|

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) The Wadi Ghazzeh (Wadi Gaza) in Israel Updated September 17th 2019

Petrie in the Wadi Ghazzeh and at Gaza: Harris Colt’s ‘Candid Camera’ https://ancientneareast.tripod.com/PDF/james1979.pdf https://doi.org/10.1179/peq.1979.111.2.75

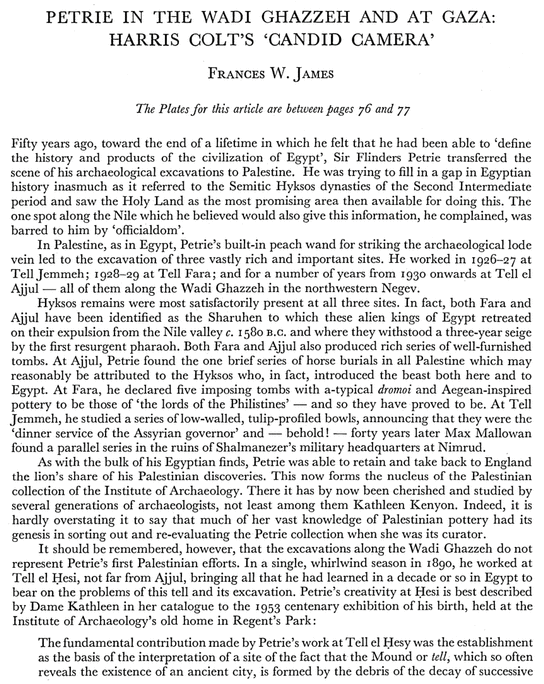

Fifty years ago, toward the end of a lifetime in which he felt that he had been able to 'define the history and products of the civilization. of Egypt', Sir Flinders Petrie transferred the scene of his archaeological excavations to Palestine. He was trying to fill in a gap in Egyptian history inasmuch as it referred to the Semitic Hyksos dynasties of the Second Intermediate period and saw the Holy Land as the most promising area then available for doing this. The one spot along the Nile which he believed would also give this information, he complained, was barred to him by 'officialdom'. In Palestine, as in Egypt, Petrie's built-in peach wand for striking the archaeological lode vein led to the excavation of three vastly rich and important sites. He worked in 1926-27 at Tell Jemmeh; 1928-29 at Tell Fara; and for a number of years from 1930 onwards at Tell el Ajjul -- all of them along the Wadi Ghazzeh in the northwestern Negev. Hyksos remains were most satisfactorily present at all three sites. In fact both Fara and Ajjul have been identified as the Sharuhen to which these alien kings of Egypt retreated on their expulsion from the Nile valley circa I580 B.C. and where they withstood a three-year seige by the first resurgent pharaoh. Both Fara and Ajjul also produced rich series of well-furnished tombs. At Ajjul Petrie found the one brief series of horse burials in all Palestine which may reasonably be attributed to the Hyksos who in fact introduced the beast both here and to Egypt. At Fara he declared five imposing tombs with a-typical dromoi and Aegean-inspired pottery to be those of 'the lords of the Philistines' -- and so they have proved to be. At Tell Jemmeh he studied a series of low-walled tulip-profiled bowls, announcing that they were the 'dinner service of the Assyrian governor' and -- behold! -- forty years later Max Mallowan found a parallel series in the ruins of Shalmanezer's military headquarters at Nimrud. As with the bulk of his Egyptian finds, Petrie was able to retain and take back to England the lion's share of his Palestinian discoveries. This now forms the nucleus of the Palestinian collection of the Institute of Archaeology. There it has by now been cherished and studied by several generations of archaeologists, not least among them Kathleen Kenyon. Indeed it is hardly overstating it to say that much of her vast knowledge of Palestinian pottery had its genesis in sorting out and re-evaluating the Petrie collection when she was its curator. It should be remembered however that the excavations along the Wadi Ghazzeh do not represent Petrie's first Palestinian efforts. In a single whirlwind season in 1890 he worked at Tell el Hesi, not far from Ajjul, bringing all that he had learned in a decade or so in Egypt to bear on the problems of this tell and its excavation. Petrie's creativity at Hesi is best described by Dame Kathleen in her catalogue to the 1953 centenary exhibition of his birth, held at the Institute of Archaeology's old home in Regent's Park:

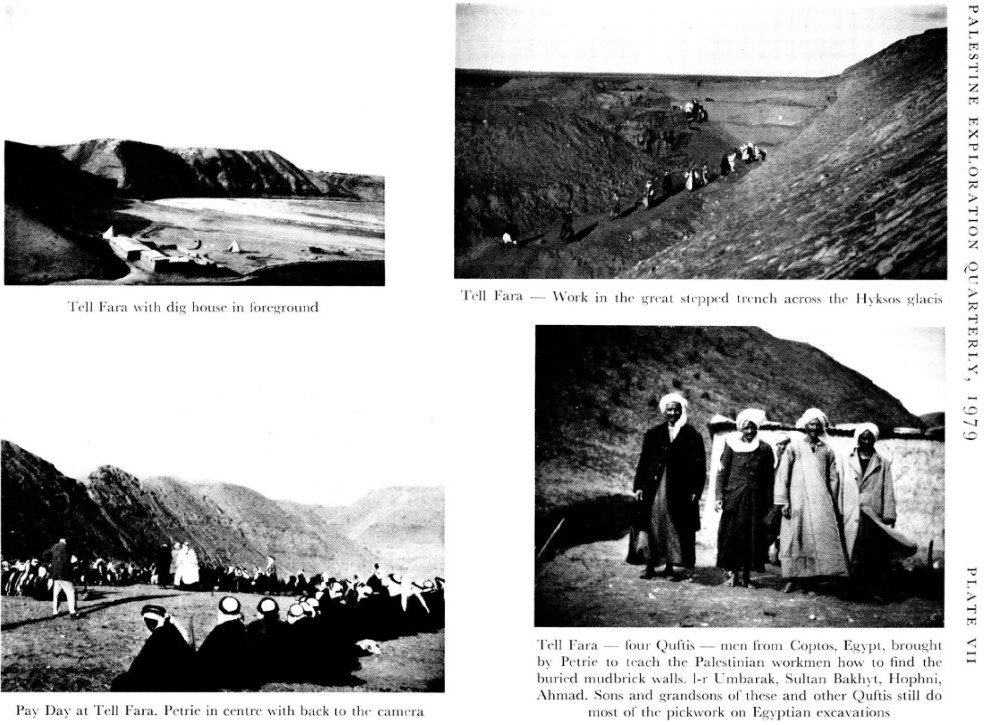

The fundamental contribution made by Petrie's work at Tell el Hesy was the establishment as the basis of the interpretation of a site of the fact that the Mound or tell, which so often reveals the existence of an ancient city, is formed by the debris of the decay of successive building stages; a fact so obvious nowadays that one forgets that it was not always recognized. But in the publication of Tell el Hesy one finds Petrie's original enunciation of this thesis, for the acceptance of which with reference to Troy Schliemann was still struggling. From the recognition of this basic fact gradually arose the development of stratigraphical excavation in Palestine. Among those present on Petrie's 20th century Palestinian digs were a number of the Quftis -- the special group of workmen from Coptos whom he had trained to find the buried mudbrick walls. By the I930's several generations of Qufti fathers must have passed this knowledge down to their sons (as they still do) and so were taken along to Palestine to pass their know-how on to the local Beduin. Lady Petrie joined the work on most of the seasons while slightly differing groups of 'Petries' students came each year. Many if not most of the latter we know today as leading scholars in one or another field of Near Eastern studies. They include the late James Starkey who excavated Lachish; Olga Tufnell who published Lachish; and the late Lankester Harding, formerly Director of Antiquities in the state of Jordan and an expert on Safaitic studies. Also among Petrie's students were Harris Colt and his first wife Theresa. They do not seem to have·been at Jemmeh but dug at Fara and on several of the Ajjul seasons. Mrs Theresa Colt's death discouraged her husband from continuing active field work though Palestinian archaeology owes perhaps even more to him for his later initiation of the Colt Institute series of archaeological publications. |