|

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) Ancient Hama -- Hamath -- Epiphania Selected Excerpt on Hama The Neolithic of the Levant -- Neolithic 3 Hama: Pages 304-305 (1978) A.M.T. Moore -- Oxford University A tell (mound) site on the River Orontes in Syria which has produced evidence of occupation from the Early Neolithic to circa 1400 A.D. Danish excavations in the 1930s revealed a fine palace of the Aramaean Period. The city has a long history having been settled as far back as the Bronze Age and Iron Age. In the 2nd millennium B.C. it was a center of the Hittites. As Hamath it is often mentioned in the Bible where it is said to be the northern boundary of the Israelite tribes. The Assyrians under Shalmaneser III captured the city in the mid 9th century B.C. Later included in the Persian Empire it was conquered by Alexander the Great and after his death (323 B.C.) was claimed by the Seleucid kings who renamed it Epiphania after Antiochus IV (Antiochus Epiphanes). The city later came under the control of Rome and of the Byzantine Empire ...

(2) The Danish Excavations at Hama on the Orontes by Harald Ingholt During the years 1931-38 a Danish archaeological expedition sponsored by the Carlsberg Foundations of Copenhagen in Denmark, worked in Syria. The site chosen was Hama on the Orontes -- the Old Testament Hamath. The ancient city site, situated in the northern outskirts of modern Hama, forms a most imposing mound about 336 metres long -- 215 metres wide and 46 metres high. Twelve different levels of civilization were uncovered ranging in time from the fifth millennium to about 1400 A.D. and yielded rich material for the reconstruction of the ancient history of the city. Not only did the mound furnish ample evidence of the types of pottery used by the Hamiotes during the long life of their town but terracottas -- objects of stone and of bone -- bronzes -- ivories -- glass -- seals -- sculptures and mosaics were brought to light in different levels, each helping to shape the face of the civilization in which it was found.

On excavated sites in Syria there is a marked lacuna from about 1750-1600 B.C. and the same holds true of Hama. A sparse level (Hama Level G) characterized by thin and elegant pottery forms can be dated to about 1550-1450 B.C. and then another gap intervenes, lasting until the beginning of the Iron Age about 1200 B.C. At this time warlike tribes from the North and the west, the so-called Sea Peoples, equipped with powerful weapons of iron, emigrated from their usual habitat to win for themselves new homes in the fertile lands to the South. They must early have established themselves in Hama where they reigned supreme until ousted sometime during the tenth century by another wave of conquering tribes, the Aramaeans. The Sea peoples burned their dead and actually more than 1100 cinerary urns have been found in Hama deposited in the area below and south of the mound and brought to light by the expedition under modern courtyards and houses (Hama Level F).

Beside a small number of cuneiform tablets several Aramaic graffiti came to light; also some fragmentary inscriptions in Hittite hieroglyphs and a few graffiti in characters recalling those of the “Phrygian” inscriptions recently found as far north as Bogazköy. After Sargon’s wholesale destruction of the city centuries were to pass before a new town or quarter of the town rose again on the mound. In Hellenistic times, under Antiochus Epiphanes, the mound was again inhabited and continued to be so through Roman and Byzantine times until the city was taken by the Moslems in 650 A.D. The latest level, the Arabic (Hama Level A), was in a way disappointing as its average depth was between 3 and 4 meters, through which one had to dig before arriving at earlier levels. In return it yielded however an extremely rich and varied series of unglazed and glazed pottery and glass; a few pieces imported from Europe -- Persia or China but most of it made in Syria itself. The detailed chronological study of this material is of great promise thanks to the many coins found in this level. According to them the mound seems to have been occupied in Moslem times from about 950-1400 A.D. but the floruit of the level was in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries and it is to these centuries that the majority of the Arabic finds belong ...

(1) The Danish Expedition to Hama Harald Ingholt (1931-38) National Museum of Denmark

(2) The Danish Excavations at Hama on the Orontes by Harald Ingholt

|

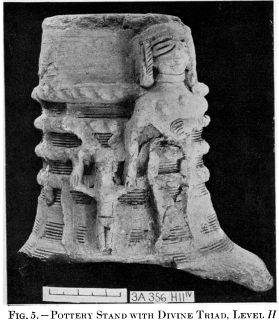

During the years 1950-1750 B.C. the city enjoyed a period of steadily rising prosperity

to judge from the wealth of pottery and other finds excavated, not only on the

mound but also below the hill in rock-cut tombs. The favorite kind of pottery was

now the carinate bowl together with vessels decorated with incised or notched lines

or bands in relief. A divine triad of goddess -- child and god figures in relief on a pottery

stand (figure 5) and numerous flat-backed terracotta figurines give us evidence of the

divinities worshipped in this period. The gods seem mostly to be represented seated

During the years 1950-1750 B.C. the city enjoyed a period of steadily rising prosperity

to judge from the wealth of pottery and other finds excavated, not only on the

mound but also below the hill in rock-cut tombs. The favorite kind of pottery was

now the carinate bowl together with vessels decorated with incised or notched lines

or bands in relief. A divine triad of goddess -- child and god figures in relief on a pottery

stand (figure 5) and numerous flat-backed terracotta figurines give us evidence of the

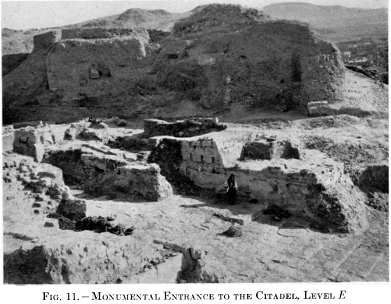

divinities worshipped in this period. The gods seem mostly to be represented seated  The Aramaeans, who succeeded the Sea peoples in Hama, were Semitic tribes

from the desert. For about 200 years they ruled over the river town, a period

marked by great material achievement and more military power than at any other

time in its history (Hama Level E). In 790 B.C. however the

The Aramaeans, who succeeded the Sea peoples in Hama, were Semitic tribes

from the desert. For about 200 years they ruled over the river town, a period

marked by great material achievement and more military power than at any other

time in its history (Hama Level E). In 790 B.C. however the