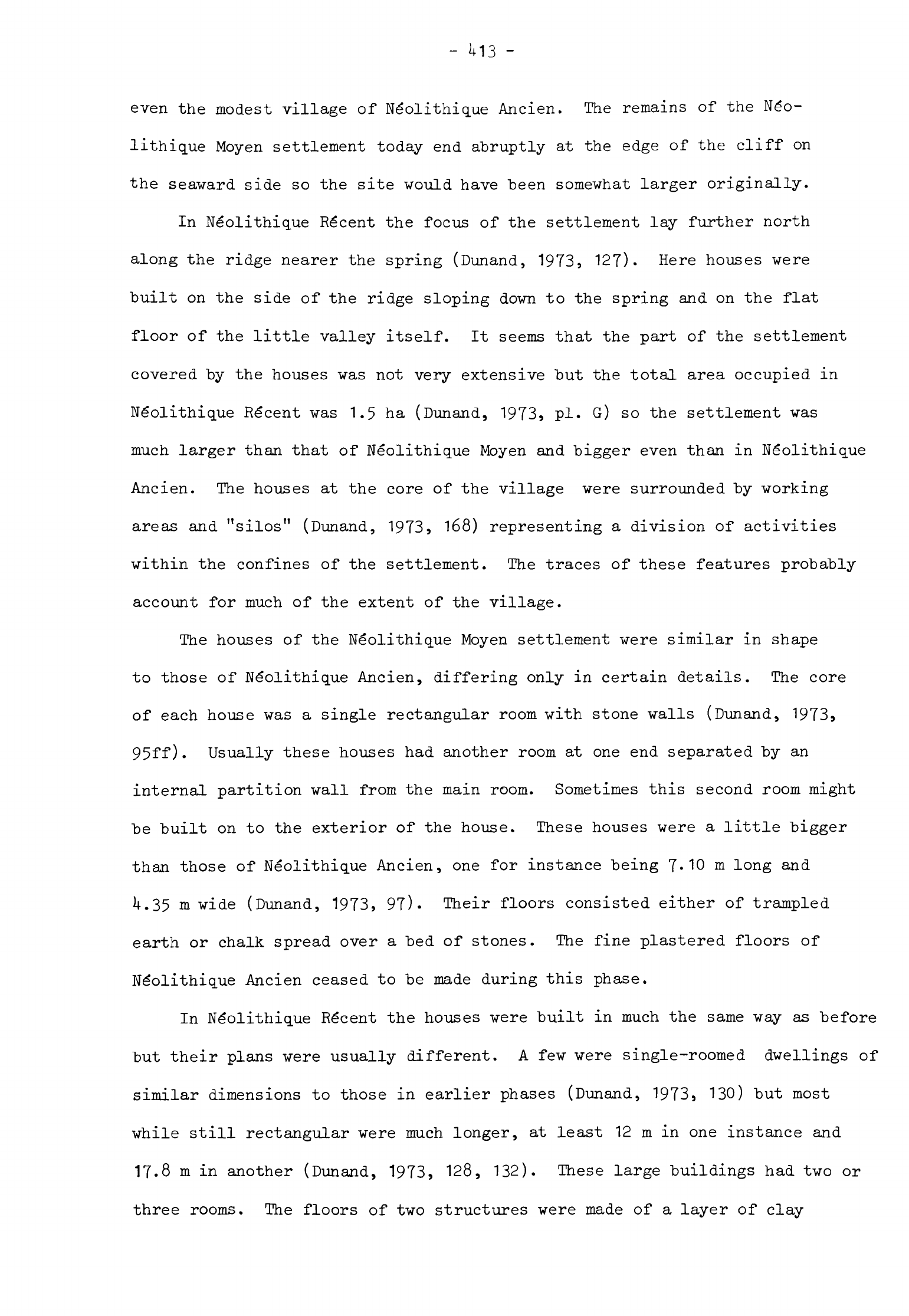

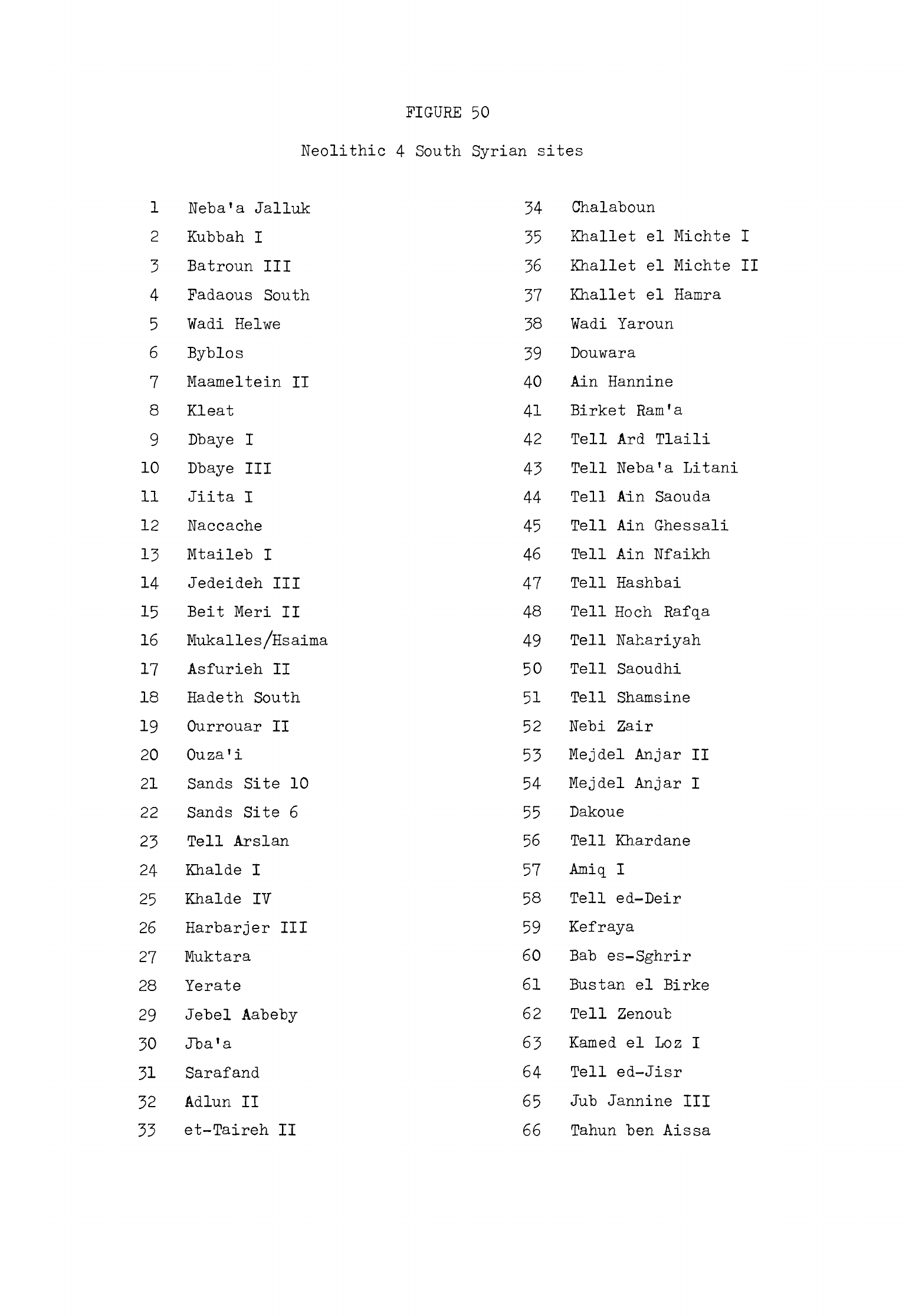

(Fig.

36)

and

describe

their

remains

in

turn.

North

Syria

Ras

Shamra

Ras

Shamra

was

occupied throughout Neolithic

3

and

its

deposits

provide

the

key

sequence

for

this

stage

in

north

Syria.

Remains

of

the

Neolithic

3

settlement have

been

found

in

the soundings

on

the

temple

acropolis

and

also

in

the

Palace

garden

(Schaeffer,

1962,

163)

so

it

appears to

have

"been

quite

as

extensive

as

the

Neolithic

2

site.

The

deposit

varied

from

2.6

to

3.3

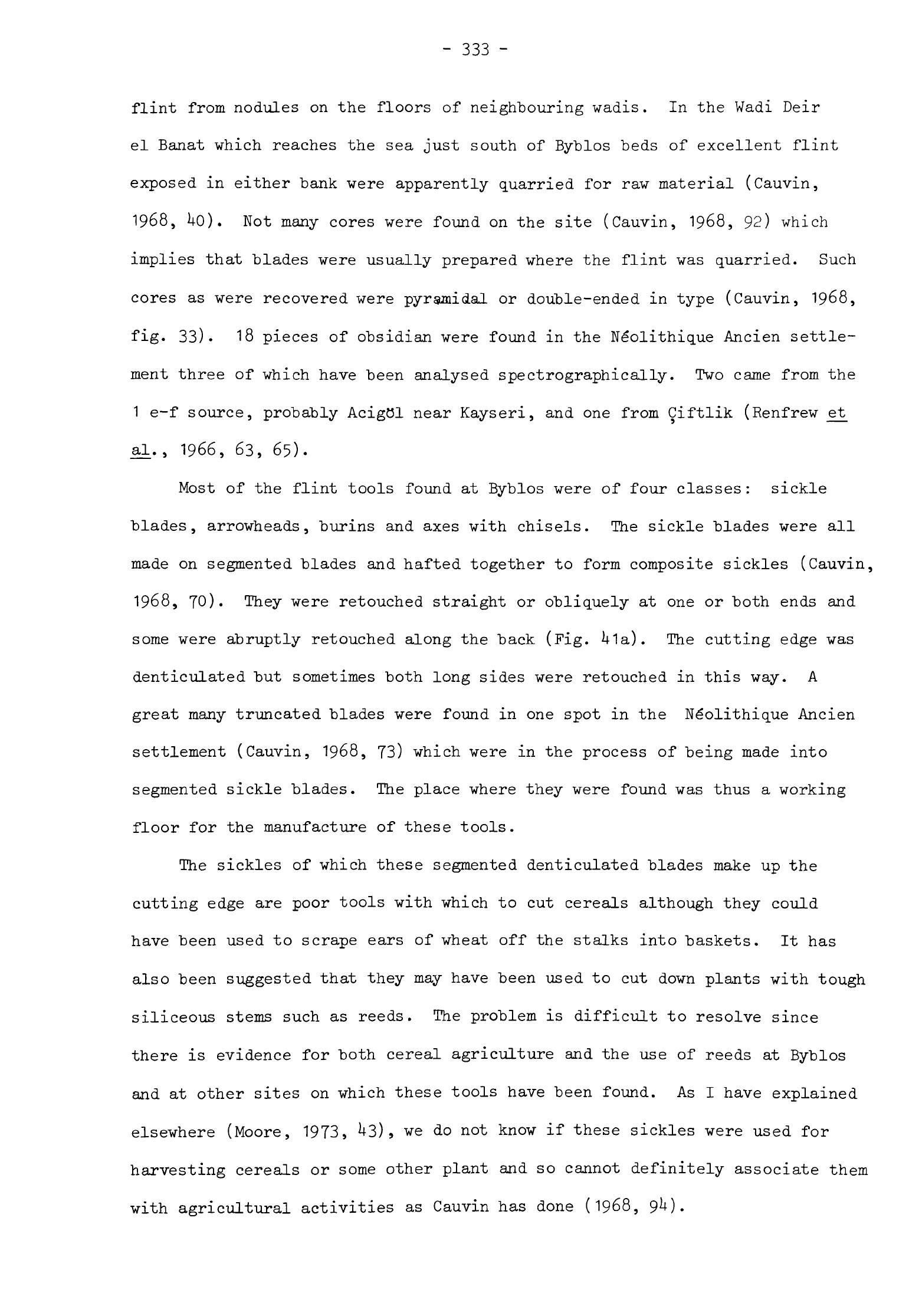

m

in

depth

and

has

been

divided

into

two

phases,

V

B or

Middle

Neolithic

(N<§olithique

Moyen)

and

V

A

or Late

Neolithic

(Neolithique

Recent).

The

houses

in

Phase

V

B

were

separated

from

each

other

and

had

a

single

rectangular

room

with

stone

walls

and

a

mud-brick

superstructure

(Kuschke,

1962,

260;

de

Contenson,

1963,

36).

Plaster

floors

were

associated

with

these

buildings

in

some

layers

(de

Contenson,

1962,

507)

and

other

trodden

earth

floors

were

quite

common.

A

clay-lined

pit

full

of

burned

earth,

charcoal

and

stones

was

also

excavated

in

these

layers

(de

Contenson,

1962,

509).

Much the

same

kind

of

rectilinear

structures

built

of

walls

with

stone

footings

were

found

in

Phase

V

A

(Kuschke,

1962,

259).

The

remains of

the

superstructure

of

one

of

these

buildings

was

found

in

one

area;

it

consisted

of

large

timbers

which

had

been

covered

with

vegetable

matter

and

clay

(de

Contenson,

1962,

505).

Many

floor surfaces

and

some

hearths

were

also

found

around

the

buildings

of

this

Phase.

These

features

were similar

to

the

domestic

structures

of

Phase

V

C

at

Ras

Shamra

so

there

was

no

change

in

the

building

tradition

here

between

Neolithic

2

and

3.

The

flint

tools

were

also

in

the

same

tradition

as

before

which,

it

should

be

remembered,

was

a

little

different

from

other

sites

in

Syria.

The

main

tool

types

were

pressure-flaked tanged

arrowheads

and

sickle

blades

with

finely-

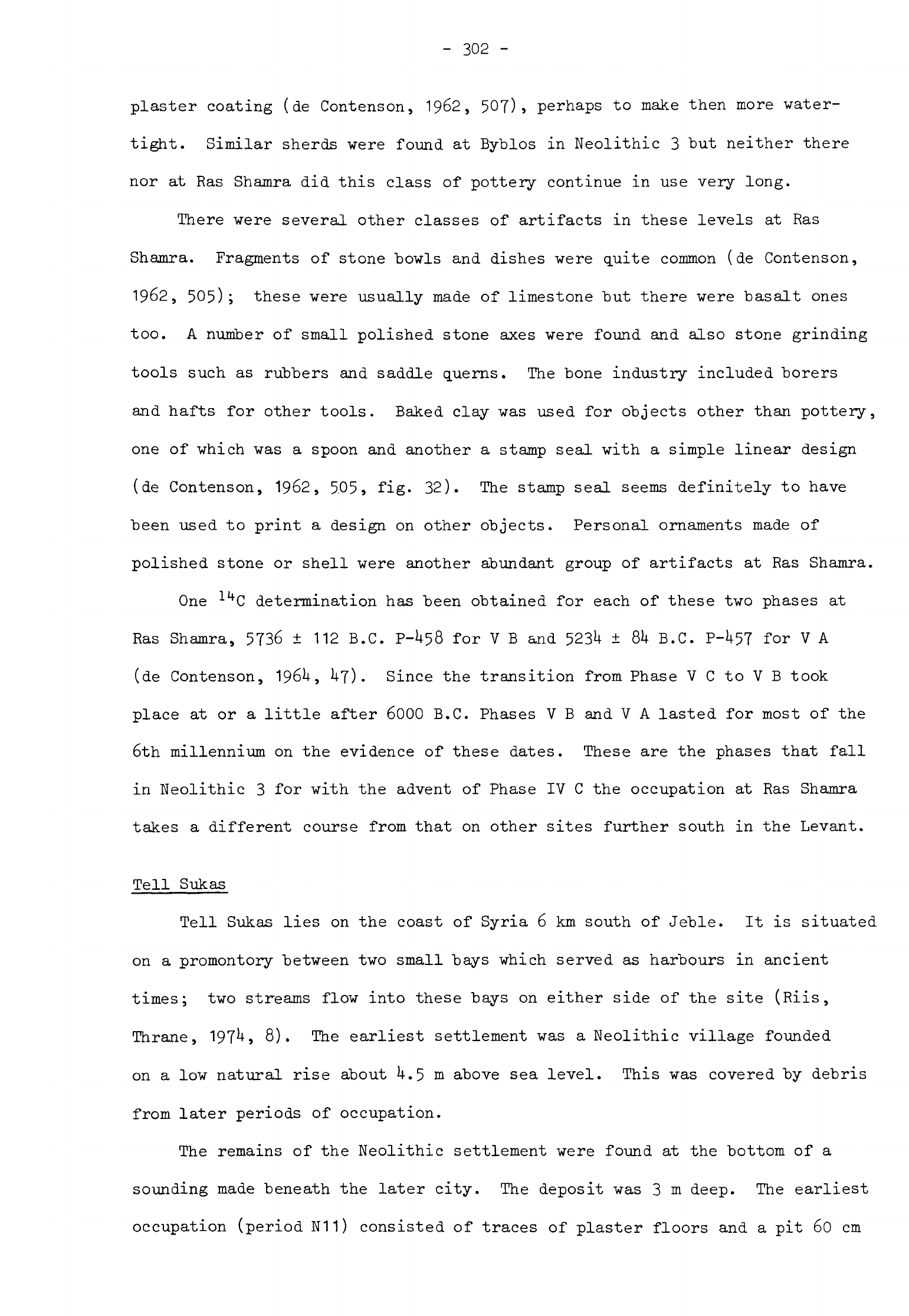

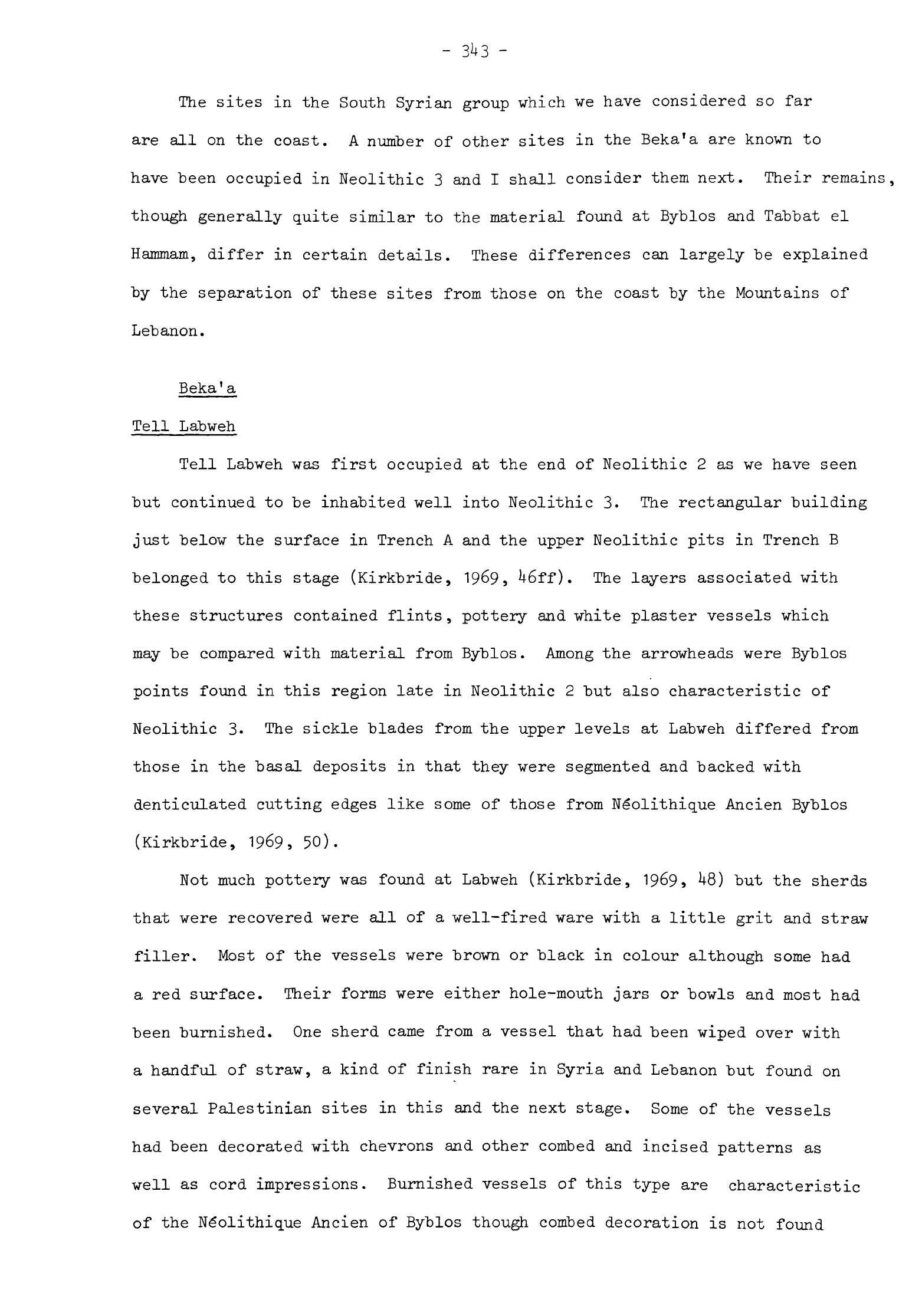

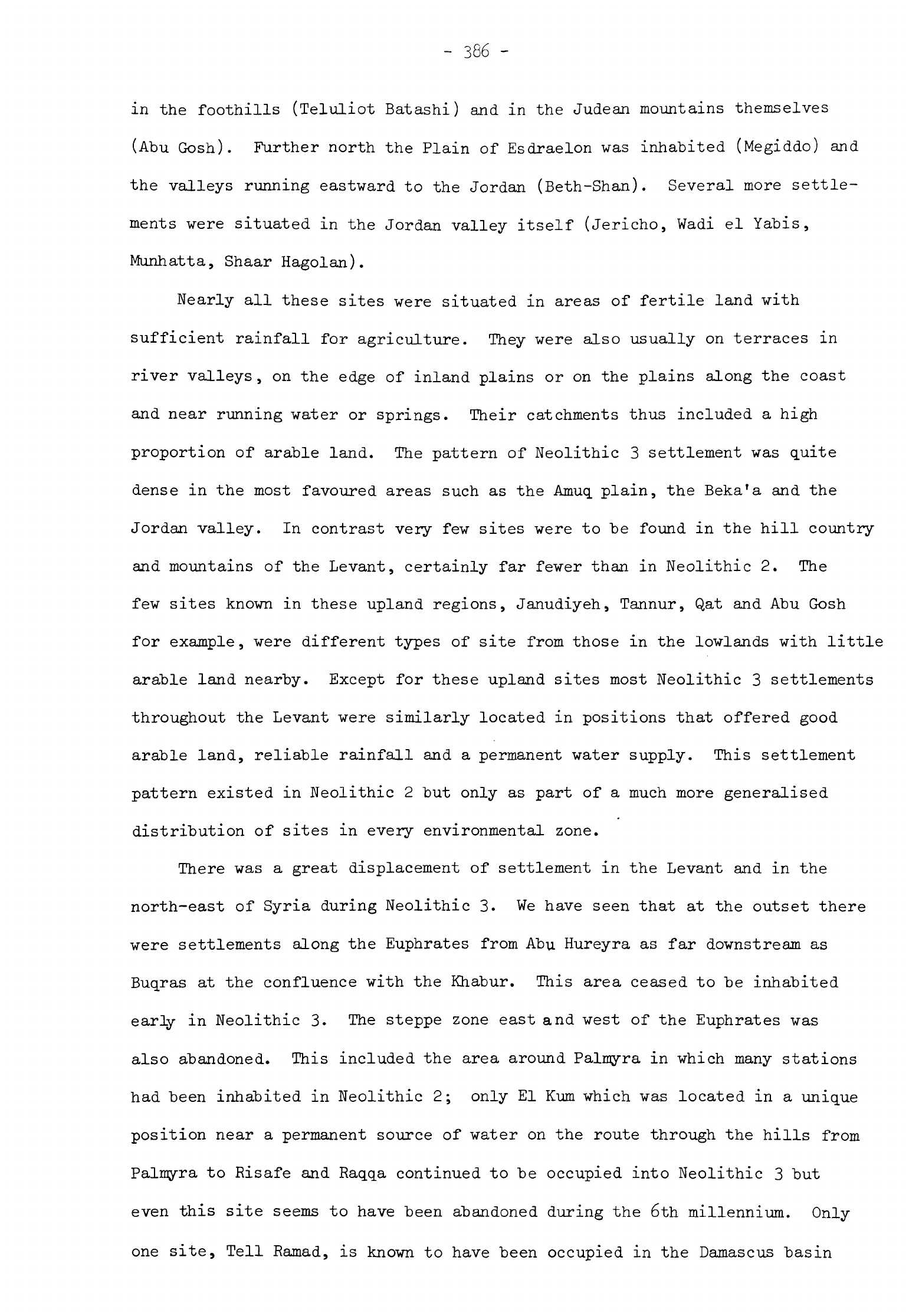

Fig.

36

Neolithic

3

North

Syrian

sites

FIGURE

36

Neolithic

3

North

Syrian

sites

1

Tell

Chagar

Bazar

2

Tell

Halaf

3

Tell

Hannnam

4

Tell

Aswad

(Balikh)

5

Tell

Khirbet

el

Bassal

6

Judaidah

Jabbul

7

Tell

Judaidah

8 Tell

Dhahab

9

¥adi

Hammam

10 Tell

Mahmutliye

11 Tell

Turundah

12

Tell

Faruq

13

Burj

Abdal

14

Gtfltepe

15

Tell

Davutpasa

16

Karaca

Khirbat

Ali

17

Tell

Qinanah

18

JJatal

Httylttk

19 Al

Kanisah

20

Myttktepe

21

Tell

Kurdu

22

Tell

Hasanusagi

23

Hasanusagi

al

Daiah

24

Qaddahiyyat

Ali

Bey

25

Tell

Karatas

26

Tell

esh-Sheikh

27

Janudiyeh

28

Ras

Shamra

29

Qal'at

er-Rus

30

Tell

Sukas

31

Qal'at

el

Mudiq

32

Kama

33

Horns

AH

Tell

Abu

Hureyra

B

Buqras

EK

El

Kum

M

Mersin

S

Sakcagflzu

1

T

Tarsus

TT

Tell

Turlu

-

300

-

denticulated

cutting

edges;

some

of

these

were

backed. Borers

and

scrapers,

including

at

least

one

fan

scraper

(de

Contenson,

1962,

505)

5

were

also

made.

Associated

with

these

tools

were

spherical

stone

hammers

which

may

have

been

used

in

flint

working

or

in

other

tasks.

A

little

obsidian

was

used

in

these

phases

but

from

which

sources

is

not

known.

The

flint

industry

gradually

"degenerated"

through

time,

to

use

de

Contenson's

phrase

(1962,

510)

which

means

that

fewer

of the

carefully-retouched

arrowheads

and

other

pressure-

flaked

tools

were

made.

This

is

an

indication

of

changing

needs

that

can

probably

be

linked

to

the

developments

which

were

taking

place

in

the

economy

of

the

site.

White plaster

ware

continued

to

be

made

in

the

lower

layers

of

Phase

V

B

(de

Contenson,

1962,

507)

"but

by

Phase

V

A

its

manufacture

had

been

discon-

tinued.

The

shapes

were

typical

of

those

found

on

Neolithic

2

sites

,

the

most

common

being

large

bowls

with

thick

walls

and

flat

or

hollow

bases.

The

surface

of

these

vessels

was

burnished

and

a

few

had

been

decorated

with

red

paint.

The

most

important cultural change

in

these

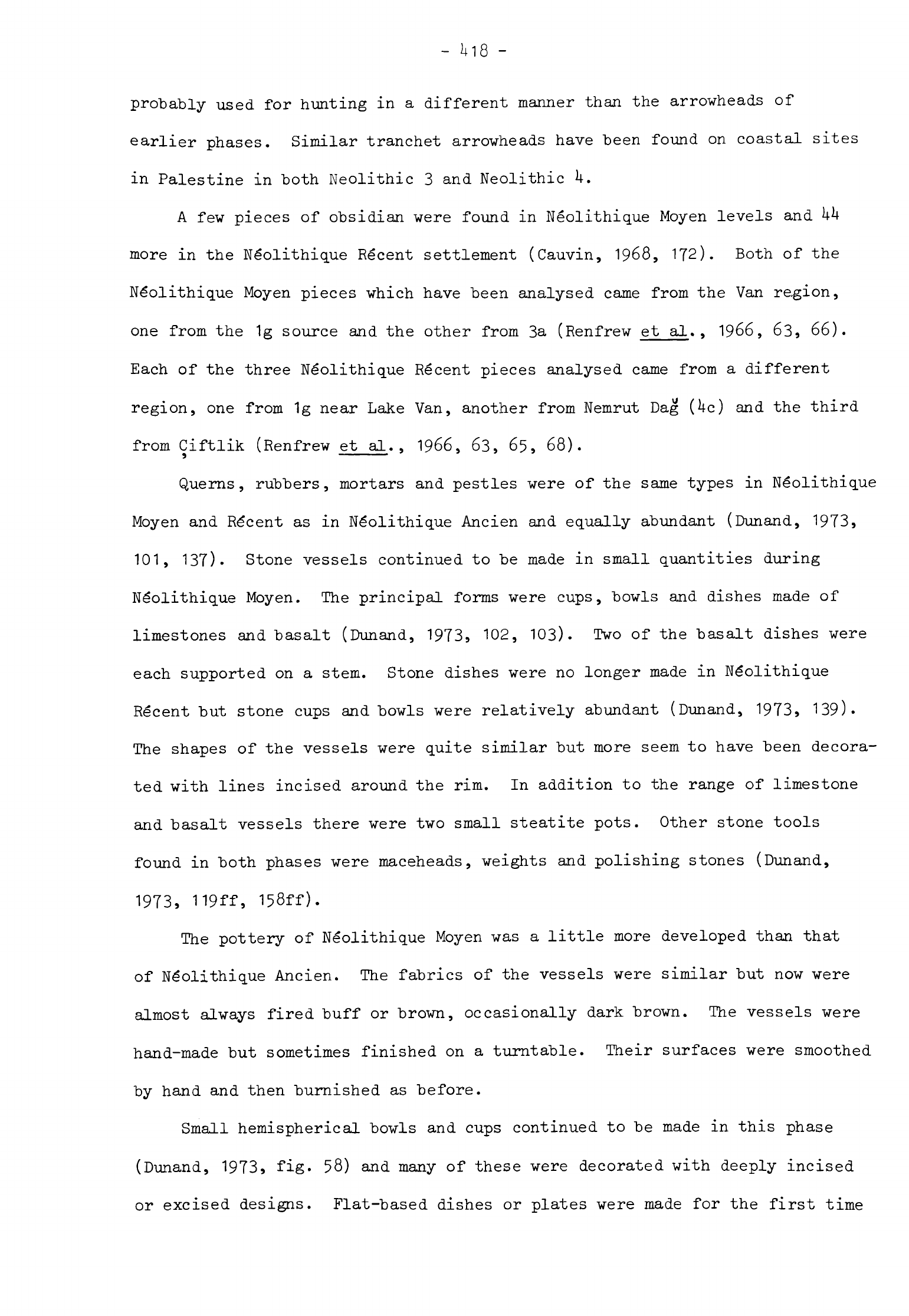

phases was

the

introduction

of

pottery.

This

new

artifact

is

the

main

distinguishing

feature

between

Phases

V

B

and

V

A

and

Phase

V

C.

The

earliest

pottery found

on

the

site

was

a

lightly

fired

crumbly

ware.

Sherds

of

this

pottery

were

found

in

some

quantity

at

the

bottom

of

the

V

B

layers

in

the

Palace garden

sounding

(Kuschke,

1962, 261)

but

only

a

handful

were

found

in

the

sounding

west

of

the

Temple

of

Baal

(de

Contenson,

1962,

50?).

The

most

common

class

of

pottery

was

a

series

of

thick-walled

vessels

made of

a

dark

fabric

with

grit

and

vegetable

filler

which

had

been

fired

quite

hard.

There

were

hemispherical

bowls,

globular

hole-mouth

jars,

jars

with

a

collar

neck

and

other

simple

shapes

(de

Contenson,

1962,

503,

507)

They

had

rounded

or

ring

bases

and

a

few

were

fitted

with

handles

or lugs

for

carrying.

One

or

two

fenestrated

bases

were

found

but

as

the

pieces

were

incomplete

we

do

not

know

how

they were

used.

The

surfaces

of

all

these

-

301

-

vessels

had

been

partly

or

completely

"burnished

and

a

few

were

decorated

with

incisions

or

even

red

paint.

One

unusual

group

of

vessels

made of

the

same

ware

was

a

series

of

"husking

trays"

found

in

Phase

V

A

(de

Contenson,

1962,

fig.

25)

which

resembled

those

found

in

Levels

II

to

VI

at

Tell

Hassuna

(Lloyd,

Safar,

19^5,

277ff).

Ras

Shamra

is

the only

site

in

the

Levant

at

which

these

unusual

vessels

have

been

discovered

so

it is

difficult

to

assess

their

significance

but

they

are

so

similar

to

the

Hassuna

examples

that

they

must indicate

a

cultural

connection

between

the two

regions.

Phase

V

A

immediately

precedes

Phase

IV

C,

the

phase

in

which Halaf

material

occurs,

so

the

"husking

trays"

may

be

the

first

indications

of

that

north

Mesopotamian

influence

which

became

so

marked

later

on.

The

third

class

of

vessels

was

a

group

of

thin-walled

globular

or

carinated

bowls

and

jars

with

short necks

made

from

a

dark

fabric

which

again

had

been

quite

hard

fired.

The

vessels of

this

fine

ware were

coloured

black,

brown

or

red

and

had

been

highly

burnished.

Some

of

them

were incised

with

a

dot

pattern

after

firing.

Another

characteristic

form

of

decoration

found

in

Phase

V

A

was

"pattern

burnishing"

in

which

a

series

of

lines

had

been

drawn

on

the

surface

of the

vessels

with

the

burnishing

tool

to

create

herring-

bone

and

diamond

patterns

(de

Contenson,

1962, figs. 26,

27).

The

name

"dark-faced

burnished

ware"

was

given

by

the

Braidwoods

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

U9ff)

to

a

broad

category

of

black

and

brown

burnished

vessels

at

Tells

Judaidah

and

Dhahab.

This

term

has

since

been

used by

archaeologists

to

describe

almost

all

types

of

simple

burnished

pottery

found

on

Neolithic

3

sites

in

the

Levant

and

in

the

process

has

lost

much

of

its

descriptive

value.

For

this

reason

I

propose

to

avoid

using

the

phrase

except

when

discussing

material

from

the

Amuq.

sites

for

which

it

was

invented.

Another

term

is

still

needed

to

describe

that

class

of

highly-burnished

black

and

brown

fine

ware

found

at

Ras

Shamra

in

Phases

V

B

and

V

A, in

Amuq

B

and

on

other

sites

in

Syria.

I

propose

to call

this

distinctive

pottery

"dark

polished

ware".

One

other

group

of

sherds

was

found

in

Ras

Shamra

V

B.

These

had

a

white

-

302

-

plaster

coating

(de

Contenson,

1962,

507),

perhaps

to

make then

more

water-

tight.

Similar

sherds

were

found

at

Byblos

in

Neolithic

3

"but

neither

there

nor

at

Ras

Shamra

did

this

class

of

pottery

continue

in

use

very

long.

There

were

several other

classes

of

artifacts

in

these

levels

at

Ras

Shamra.

Fragments

of

stone

bowls

and

dishes

were

quite

common

(de

Contenson,

1962,

505);

these

were usually

made

of

limestone

"but

there

were

basalt

ones

too.

A

number

of small

polished

stone

axes

were

found

and

also

stone

grinding

tools

such

as

rubbers

and saddle

querns.

The

bone

industry

included

borers

and

hafts

for

other

tools.

Baked

clay

was

used

for

objects

other

than pottery,

one

of

which

was

a

spoon

and

another

a

stamp

seal

with

a

simple

linear

design

(de

Contenson,

1962,

5.05

9

fig-

32).

The

stamp

seal

seems

definitely

to

have

been

used

to

print

a

design

on

other

objects.

Personal

ornaments

made of

polished

stone

or

shell

were

another

abundant

group

of

artifacts

at

Ras

Shamra.

One

ll

*C

determination

has

been

obtained

for

each

of

these

two phases

at

Ras

Shamra,

5736

±

112

B.C.

P-U58

for V

B

and

523U

±

Qk

B.C.

P-U57

for

V

A

(de

Contenson,

196U,

U7).

Since

the

transition

from

Phase

V

C

to V

B

took

place

at

or

a

little

after

6000

B.C.

Phases

V

B

and

V

A

lasted

for

most

of

the

6th

millennium

on

the

evidence

of

these

dates.

These

are

the phases

that

fall

in

Neolithic

3

for

with

the

advent of

Phase

IV

C

the

occupation

at

Ras

Shamra

takes

a

different

course

from

that

on

other

sites

further

south

in

the

Levant.

Tell

Sukas

Tell

Sukas

lies

on

the

coast

of

Syria

6

km

south

of

Jeble.

It

is

situated

on a

promontory

between

two

small

bays

which

served

as

harbours

in

ancient

times;

two

streams

flow

into

these

bays

on

either

side of

the

site

(Riis,

Thrane,

197**>

8).

The

earliest

settlement

was

a

Neolithic

village

founded

on

a

low

natural

rise

about

U.5

m

above

sea

level.

This

was

covered

by

debris

from later

periods

of

occupation.

The

remains

of

the

Neolithic

settlement

were

found

at

the

bottom

of

a

sounding

made

beneath

the

later

city.

The deposit

was

3

m

deep.

The

earliest

occupation

(period

N11)

consisted

of

traces

of

plaster

floors

and

a

pit

60

cm

-

303

-

in

diameter

dug

into

the

natural

subsoil

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

10ff).

Above

this

were

several

layers

in

which

remains

of

"buildings

were

found

(periods

N10-N6).

These

structures

were

rectilinear

with

at

least

two

rooms

in

some

instances

and

were

orientated

north-south.

The

walls

had

stone

footings

with

clay

or

mud-brick

walls.

Associated

with

these

buildings

were

plastered

and

trodden

floors,

pits,

hearths

and

much

occupation

debris.

The

upper

levels

(periods N5-N1)

consisted

of

more

plaster

floors

and

other

surfaces

with

pits

and

hearths

but

the

only

structure

was

a

stone

wall

found

in

layer

63

(Riis,

Thrane,

197**,

70).

The

remains

found

in

these

levels

indicate

that

the

area

excavated

was

then

an

open

space

between

buildings.

An

area

of

dark

loam

was

found

over

part

of

N1

which

was

thought

to

have

been

formed

after

the

Neolithic

settlement

was

abandoned

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

80).

The

layer

above

this

has

been

dated

by

a

lk

C

determination

of

3960

±

100

B.C.

K-936

(Radiocarbon

15,

1973,

108)

so

occupation

of

the

Neolithic

settlement

must

have

ceased

well

before

to

allow

the

soil

to develop.

Relatively

few

flint

tools

were

found

at

Tell

Sukas,

doubtless

because

the

sounding

was

so

small.

Among

them

were

a

number

of

Amuq

1

and

2

arrow-

heads,

leaf-shaped

and

tanged

arrowheads,

a

few

sickle

blades,

a

burin

and

some

flake

scrapers

as

well

as

retouched

blades

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

*+0,

18,

16).

Obsidian

was

used

throughout

the

life of

the

Neolithic

settlement.

Other

stone artifacts

were

also rare

but

they

included

polished

axes

and

adzes,

basalt

querns

and

rubbers,

and

bowls

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

16,

55,

36,

80,

63).

Potsherds

were

abundant

in

nearly

all

the

layers.

Many

of

the

vessels

were

simple

in

shape,

consisting

for

the

most

part

of

hemispherical

bowls

and

collared

jars

with

ledge

handles

for

lifting

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

23).

These

vessels

were

usually

black,

grey

or

brown

in

colour

with

a

burnished

surface

although

unburnished

pots

were

also

made.

Some

vessels

had

incised,

impressed

or

combed

decoration,

particularly

in

the

later

phases,

and

a

few

were

painted

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

63,

68,

19).

Others

had

a

plaster

coating

and

one

was

pattern

burnished

(Riis,

Thrane,

197*+,

52,

18).

White ware

was

also

present

-

SOU

-

throughout

and

again

the

vessels

were

simple

in

shape.

The

two

principal

types

were

open

bowls

with

splayed

sides

and

hemispherical

bowls

some

of

which

had

ring

bases

(Riis,

Thrane,

197U,

26,

77);

a

few

of

these

vessels

were

painted.

The

buildings

and

artifacts

from

Tell

Sukas

have

much

in

common

with

Ras

Shamra,

particularly

in

Phase

V

B.

The

site thus

appears

to

have

been

first

occupied

early

in

the

6th

millennium

and

then

continuously

inhabited

until

quite late

in

Neolithic

3.

Tell

Sukas

may

be

ascribed

to

the

North

Syrian

group

although

it

has

certain

traits

such

as

impressed

and

combed

decoration

on

pottery

in

common

with

Tabbat

el

Ham-mam

and

other

sites

further

s

outh.

Qal'at

er-Rus

6

km

north

of

Jeble

may

also

have

first

been

occupied

in

Neolithic

3

since

plain

burnished

and

pattern

burnished

vessels

were

found

in the

lower

levels

(Ehrich,

1939,

10,

18).

Kama

The

River

Orontes

is

deeply

incised

into

the

Syrian

plateau

at

Hama.

The

ancient

mound

lies

on

a

terrace

in

the

valley beside

the

river

in

the

heart

of

the

modern

town.

The

site

was

excavated

from

1932

to

1938

but

only

the

upper

levels

were

cleared

to any extent.

A

Roman cistern

was

cleaned

out

and

below

this

a

sounding

was

dug

to

the

sterile

subsoil

(Fugmann,

1958,

12).

The

sounding

took

the

form

of

a

circular

shaft

1.5

m

in

diameter

which

enabled

the

excavators

to

ascertain

the

stratigraphic

sequence

but

was

too

narrow

for

much

to

be

learned

about

the

nature

of

the

earlier

settlements

(Fugmann,

1958,

pi.

IX).

This

deep

sounding,

G

11

X,

was sunk

in

the

northern

sector

of the

mound

near

the

river

(Fugmann,

1958,

fig.

9).

It

was

found

that

the

earliest

settlement

of

Period

M

was

established

on

the

natural

subsoil

and

that

the

deposit

was

6

m

deep.

Such

a

considerable

accumulation

of

debris

suggests

that

the

settlement

was

substantial

but

we

do

not

know,

of

course,

how

extensive

it

was.

Some

of

the

layers

were

ashy

and

others

pebbly.

These

-

305

-

were presumably

the

remains

of

occupation

debris

and

floors.

There

was

also

a

little

painted

plaster

from

buildings,

the

only

indication

of

substantial

structures.

The

finds

were

meagre

simply

because

the

sounding

was

so

small.

Pottery

of

two

sorts

was

found

throughout

Period

M.

One was

a

thick

coarse

ware

and

the

other

a

finer

ware

which

had

been

coloured

red

or

black

and

burnished

(ingholt,

19^-0,

11);

some

of

these

sherds

were

also

incised.

The

only

other

finds

reported

were

flint

and

obsidian

blades.

The

layers

of

Period

M

were

stratified

beneath

those

of

Period

L

which

contained

Halaf

pottery.

Its

position

in

the

stratigraphic

sequence

and

the

nature

of

the

pottery

indicate

that

the

settlement

of

Period

M

was

occupied

in

Neolithic

3

and

can

be equated

with

Ras

Shamra

V

B

and

V

A.

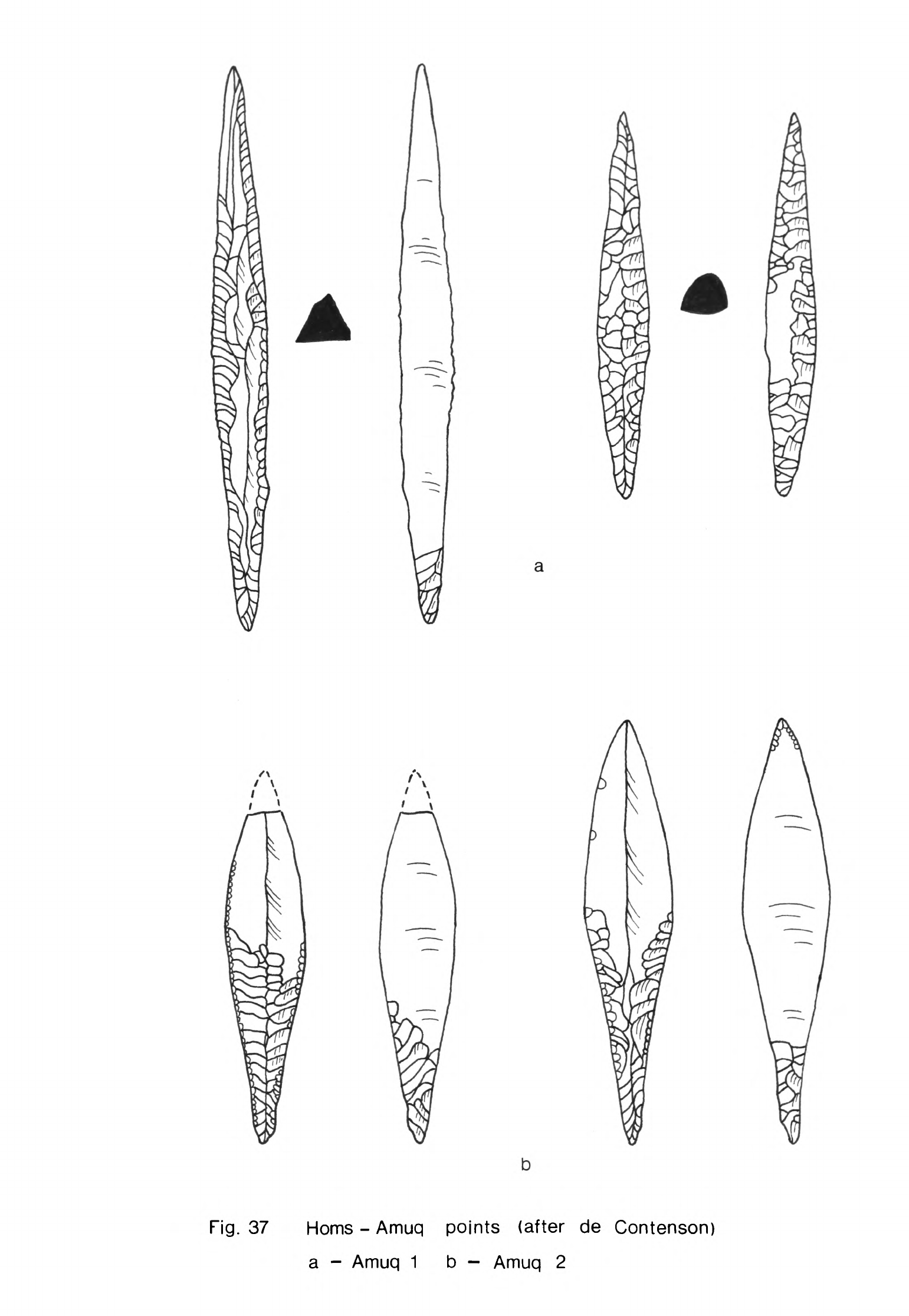

Horns

A

series

of

flints

was

collected

from

the

surface

of

a

prehistoric

site

near

Horns

and

is

now

in

a

private collection

(de

Contenson,

1969c,

63).

They

formed

a

homogeneous

group

and

can

be

quite

closely

dated

on

their

typology.

They

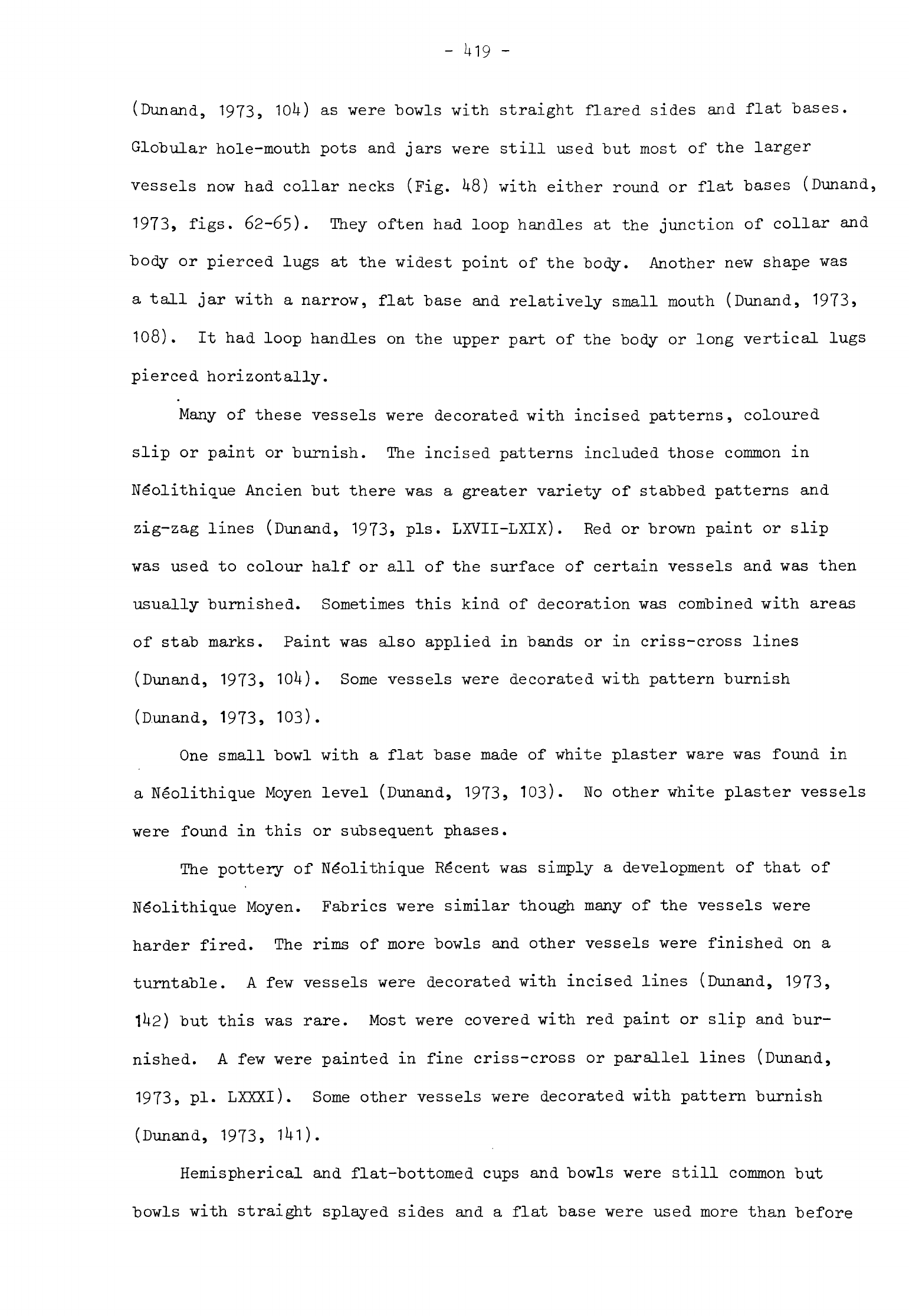

consisted

of

eight arrowheads and

eight

blank

blades.

The

arrowheads

were

all

Amuq

points,

that

is

long

pointed

blades

of

triangular

cross-section

with

a

stem

retouched

by

pressure-flaking

to

form

a

blunt

point.

Cauvin

has

defined

two

types

of

Amuq

point,

type

1

shaped

like

a

willow

leaf

with

retouch

over

much

of

the

ventral

and

sometimes

also

the

dorsal

surfaces

and

type

2

made

on

a

broader

blade

with

one

end

narrowed

by

retouch

to

form

a

tang

(Cauvin,

1968,

U9,

53).

Both

types

were

present

in

the

Horns

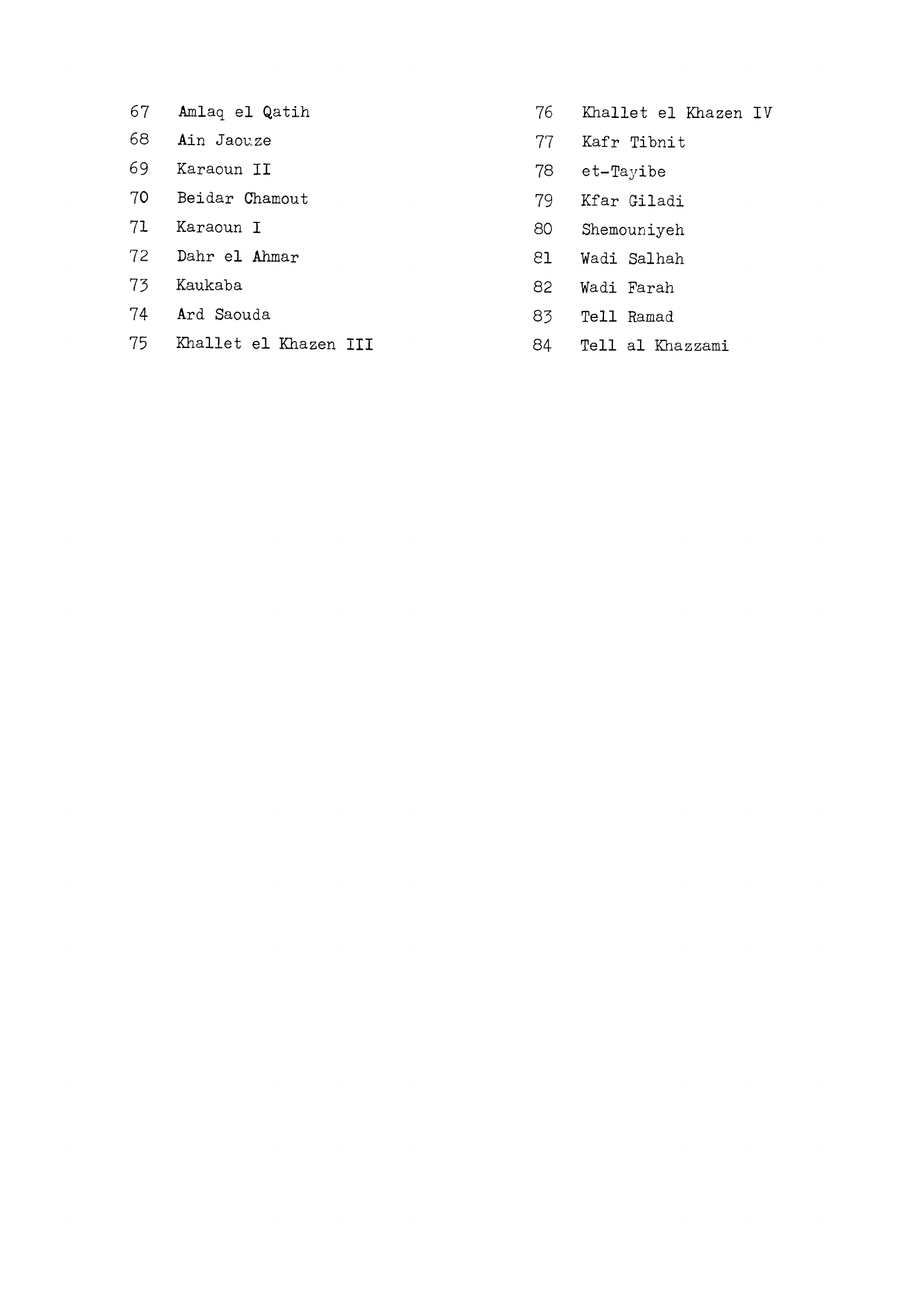

collection

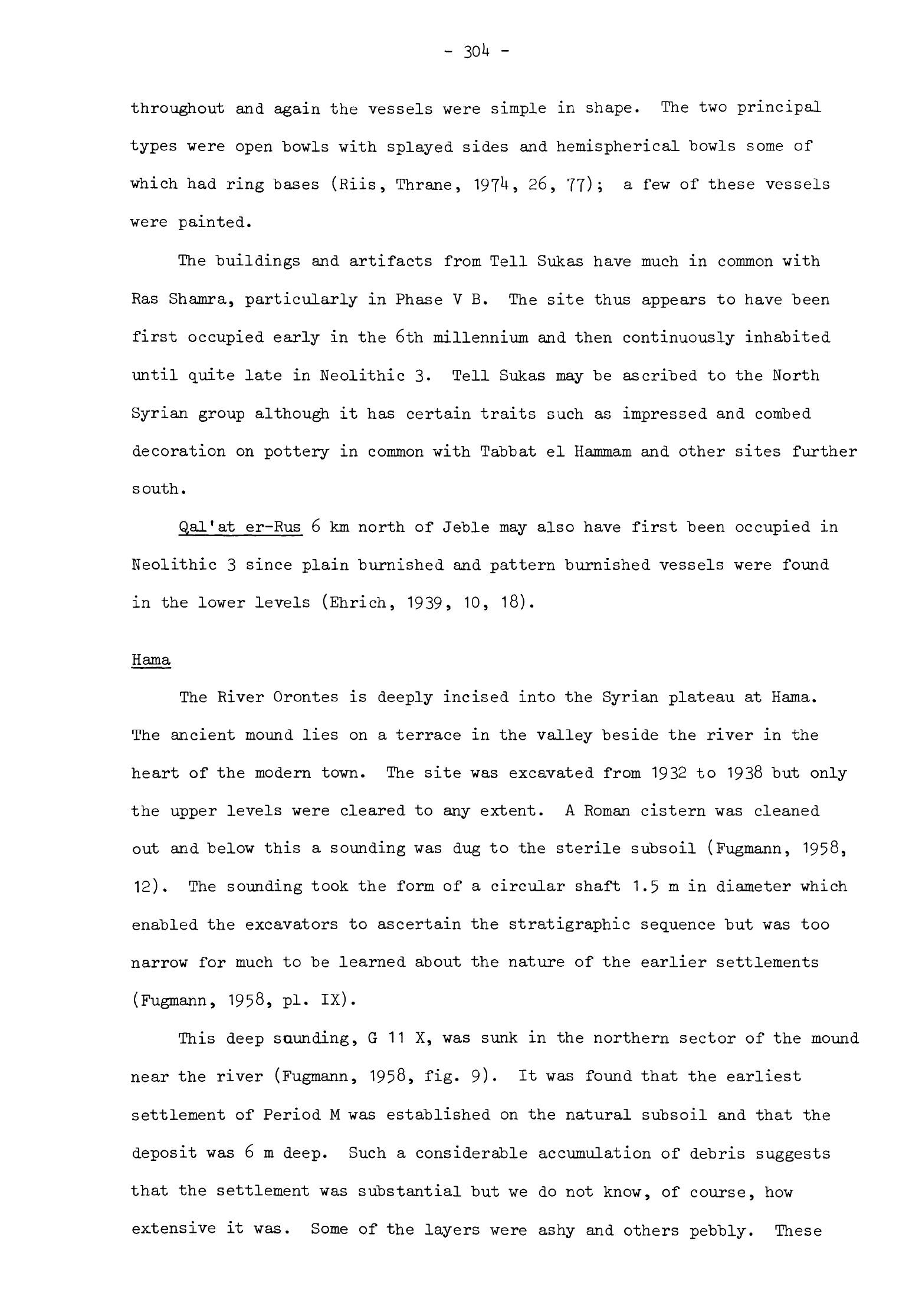

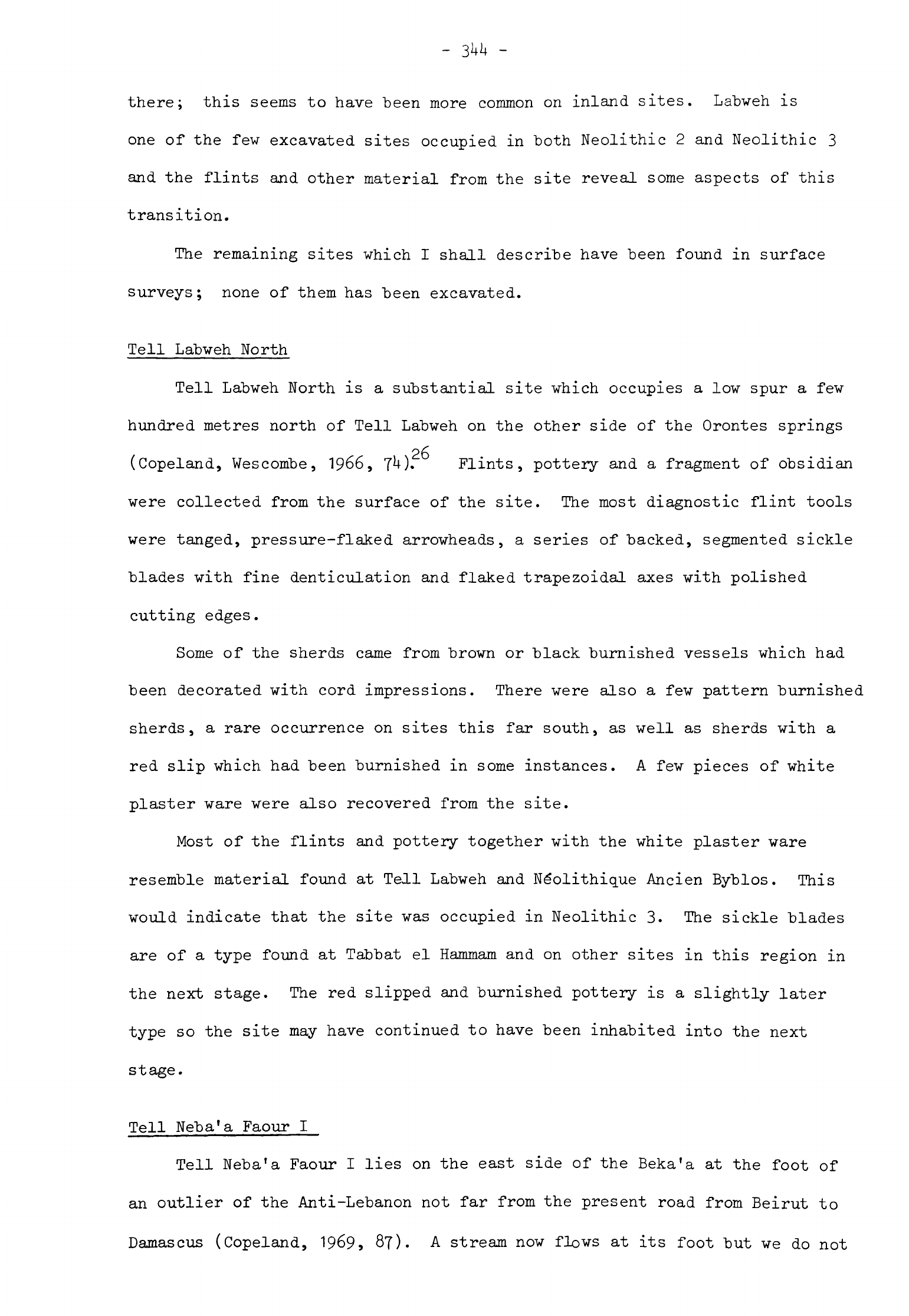

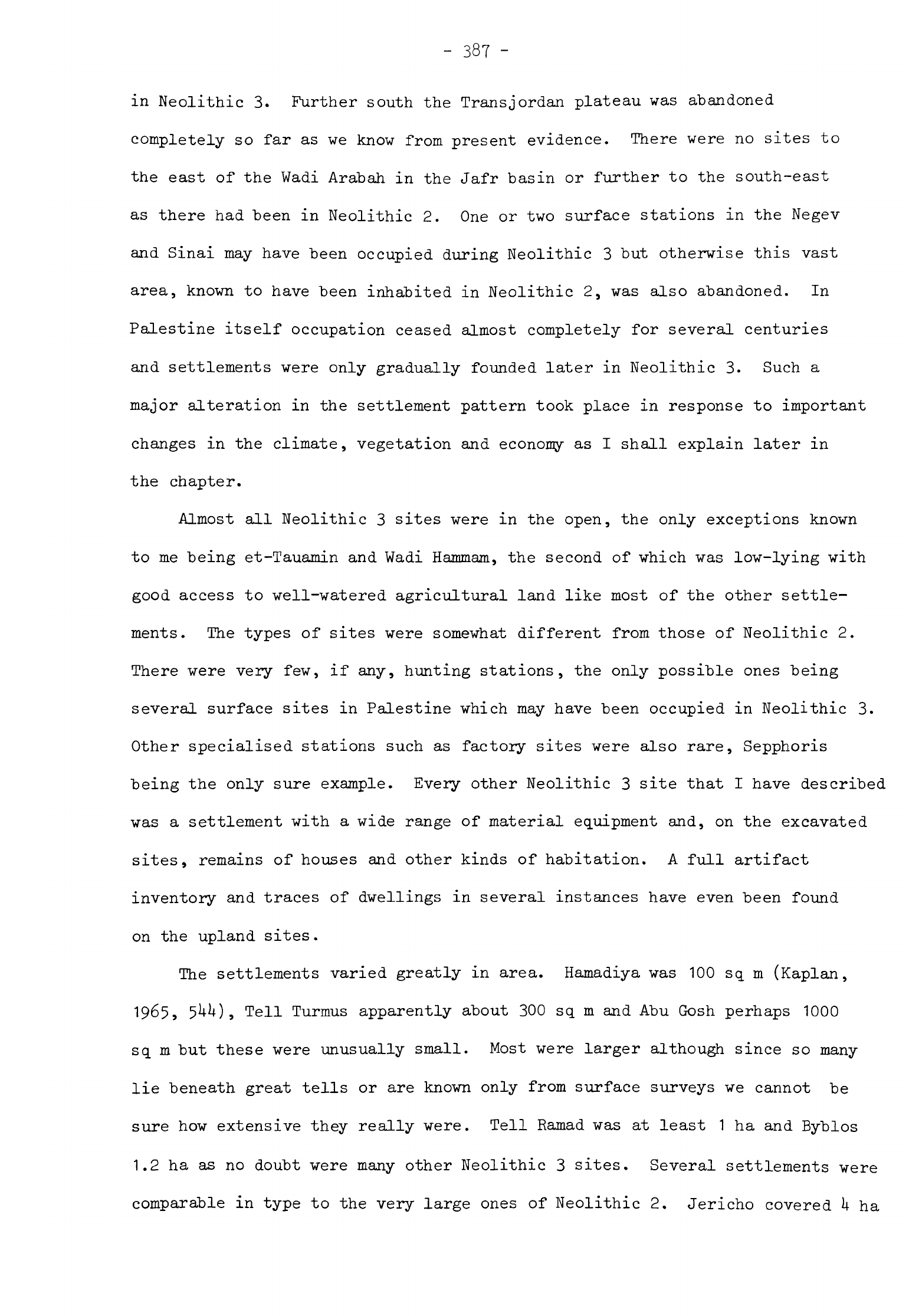

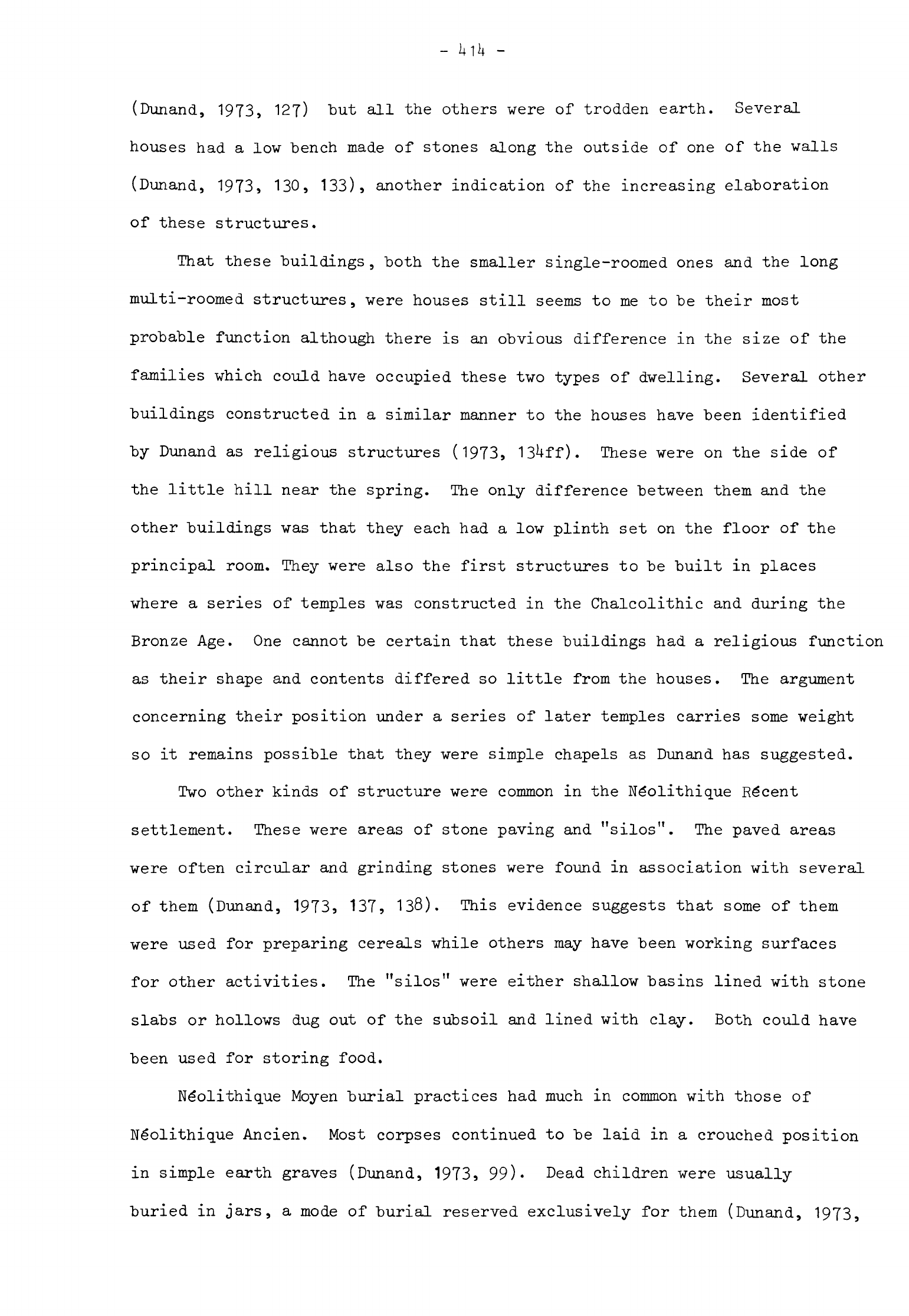

(Fig.

37).

Amuq

points

have

been

found

in

late

Neolithic

2

contexts

such

as

the

later

aceramic

Neolithic

levels

at

Abu

Hureyra

and

in

Ras

Shamra

V

C

(de

Contenson,

1969c,

65).

They

are

more common

in

Neolithic

3

recurring

in

both

Ras

Shamra

V

B

and

Ne"olithique

Ancien

and

Moyen

at

Byblos

as

well

as

in

Amuq

A

and

B

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960, figs.

30,

60,

37^;

pi.

65).

Thus

the

Horns

site

may

have

been

occupied

in

Neolithic

2

but

it

is

more

likely

it

was

Fig.

37

Horns

-

Amuq

points

(after

de

Contenson)

a

-

Amuq

1

b

-

Amuq

2

-

306

-

inhabited

in

Neolithic

3

sometime

during

the

6th

millennium

B.C.

Qal'at

el

Mudiq

Qal'at

el

Mudiq

lies

north-west

of

Kama

overlooking

the

valley

of

the

Orontes

from

the

east.

Numerous

flint

tools

and

scraps of

obsidian

have

been

found

on

the

lower

slopes

of

the

castle

mound

which

probably

came

from

the

earliest

levels

of

occupation

at

the

site.

The

few

diagnostic

tools

were

an

Amuq

arrowhead

and

several

segmented

sickle

blades

(Dewez,

1970,

pis.

11:5,

111:1-10.

Most

of

the

flakes

and

blades

found

had been

struck

off

prismatic

cores.

This

scanty

information

would

suggest

that

Qal'at

el

Mudiq

was

occupied

during

the

Neolithic,

probably

in

stage

3.

Janudiyeh

The

site

of

Janudiyeh

is

situated

on

the

heights

above

the

west

bank

of

the

Orontes

north

of

Jisr

esh-Shaghur.

Both

flint

tools

and

potsherds

have

been

collected

from

the

surface and

it

is

possible

to

ascertain

from

these when

the

site

was

occupied.

Many

of

the

flints

were

Amuq

arrowheads

of

both

types

1

and

2

while

there

were

also

retouched blades,

a

sickle

blade

and

flake

scrapers,

among

them

several

discoids

(de

Contenson,

1969c,

68ff).

The sherds

all

belonged

to

vessels

of simple

shapes

such

as

hemispherical

bowls

and

jars

with

hole-mouths

or

collared

necks

(de

Contenson,

1969c,

TO).

Almost

all

were

dark

in

colour

with

a

burnished

surface

while

a

few

had

incised

decoration.

The

flints

and

the

pottery

are

similar

to

the

material

found

at

Ras

Shamra

in

Phase

V

B

so

the

site

was

occupied

quite

early

in

Neolithic

3.

The

site

itself

is

unusual

as

it

is

at

an

elevation

of

about

500

m

in

what

was

then

forested,

hilly

country.

There

is

cultivable

land

nearby

so

Janudiyeh

could

have

been

either

an

agricultural

or

a

pastoral

settlement.

The

extreme

north-west

corner

of

the

Levant

is

today

the

Turkish province

of

the

Hatay.

The

Amanus

Mountains

on

the

west

separate

most

of

the

region

-

307

-

from

the

Mediterranean.

Behind

them

to

the

east

lies

the

Amuq

plain

and

here

the

Orontes

after flowing

north

through

Syria

turns

south-west

to

meet

the

sea.

Several

roads

pass

from

the

plain

through

low

hills to

the east

up

to the

Syrian

plateau

so

that

geographically

the

region

is

more

an

extension

of

Syria

than

a

part

of

Turkey

although

there

is

also

an

easy

route

to

the

north

up the

valley

of

the

Karasu.

The

fertile

plain

is

dotted

with

ancient

settlements

and

several

of

these

have

"been

shown

in

excavations

to

have

been

occupied

as

early

as

Neolithic

3.

The

remains

of

the

Neolithic

settlements

are

always

found

to

be

well

below

the

present

level of

the

plain

because

an

enormous

amount

of

alluvium

has

accumulated

since

the

lower

course

of

the

Orontes

was

blocked

in

the

earthquakes

that

destroyed

ancient

Antioch.

It

is

known

that

the

region

has

been

inhabited

since

the

lower

Palaeolithic

from

discoveries

made

in

the

hills

around

the

Amuq

plain

(Hours

et

al., 19T3

9

2U2)

but

sites

dating from

Neolithic

1

and

2

have

not

yet

been

found

there.

Any

settlement

sites

of

this date

founded

on

the

plain

itself

would

have

subse-

quently

been

buried.

Much

of

our

information

about

the

sequence

of

Neolithic

occupation

on

the

Amuq

plain

comes

from

the

excavations

of

the

Oriental

Institute

of

CTiicago

University

at

Tell

Judaidah

and

Tell

Dhahab

both

of

which

lie

in

the

south-

eastern

corner

of

the the

Amuq

plain

near

Rehanli.

The

Neolithic

deposits

at

Tell

Judaidah,

designated

level

XIV,

were

divided

on

the

typology

of the

pottery

into

two

phases,

A

and

B,

both

of

which

fall

in

Neolithic

3.

The

only

Neolithic

occupation

at

Tell

Dhahab

was

a

short-lived

settlement

of

phase

A

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

U6).

Tell

Judaidah

The

lowest

layers

reached

at

Judaideh

were

below

the

water

table

which

seriously

impeded

the

excavation and

limited

the

information

that

could

be

recovered

from

the

deep

sounding

made

there.

No

buildings were

found

in

phase

A

though

they

may

have

existed

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

-

308

-

Remains

of

rectilinear

buildings

with

stone

foundations

and

perhaps

mud-brick

or

mud

walls

were

found

in

the

phase

B

layers

above

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

68).

23

The

chipped

stone

industry

was

of

the

same

character

throughout

phases

A

and

B.

Most

of the

tools

kept

for

study

were

made

on

blades

struck

from

single-ended

pyramidal

or

conical

cores,

the

by-products

of

which

included

crested

blades

and

core

tablets.

The

most

abundant

tools

seem

to

have

been

arrowheads

and

sickle

blades

(Payne,

1960,

525,

526).

Many

of the

arrowheads

were

of

the

types

called

Amuq

1

and

2

by

Cauvin.

These

were

mostly

quite

long,

long

enough

to be called

javelin

heads

in

the

published

account,

although

on

ethnographic

analogy

all

could

have

been

used

to

arm

arrows

.

They

were

extensively

pressure-flaked

on

the

upper

surface

and

had

some

retouch

on

the

back

at

the

tip

and

tang.

Most of the

type

2

arrowheads

had

swollen

tangs.

Some

of

the

arrowheads

though

still

tanged

were

much

shorter

than

these

and

a

few

were

finished

with

abrupt

retouch.

All

the

sickle

blades

were

segmented

and

usually

about

3.5

cm

in

length.

Most

of these

blade

sections

had

been

snapped

off

at

the

required

length

although

a

few

were

made

by

the

notch

technique.

The

cutting

edge

of

many

of

the sickle

blades

had

been

slightly

retouched

but

they

were

not

backed.

Many

still

retained

traces

of

the

mastic

which

secured

them

in

the

sickle.

Among

the

other

tools

were

borers

on

blade

segments

and

single-blow,

angle

and

dihedral

burins. There

were

also

end-scrapers

on

blades

and

flake

scrapers

some

of

which

were

discoid

(Payne,

1960,

52?)

Obsidian

was

quite

plentiful

as

a

raw

material

and

was

worked

on

the

spot,

the

evidence

for

this

being

pyramidal

cores,

crested blades

and

core

tablets

(Payne,

1960,

528,

529).

Not

only

were

there obsidian

blades and

flakes

but

also

small

borers

and

arrowhead

tangs.

One

piece

has

been

analysed

from

Judaidah

which

was

found

to

have

come

from

the

Ciftlik

source

(Renfrew

et

al.,

1966,

65).

The

chipped

stone

industry

is

in

general

quite

similar

to

what

we

know

of

the

material from

Ras

Shamra

V

B

and

V

A

although

there

are

differences

in

the

-

309

-

types

of

sickle

blades

preferred

at

each site

and

the

quantities

of

obsidian present,

a

function

of

ease

of

communication

with

and

distance

from

the

sources.

The

other

stone tools

at

Judaidah were

both

abundant

and

varied.

Trapezoidal

stone

axes

and

adzes

were

particularly

common

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

58,

87).

These

were

quite

thin

and

had

straight

sides

with

a

bevelled

cutting

edge.

All

were

ground

and

partly

polished.

They

were

made

in

both

large

and

small

sizes

so

would

have

been

suitable

both

for

preparing

rough

timber

and

shaping

wooden

artifacts.

Disc rubbers

were

abundant

while

hammers

and

slingstones

were

also

present

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

55,

61, 86,

90).

One

macehead

was

found

in

the

phase

B

levels,

a

grooved

stone

in

phase

A

and

several

stamp

seals

in

both

phases

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

61,

63,

90,

9^).

The

stamp

seals

were

incised

with

geometric

patterns

which

in

most

cases

consisted

of

criss-cross

lines.

Spindle

whorls

were

made from

both

stone

and

baked

clay

while

circular

stone

dishes

were

also

used.

These

were

usually ground

and

polished

and

at

least

one

had

a

spout

for

pouring

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

fig. 32,

8).

Decorative

stone

objects

were

also

made,

among

them

two

studs,

pendants

and beads.

The

latter

included

several

butterfly

beads

of

the

kind

found

in

such

abundance

at

Abu

Hureyra

in

both

Neolithic

3

and

Neolithic

2

contexts (Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

figs.

36:

5~7,

67:7).

The

usual

bone

awls,

needles

and

spatulae

were

also

used

at

the

site

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

65-67,

97~99).

Three

principal

types of

pottery

have

been

distinguished

from

Judaidah

although

there

were

small

quantities

of

several

others

in

phase

B.

The

shapes

of the

vessels

were

quite

simple,

consisting

for the

most

part of

globular

hole-mouth

jars,

some

collared

jars

and

bowls

with

flat

bases.

The

most common

type

was

dark-faced

burnished

ware,

a

group

of

thick-walled

medium-fired

vessels

made

of clay

tempered

with

grit,

sand

and

some

organic

matter

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

^9ff).

When

fired

the

core

was

usually

dark

grey

or

black.

The

surface

colour

of

these

pots

varied

from

buff

to

-

310

-

black

but

most

of

them

were

in

shades

of

brown.

All

had

been

roughly

bur-

nished.

Surface

decoration

was

limited

to

jabs

and

incised

shell

or

finger-

nail

impressions

on

a

few

pots.

Some

jars

had

ledge

handles

for

lifting.

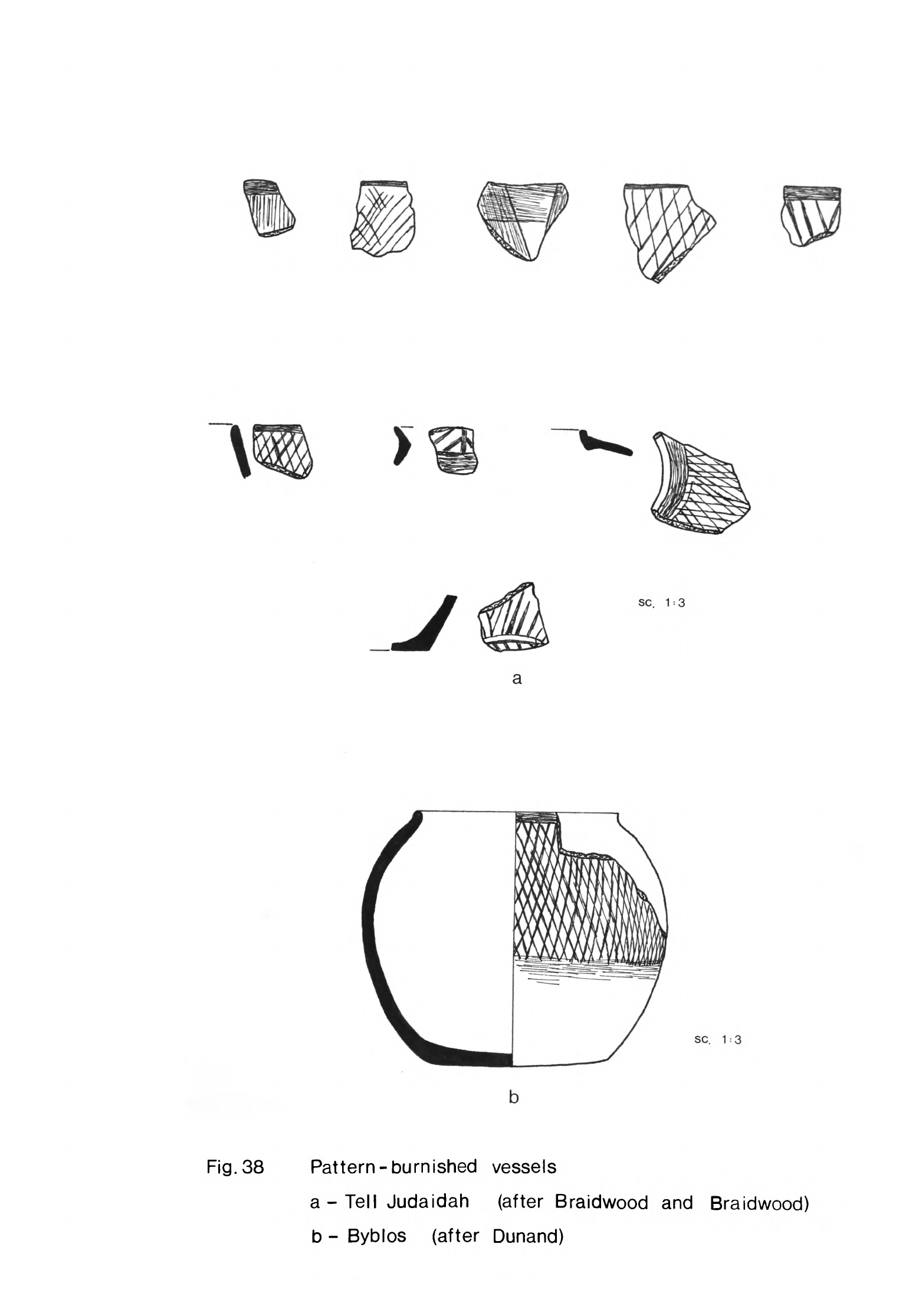

In

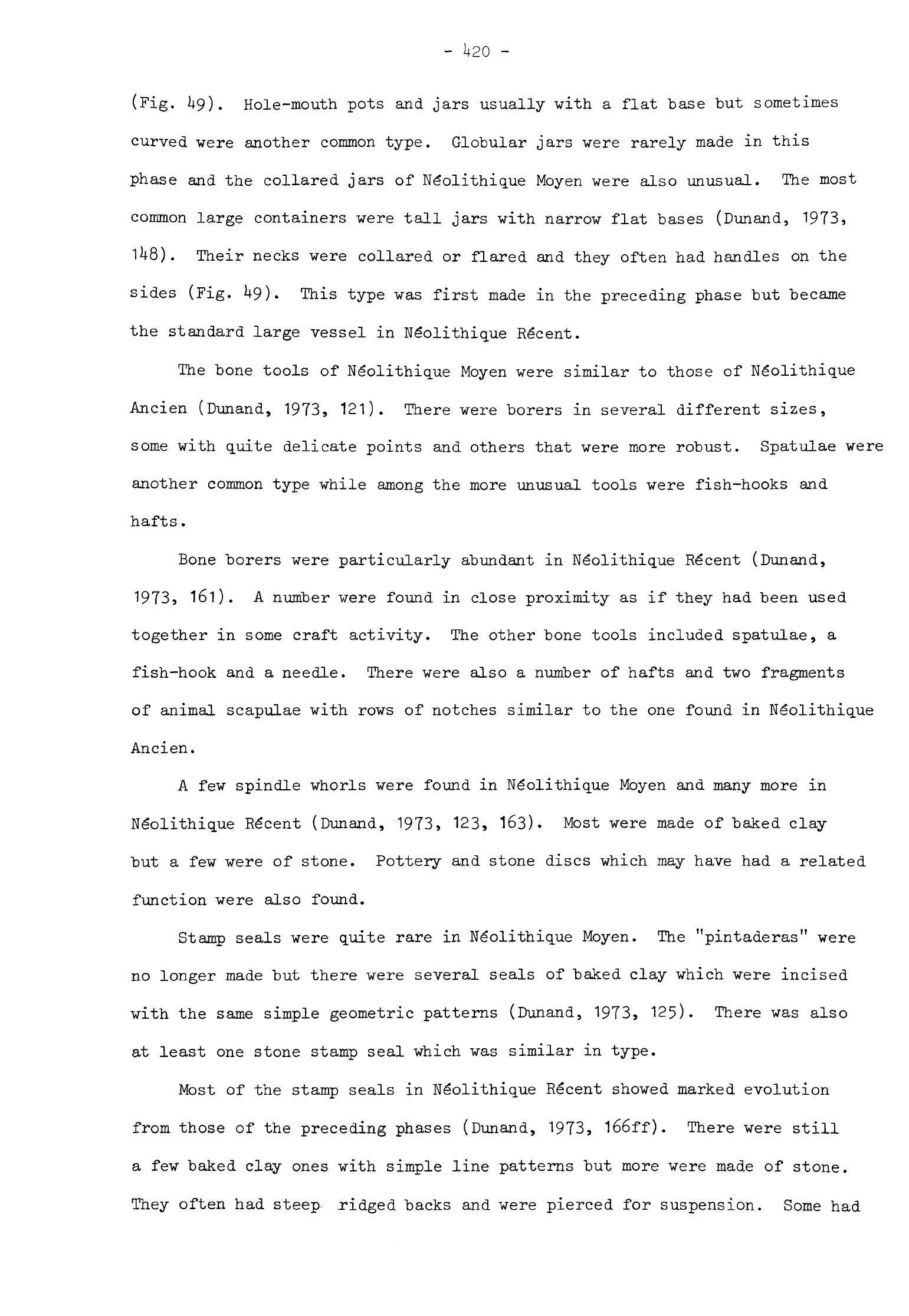

phase

B

certain

vessels

were

made

with

thinner

walls

and

given

more

even surface

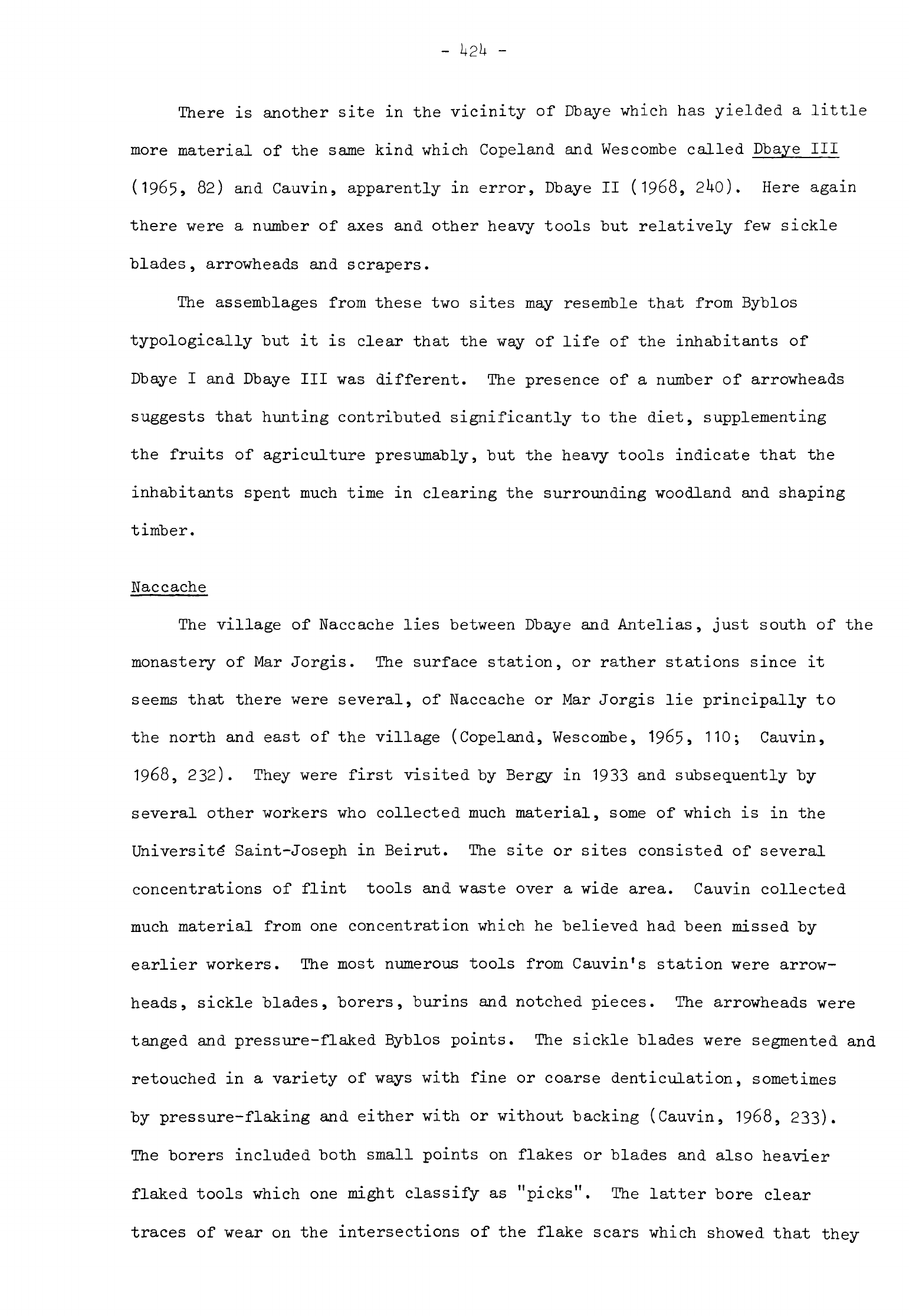

treatment

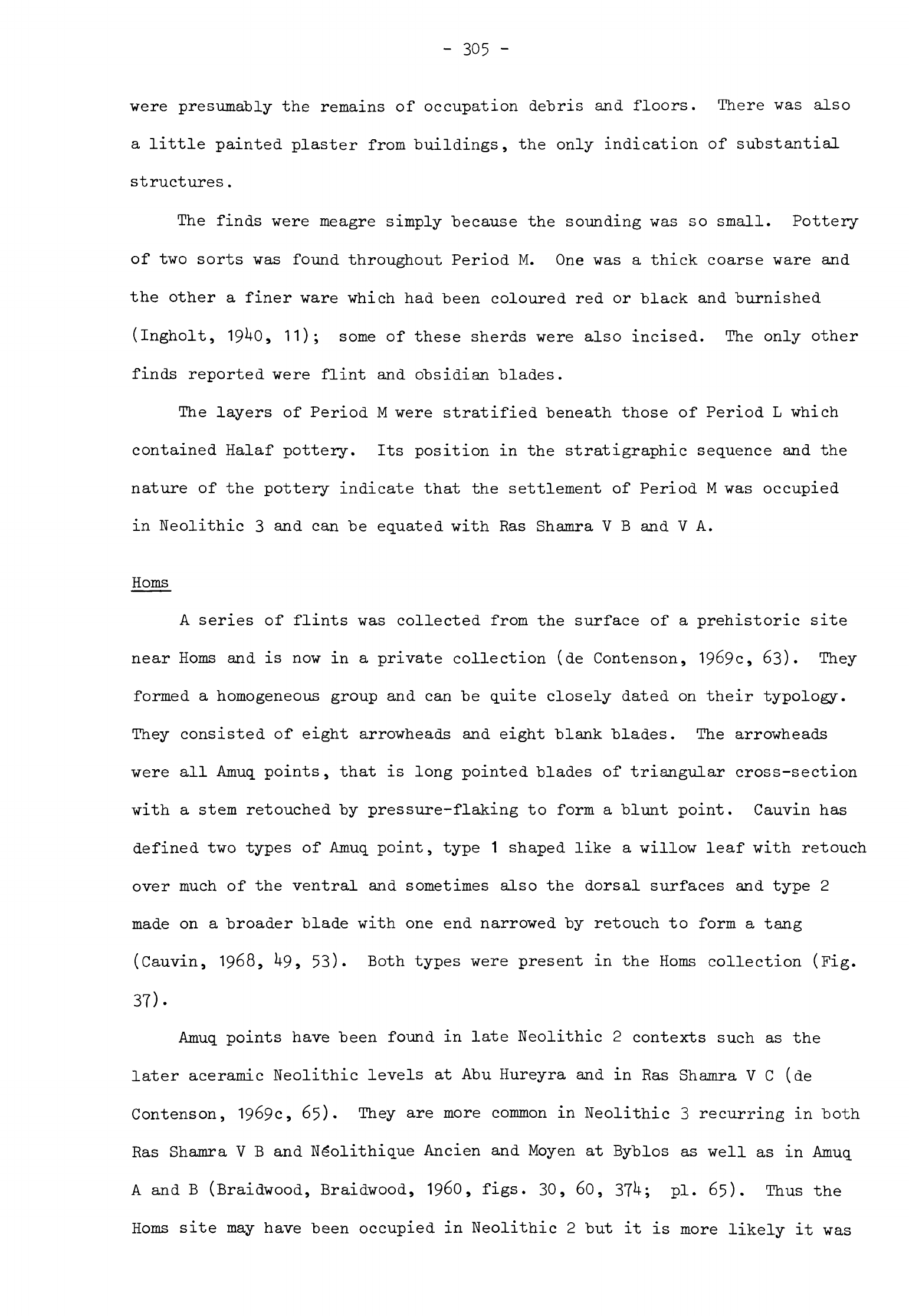

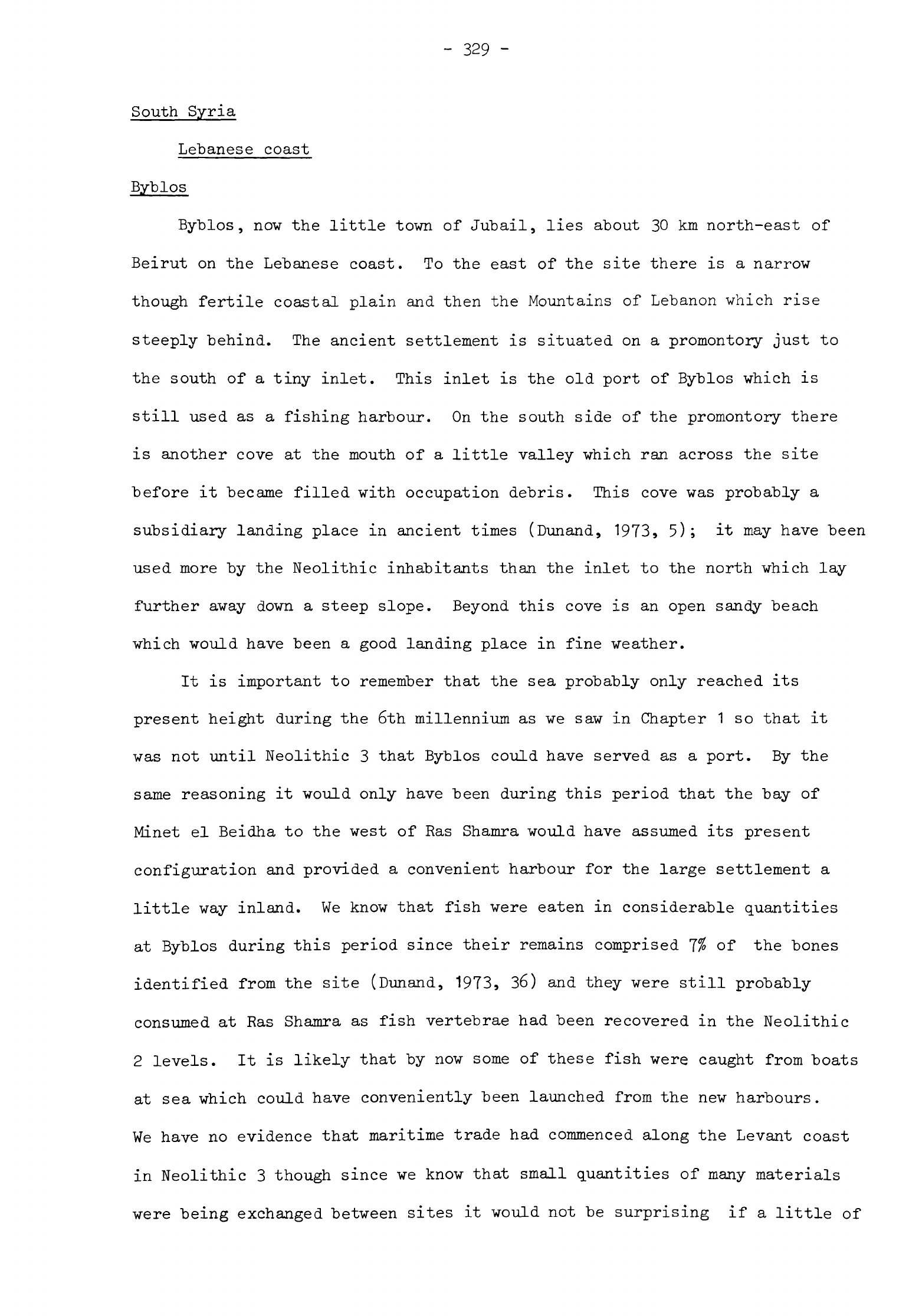

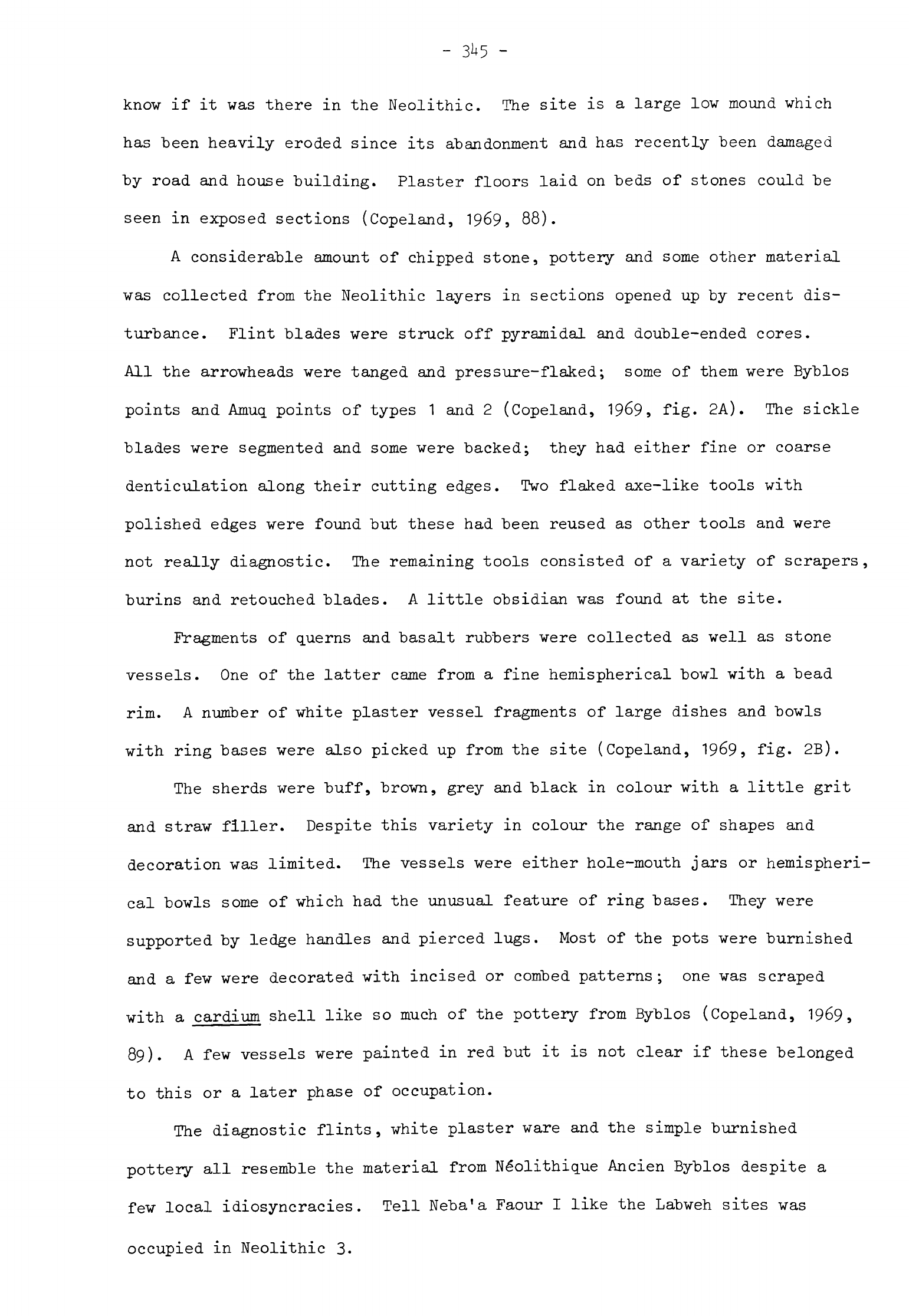

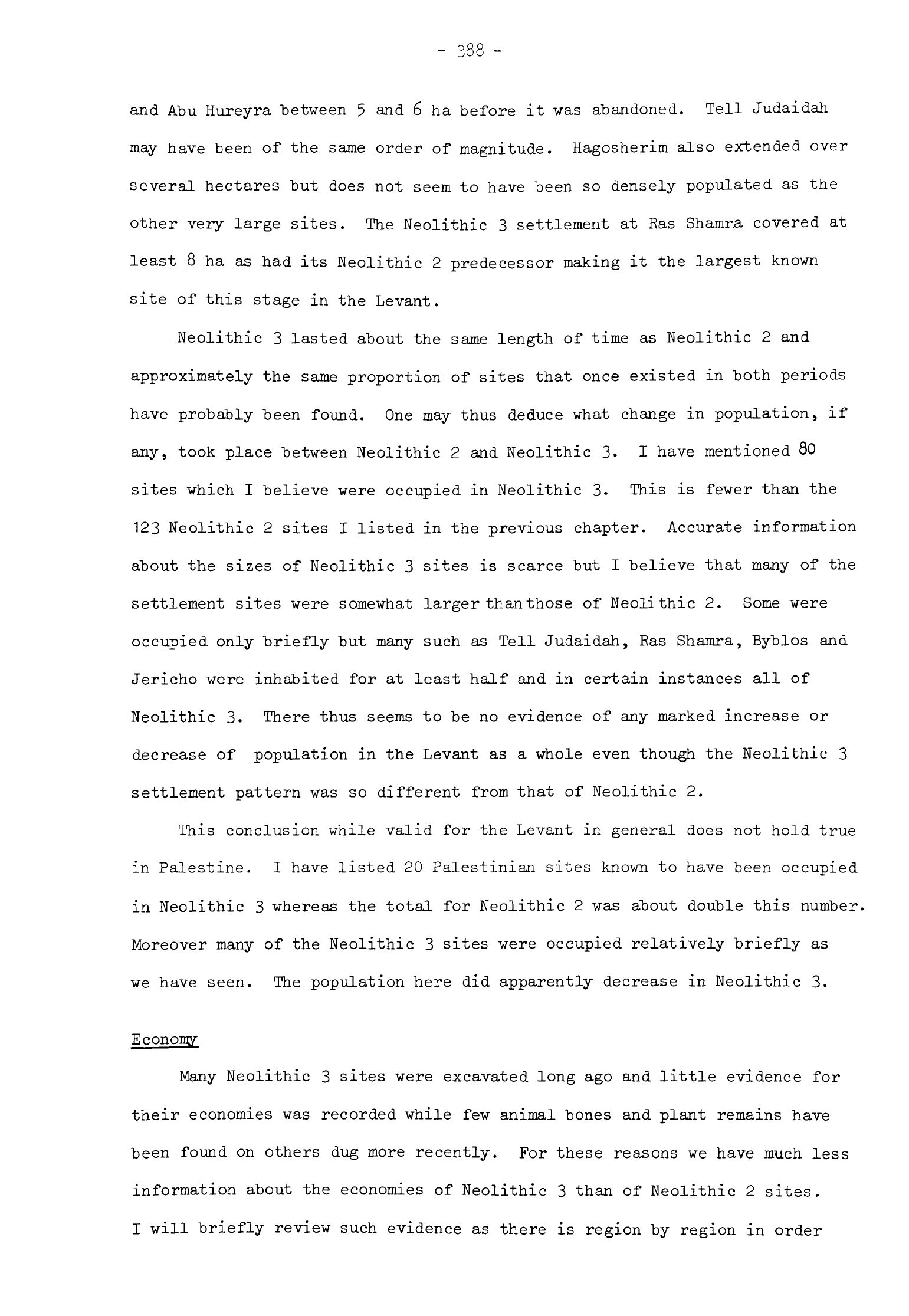

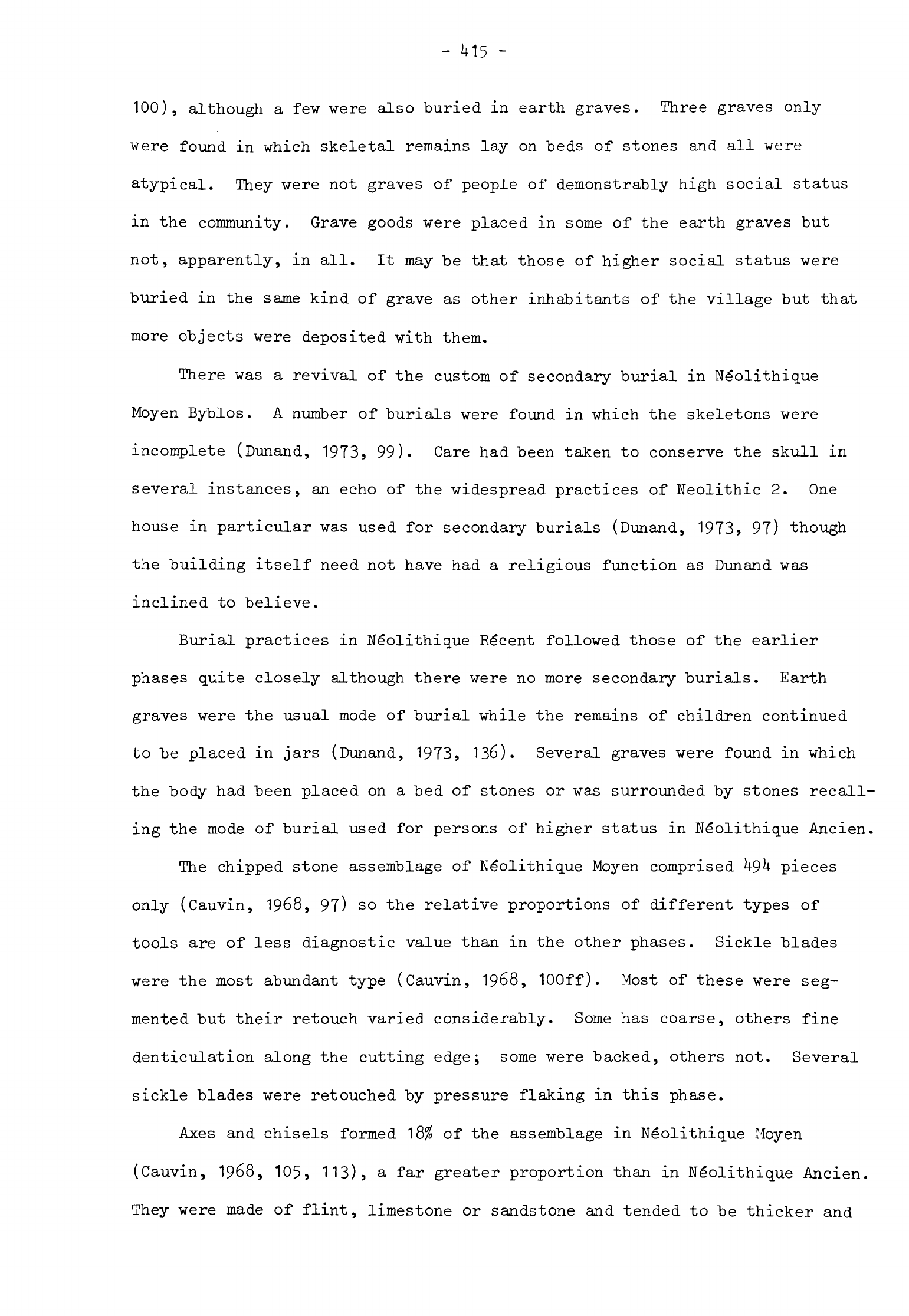

(Fig.

38).

Some

of

these

pots

were

decorated

with

pattern

burnish

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

77).

Carinated

bowls

were

made

for the

first

time

in

phase

B

which,

together

with

a

few

other

pots,

could

be

classed

as

dark

polished

ware.

The

second

type of

pottery

was coarse

simple

ware,

a

group

of

thick-walled

vessels

of

a

softer

fabric

with

much

straw

filler

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

U7ff)

The

surface colour

of

the

pots

ranged

from

light

buff

to

orange

and

brown.

The

third

type

was

washed

impressed

ware,

a

series

of

vessels

with

the

varied

surface

colours

of

the

other

varieties

but

which

had

been

partly

covered

in

thin

red

paint

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

52ff).

The

rims

were

painted

red

and

often

burnished

with

a

band

of

impressed

decoration

below

usually

done

with

the

edge

of

a

shell.

The

pottery

was

a

little

more

elaborate

in

phase

B

with

more

varied

surface

treatment

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

69).

A

number

of

vessels

were

coated

with

red

slip

and

burnished,

a

type

of

finish

quite

rare

in

phase

A.

A

brittle

painted

ware

could

be

distinguished,

the

vessels

of

which

were

painted

with

lines

of

reddish

paint

on

a

burnished

surface

(Braidwood,

Braidwood,

1960,

80ff).

Other

pots

were

decorated

more

extensively

with

incised

lines

and

shell-impressed

patterns.

Amuq

A

and

B

pottery

was

found

in

great

quantity

at

Judaidah

which

enables

us

to

see

just

how

varied

in

fabric

and

decoration

the

finished

product

was.

The

pots

were

probably

made

by

many

individuals

using

methods

that

would

have

been

irregular

and

subject

to

uncertainty.

The

vessels

were

probably

fired

in

bonfires

which

would

account

for

the

uneven

colours

and

textures

of

the

fabrics.

Because

the

pottery

was

made

in

this

way

the

result

was

bound

to

vary

considerably

from

site

to

site.

One cannot

use

pottery

at

\

J

SC.

1=3

SC.

1:3

Fig.

38

Pattern-burnished

vessels

a-Tell

Judaidah

(after

Braidwood