|

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) Neolithic Hauran Overview: Auranitis (Hauran) (Arabic Ḥawrān) also spelled Hawran -- Houran -- Horan is a volcanic plateau, a geographic area and a people located in southwestern Syria and extending into the northwestern corner of Jordan (1) ...

Selected Excerpt on Hauran

The Neolithic of the Levant (1978) A.M.T. Moore (Oxford University)

Chapter 4: Neolithic 2 Hauran (Page 208) One surface station in the Hauran has yielded a collection of 13 blades. They were all large and unretouched with narrow rounded bulbular ends characteristic of platform preparation on double-ended cores. They may tentatively be attributed to a Neolithic 2 site although the exact location of their findpoint is not known. There is insufficient evidence to assign the site to any regional group ... (2) Five Years in Damascus: including an account of the history topography and antiquities of that city : with travels and researches in Palmyra Lebanon and the Hauran -- Volume 2 by Josias Leslie Porter (1855) PDF

... I had already spent three years in Syria before an opportunity occurred of carrying out my intention with regard to the Hauran. I was hindered in part by the calls of duty and in part by the disturbed state of the country ; yet still my desire remained strong as ever and was even increased by a more minute study of those sketches of its history and geography contained in ancient writers. The breaking out of the Druze war in the autumn of 1852 took away all hope of visiting it for a lengthened period ; but the defeat of the Government troops and the consequent desire for peace on the part of the Sultan again seemed to open my way. Mr. Wood, the British consul at Damascus, was requested by the Pasha to act as mediator after the representatives of some other European nations had volunteered their services and failed. This tended to increase the great influence he had formerly possessed with the Druzes, the dominant party in the Hauran. He arranged a meeting with Sheikh Said Jimblat, the most powerful and influential of all the Druze chiefs ... The sheikhs of the Hauran all assembled to receive the proposals of the Government and discuss the terms of peace. It was a stormy scene ; and more than once a peace congress was well-nigh changed into a fierce battle. The fanatical Muslems (sic) feared or pretended to fear treachery on the part of Mr. Wood and Said Beg and once the cry was raised to pull down the house in which they were sitting. The proud Druze chief could ill brook such insults and haughtily stated that if he had anticipated such insolence he would have brought from his native mountains such a force as would have effectually prevented its recurrence for the future. In fact, it was only the smallness of his retinue — about a hundred and fifty men — that prevented him from taking instantaneous revenge. Still, notwithstanding such threats and insinuations on the spot and no less dangerous intrigues of disappointed consuls in Damascus, Mr. Wood with his usual ability succeeded in opening up communications which have secured a long truce and promise to effect final reconciliation and peace. Mr. Wood, on his return to Damascus, assured me of the practicability of a journey to that province after the feelings of the people had quieted a little and the bandits, whom war ever draws toward it, had withdrawn to some other quarter ... Toward the close of January 1853 an American gentleman arrived in Damascus and expressed his determination to visit the Druzes of the Hauran ; and I at once agreed to accompany him. The Rev. Mr. Barnett also expressed his desire to join our party. Mr. Wood kindly favoured our proposed journey and promised us strong letters of recommendation to the five principal Druze sheikhs. The great difficulty now was to get to the Druze district. A blood feud existed between the Kurds and the Druzes ; and the former, being irregular troops in the pay of the Government, were scouring the plain of Damascus attacking and murdering little parties of Druzes wherever they could find them. This blood feud prevented the Druzes from approaching the city of Damascus ; and hence our difficulty in obtaining an escort to the borders of their territory. The kindness of Mr. Wood again aided us. Mr. Misk, his dragoman, came to me on Saturday the 29th of January bringing with him a Christian, an inhabitant of the village of Hīt in the Jebel (mountain area of) Hauran. He informed us that a large caravan was to leave the city on Monday for his native village taking the direct road by Nejha and along the eastern border of the Lejah. This was the route which of all others I preferred to travel. Commencement of the Jebel Hauran ... After twenty minutes delay an old man rode up to us and directed us in the road to Hiyat. The road we were directed to follow led south by east up the easy slopes which are here bleak enough; not a tree or a shrub to diversify the naked scenery. The soil is extremely fertile ; but as the basaltic rock occasionally crops over it and large boulders and broken fragments lie scattered thinly over its surface, the whole has a ragged and forbidding aspect. And there were no grand features to relieve the monotony. The mountain summits in front were concealed by the heavy drifting clouds. After ascending about three-quarters of an hour and surmounting a little eminence we began to observe the first signs of modern cultivation ; and we also obtained our first view of the village of Hiyat standing upon the hill side above us like a huge fortress. On our left also we saw several castle-like villages, some on the summits of tells (mounds) and others at their bases. The signs of life and industry now appeared in the fields on every side. Numerous yokes of oxen were engaged in turning up the fertile soil with ploughs which are no doubt exact counterparts of those used in the days of the patriarchs and by the subjects of the mighty Og, whose ancient kingdom we were traversing.

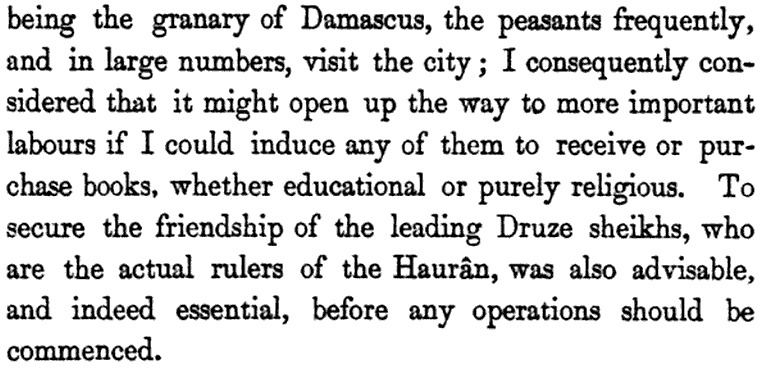

At 8-30 we reached the village of Hiyat and rode at once to the sheikh's house where we were received with great distinction. We simply announced ourselves as Englishmen and this was sufficient to open to us the heart and home of the noble Druze. Coffee was produced, roasted, pounded and presented with all due formality .... I now expressed a desire to see the various ruins of the village ; and a young Druze offered to act as my guide.

Hiyat is built on the gentle slope of the hillside in the form of a quadrangle and is somewhat less than a mile in circumference. The houses are all constructed of roughly hewn stones, uncemented but closely jointed. They are massive and simple in their plan, giving evidence of remote antiquity. The present inhabitants have selected the most convenient and comfortable chambers and in these have settled down without alterations or additions. The roofs are all of stone like those of Buråk and so also are the doors ; but I observed in one or two places that the stone doors had been removed and wooden ones substituted. There is no structure in the village with any pretension to architectural beauty ; but on the eastern side near a large tank there are ruins with fragments of ornamented cornices and pediments : these are now so completely destroyed that it is impossible to ascertain even the plan of the original building ... I estimated that about one-half of the houses in this village still remain perfect or nearly so and quite habitable ; but not more than a fourth of these were occupied at the time of my visit. On returning to the sheikh's house after a brief inspection of the ruins, I found that our servants had arrived and that a horseman had also come from Sheikh Ass'ad of Hīt to conduct us to his residence where our companion was comfortably installed.

Leaving this interesting ruin we rode up the hill-side through fine grain fields to Hīt, which we reached in half an hour. We were led immediately to the house of Sheikh Ass'ad 'Amer, who received us with every demonstration of respect and welcome, having come out to the gate of his courtyard to meet us. We were ushered into the reception room, a mean half-ruinous and dirty apartment where a crowd of villagers and others were assembled. The massive stone roof was supported by antique columns and in the centre of the floor was a square hearth sunk about six inches below the rough pavement. Here blazed and crackled an immense fire of charcoal. There was no opening or chimney above to let out the volumes of smoke but in the midst of the blazing mass was a huge bar of iron which was intended to prevent any deleterious effects from the fumes of the charcoal. I presented our letter of introduction and the sheikh, after reading it and seeing coffee properly served, left the room. In about half an hour he returned and invited us to another apartment in the harim which had been prepared specially for ourselves. Here we found comforts such as we had not anticipated. The floor and divans of the spacious apartment were covered with rich Persian carpets and cushions of embroidered velvet were arranged against the wall, while three immense mankals of blazing charcoal diffused an agreeable heat through the chamber. A plentiful repast of honey, dibs, butter and various kinds of sweetmeats were served up soon after our entrance and at sunset a feast was prepared for us which far surpassed anything of the kind I had before seen. A whole sheep roasted and stuffed with rice, graced the centre ; beside it was a huge dish of pillau, some three feet in diameter. Around these were arranged nearly twenty other dishes of various kinds of dainties including fowls, soups, kibbeh, burghul and a host of others. Round these again were arranged the thin cakes of bread in little piles, on the top of each of which was placed a wooden spoon, the only instrument used in this primitive land in taking food.

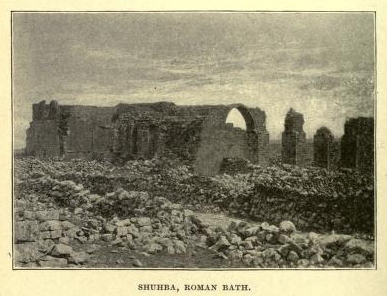

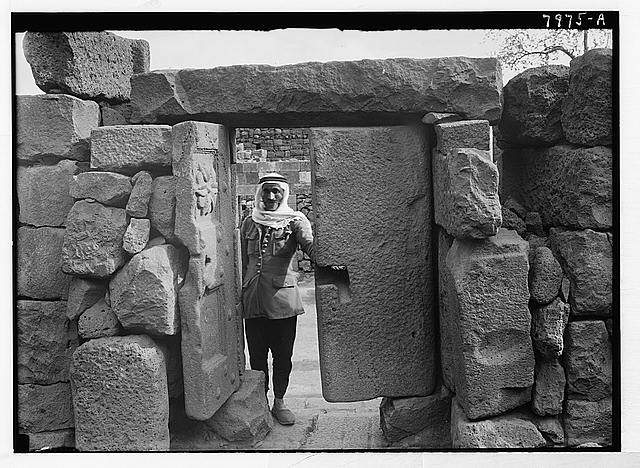

The village (Hīt) is about a mile and a half in circumference and the general character of the architecture is similar to that of Hiyat. Many of the ancient streets in Hīt can be traced, notwithstanding the masses of ruins and rubbish that have accumulated in them during the course of ages. They are narrow and tortuous and thus bear a marked contrast to those of other towns in this region which are manifestly of Roman origin or at least were reconstructed in the Roman age. The houses are all massive and simple in plan with stone roofs supported on arches and stone doors. Some of the latter are finely panelled and otherwise ornamented with tasteful mouldings. Foot Note: In this town a large majority of the houses are mere heaps of ruins ; many however are still nearly perfect and the present inhabitants occupy exclusively ancient dwellings. At Hīt there is no fountain of living water but in the centre of the town is a spacious tank for collecting rain water during the winter. There is besides, we were informed, a subterranean aqueduct coming from the mountains toward the south which still conveys sufficient water for the domestic uses of the inhabitants. Beyond the walls is a large subterranean reservoir and from this small canals formerly conducted the water to each of the principal houses. We did not see any of these works but we drank of the water and found it excellent and we were assured that even during the heat of summer it is cold as ice. It is generally believed that the source is somewhere in the distant mountains but I think the water is collected in the same way as many of those streams which are now seen in the plain of Damascus, by a canal carried along for several miles at a little depth beneath the surface. Due south from Hīt, about ten miles distant, a lofty conical peak shoots up over the surrounding hills and forms a prominent object in the landscape. It is called Tell Abu Tumeis and is one of the highest summits in the Jebel Hauran. Our kind host used every effort to persuade us to spend the day with him but when he saw that we were determined on proceeding he sent with us his nephew and another horseman to serve as both guide and guard of honour; while he himself stated that he would ride direct to Shuhba and acquaint his brother Fares of our intention to visit him. We ordered our servants to accompany him with the baggage as we wished to make a long detour in order to visit the ruins of Bathanyeh and Shuka. At 11-10 we rode out of the court-yard amid the salams and prayers of the assembled villagers and proceeded across the fields in a direction about north-east straight towards the ancient town of Bathanyeh. The soil in this region is of unrivalled fertility and the wheat is celebrated as the finest in Syria. The fields were already green with the new crop, which was springing up with a luxuriance seldom seen in other parts of Syria. In several places I observed traces of an ancient road with large sections of the pavement still remaining and the foundations of walls along each side. The day was bright and cool, the turf firm and smooth, our horses fresh and our own spirits high; the effect of the hearty welcome we had received and the magnificent and interesting country around us. Our new companions too were eager to display the metal of their fine steeds and their own skill in horsemanship ; so giving rein to our horses, we dashed across the slopes and soon reached Bathanyeh. The distance from Hīt is about an hour but in less than half that time we accomplished it. Bathanyeh is situated on the northern slope of the Jebel Hauran, commanding an extensive view to the north and north-west. About an hour below the town the gentle declivity terminates in a plain which stretches away to the lakes of Damascus and the Tellul ... Bathanyeh is not quite so extensive as Hīt ; but the buildings are of a superior style of workmanship and in better preservation. So far as I am aware no traveller has ever before visited this ancient site or even referred to its situation and importance as tending to identify the ancient province of Batanaea. On entering the town we first passed along a paved street to a large building with a square tower some forty feet in height beside the entrance. The spacious gateway was shut by massive folding-doors of stone ; but we threw them open with ease and entered a large flagged court-yard, in part covered with ruins. Around this were the apartments, each opening into it by stone doors, thus resembling the plan of a modern Damascus mansion. There are no public buildings of any extent or pretensions to architectural beauty standing ; but there is evidence of comfort and wealth in almost all the private dwellings. Durability and simplicity appear to have been the only objects aimed at by these utilitarian architects; and they have succeeded so well that though their land has been long deserted and their city long forsaken; and though the name and the history of the former inhabitants have for centuries been forgotten and unknown; yet these mansions remain as their only memorials. Such is the situation and such the character and state of the buildings in Bathanyeh. There can be no doubt that we have here preserved in modern days the name of the Roman province of Batanaea and the Syrian kingdom of Bashan. It is quite true that both these ancient names were given to provinces or sections of country ; but it is also true, as I shall show, that there was in that district an important town of the same name. At present there is a province called Ard el-Bathanyeh --- " the country of Bathanyeh" --- embracing the whole of the mountain-chain called Jebel Hauran with a section of the plain on the northern and eastern sides. This district is now universally called by the natives either Ard el-Bathanyeh or Jebel el-Druze ; the name Jebel Hauran is only applied to it by strangers. Batanaea is frequently mentioned by ancient writers as a province but down to the Christian era we have no notice of a city of that name. In the Notitia Ecclesiastica however Batanis is one of the thirty-four ecclesiastical cities of the province of Arabia, whose bishops were suffragans of the primate of Bostra; and it can scarcely be doubted that Bathanyeh is the place there referred to. By the early Arabian geographers, Bathanyeh is mentioned both as a city and a province but no details are given of it. Turning away from these interesting remains, we rode across the fields in a direction a little east of south towards a small conical hill called Tell Azran. Having surmounted a gentle swell on the eastern side we came in sight of the ruins of Shuka, the ancient Saccaea; and in a quarter of an hour more were beside them. From Bathanyeh to Shuka is about four miles. There is a gentle ascent as far as the Tell Azran ; but the remainder is level. In several places are traces of an ancient paved road. This town is built on the side of an extensive plateau which surmounts the slopes of Hīt and Bathanyeh and extends eastward as far as Juneineh, one hour distant. Immediately on entering Shuka I climbed to the summit of a square tower to gain a general view of the whole town and the surrounding country and to take bearings of all the prominent objects in view. The ruins I estimated at about two miles in circuit. Few of the buildings are in a good state of preservation but some of them exhibit marks of considerable taste and skill in architecture. The lines of most of the streets can be traced, though now encumbered with ruins ; they are narrow but straighter and more regular than those of Hīt or Bathanyeh. ... I proceeded over ruinous houses and narrow streets toward that part of the town now inhabited. The stones have here been cleared away from the centre of the streets to form a path for animals and similar paths have also been made through the rubbish that encumbers a few of the ancient courtyards. The present inhabitants -- Druzes --have taken possession of such chambers as had their roofs and doors perfect ; but I did not observe anywhere a new erection or even recent repairs ; indeed this would be quite unnecessary for there are far more houses still habitable than there are people to occupy them. ... At 2-40 we again mounted and rode over a rocky swell into the fertile plain through which we dashed at a hard gallop towards Shuhba, now visible on the summit of a ragged ridge. Our course was first through fresh ploughed fields till we reached the regular path. Here again are traces of an ancient road. After riding about two miles we saw on the ridge of the mountains -- two hours' distant on the left -- a ruin resembling a castle; our attendants had forgotten its name but pointed out, on a conical peak below it, the village of Tufhah ; and they informed us that in the wady, half an hour farther east, is Nimreh. A deep and wild ravine commences a little eastward of the latter place and runs in a western direction past Tufhah to Shuhba. We could now clearly see its course beyond the swelling ground on our left hand and from Shuhba I ascertained its true direction. This ravine divides the acclivities of Hīt, Bathanyeh and Juneineh from the lofty mountains on the south. The main chain rises up abrupt and rugged on its southern bank and the scenery here becomes bolder and more picturesque, the hill-sides and wild glens between being generally clothed with forests of evergreen oak. Crossing the ravine we reached Shuhba, situated on its southern bank. The distance of this place from Shuka is eight miles and a half but we accomplished it in an hour and three-quarters. We scrambled over the ruined wall beside a fine Roman gate and after watering our horses at a large tank, partly filled with muddy water, we proceeded along a well-paved ancient street to the residence of the sheikh ... Selecting an intelligent guide we thence ascended to the summit of Tell Shuhba. The ascent, though not long, was difficult and toilsome owing to the deep coating of small black stones intermixed with porous lava and light tinkling cinders, with which the whole hill-side is covered.

It is singular that we possess no historic record of a city of such extent and whose buildings were so costly and displayed so much of architectural skill and taste. It is just one of the many in this interesting district which have come down to us without a name or a story. A diligent search amid its wide-spread ruins might yet bring to light its name on some inscribed tablet ; and it is to be hoped that some enterprising traveller with the means and the time at command will ere long undertake the thorough examination of the ruined and deserted cities of Bashan. ... Everything being now arranged for continuing our route we set out accompanied by our new muleteer Yusef, a Christian from Lebanon and our servants, well mounted upon strong mules, which had been captured by our host Sheikh Fares during the late war. Passing over the ruined wall, here almost completely prostrate, near the site of the west gate, we turned to the left along its side and then descended by a difficult and rocky path into the ravine at the south-west angle of the city. We now followed the line of an ancient road between Tell Ghurarah and the mountains, in a course a little west of south, about twenty minutes from the plain. The soil between the rocks is deep and rich ; and the whole slopes seem admirably adapted for the cultivation of the vine and the olive. Now however there is not a tree to be seen planted by man. In forty minutes we reached a shallow rocky glen in which, a few minutes on our left, we saw the ancient village of Murduk ; and a little north of it on the summit of a ridge, a white-domed wely (mountain range). In 1 hour 35 minutes from Shuhba we reached the ruined town of Suleim, situated on a low tell on the border of the plain. As soon as we halted I ascended to the top of the first building we came to --- a beautiful temple --- and there had time and opportunity to examine the country and take bearings. The town of Suleim is about a mile and a half in circumference and contains the remains of some large and important buildings ; but most of them are now mere heaps of ruin. The structure on the top of which I stood is one of great beauty. It is some distance from the town, on the north side ... After some time spent in climbing over heaps of ruins, now mere confused masses, we reached the house of the Sheikh and were received with much courtesy. He pressed us to enter his house and take coffee and said he had sent his brother to invite us ; but we expressed our regret that we were in such haste to reach Kunawat that we could not possibly stop.

On returning to the temple we found that our Druze guide had arrived from Shuhba, having waited for letters ... We examined some large and curious caverns in front of the temple. They are about 30 feet deep and the roof is supported by strong arches, the walls being in some places the natural rock and in others built up of roughly hewn stones. They extend a considerable way underneath the surface. They may have been intended for tanks or more probably for grain-stores in times of danger. We had seen similar but smaller ones at Hīt and Bathanyeh. All the ancient writers who describe this country speak of the great caverns with which it abounds ; but of these more will be said in the sequel. At 2-25 we mounted our horses and rode off amid the salams of a large crowd of Druzes who had collected round us. We were led by our new guide Mahmud, an athletic and determined-looking Druze. He was armed with sword and pistols but had neither spear nor gun and rode a splendid grey charger.

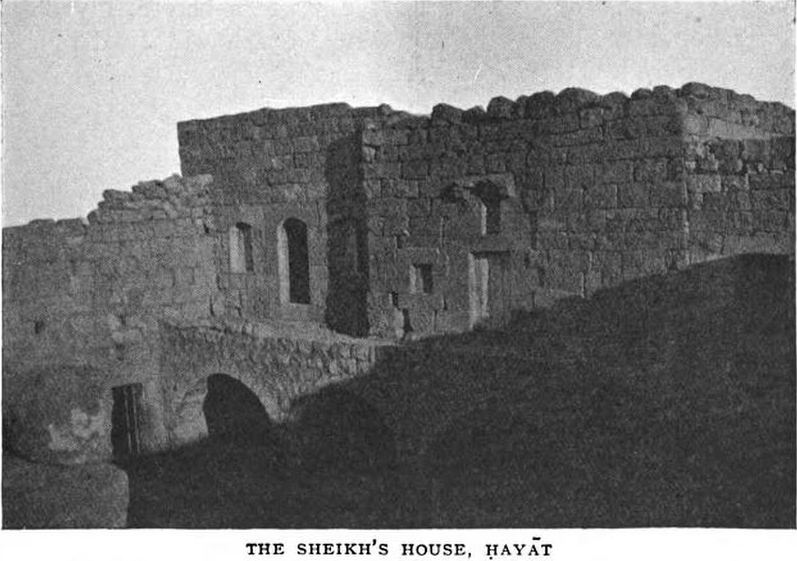

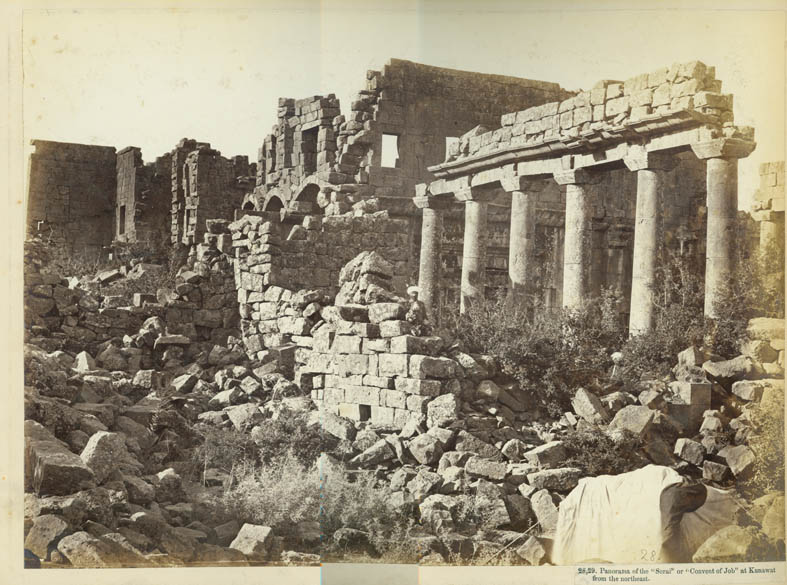

Our road led us up the easy slope of the mountain towards Kunawat ... Along the side of our path there were distinct traces of a Roman road, the pavement in some places remaining entire. We observed it at various points between Suleim and Kunawat. The scenery here becomes picturesque and beautiful. The mountains have bolder features and the valleys and ravines are clothed with evergreen forests while the grey ruins of towns and villages appear on every side. In twenty minutes we reached the side of the deep ravine on the southern bank of which the city is built and, crossing it by a modern bridge, we rode up a well-paved road to the ruined gate. A few yards beyond this we entered the court-yard of the sheikh, where we met with a welcome reception. After the salams and the " thousand and one " wishes and prayers for our health and happiness, the never-failing coffee was prepared and presented. After these necessary ceremonies I proposed a walk among the ruins. The sheikh immediately offered himself as a guide but not less than twenty others followed in his train. Kunawat is built on the left bank of a deep and wild ravine. I estimated the extreme length of the city at about a mile and the breadth nearly half a mile.

After leaving the sheikh's house we walked up a street along the brow of the ravine ; the ancient pavement is in excellent preservation. On the right are ruins of large private houses, solidly and elegantly built. The stone doors especially attracted my attention as most of them are panelled and have ornamental mouldings while a few are adorned with wreaths and fruit in bas-relief. I observed an ancient aqueduct running parallel to the street. This must have been a favourite quarter with the chief men of the city for the private mansions appear to have been all spacious and expensively built. The situation too is attractive—the wild ravine lying below with its foaming torrent dashing over a rocky bed and its theatre and temple ; and the castellated heights above, over which rose up the graceful wooded summits of the hills of Bashan. ... The worthy sheikh here took me by the hand and led me to a broken place in the pavement and there pointed down to what he considered an object of no small curiosity. This opening showed that the whole space under our feet was one series of vaults supported on pillars and arches. This was evidently a vast reservoir to which water was carried during winter from the wady higher up the mountains and hence led by ducts and canals to every part of the upper city. ... The sheikh pointed with a beaming countenance to a ruin before us (A). It is a small temple of fine proportions and admirable workmanship occupying a site well fitted to exhibit its beauty to the fullest extent. (A) A sketch of this temple is given at the head of Chapter XI (Above) ... We now returned to the sheikh's house well pleased with our walk. The evening was spent in lively conversation in which some of the chief men in the village took part. The sheikh is a man of superior sagacity and intelligence ; he asked eagerly about European manners and appeared delighted with descriptions of railways and electric telegraphs. From mechanics the conversation turned to politics and now the sheikh, who sat beside me, assumed a low and confidential tone and plied me with questions innumerable as to the intentions of the government about the conscription and the renewing of the war. I told him my private opinion was that the war would not be resumed and that the conscription, in so far as they were concerned, had been abandoned ... The first mention we have of Kenath in the Bible is when the Israelites subdued Og King of Bashan and took possession of his kingdom; it is then said that "Nobah went and took Kenath with the villages thereof and called it Nobah, after his own name."

officer of Ibrahim Pasha's army during the Diuze war but that it had been bruised and broken in the conflict. Time and rough usage had now dimmed and scratched the glasses and he wished to obtain another like it. I promised to try and procure one for him if he would come to me at Damascus. My dragoman Nikola now endeavoured to persuade him to accept of some remuneration for the expense he had been put to in feeding ourselves, our servants and our horses; but he absolutely refused to take a single para ! We resolved not to leave without paying for our entertainment in some way and when the sheikh refused, Nikola gave the bakhshish to the old man who presided at the coffee. At 1-30 we left Kunawat and, sending our servants by the direct road, we rode up to the left to revisit the ancient tower-tombs. The buildings are square and are divided by string-courses into two and three stories. The doors and windows are very small and within are stone recesses for bodies similar to those at Palmyra. It is remarkable that Burckhardt found in this city an inscription in the Palmyrene character (Page 84 in Travels in Syria 1822).

... As we rode along the town of Atil was some distance on our right. This place was visited by both Burckhardt and Buckingham (Travels among the Arab Tribes 1825) and views of some of its ruins are given by Laborde. It is of considerable extent being larger than Suleim and it contains the remains of two fine temples. On the south side of the town is a temple of fine workmanship erected, according to an inscription copied by Burckhardt, in the fourteenth year of the Emperor Antonine -- A.D. 151. After an hour's ride from Kunawat we emerged from the oak forest upon an open and stony slope and saw the large city of Suweideh before us on the summit of a low ridge. A deep ravine separated us from its extensive ruins, on reaching the brow of which I gave our letter of introduction to Mahmud, to deliver it to the sheikh and thus inform him of our arrival. The deep ravine called Wady Suweideh runs down between this building and the city. The winter torrent that flows through it is spanned by a fine Roman bridge of a single arch. Crossing this we rode up the opposite bank along an ancient road to a large but shallow reservoir, on the far side of which the ruins commence. We rode at once to the sheikh's house but found that he was absent. Being ushered into the reception-room preparations were made for serving coffee. We proposed to take a walk among the ruins and the sheikh's son, a fine boy of some fourteen years, splendidly dressed with a silver-mounted dagger in his belt, undertook to be our guide ... Verily the destroyer has been long at work here ! We pursued our course winding among piled-up ruins;— ruins nothing but ruins and desolation and faded grandeur and present misery and filth met our view. The modern habitations are the lower stories of the ancient houses and the whole surface has become so deeply covered with the fallen structures that most of the people seem to be residing in caves. The ancient city was built on the summit and southern declivity of a long and narrow ridge. We now ascended a steep bank to the summit and here found an immense reservoir not less than one hundred yards in diameter and from thirty to forty feet deep. It is filled by means of a subterranean canal coming from the wady considerably east of the city. Around this are the principal habitations of the present residents. In the sides of the ravine are some caves which, we were informed, are large and difficult of access. From the top of the ridge we got a good view of the extent and character of the whole ruins. They are far inferior in interest to those at Kunawat but they are much more extensive. I estimated the circumferance at about four miles. A fine Roman road runs past the western end of the city : it is the continuation of that which comes from the ancient Phoeno (Phoenicia). There is no city in the Hauran, not even Busrah, that surpasses Suweideh in the extent of its ruins and yet, strange to say, no clue has yet been found to its ancient name : and there is no mention of it in history previous to the era of the crusades. I have already said that there can be little doubt it was an episcopal city and it was, therefore, probably one of those to which new names were given by the Romans when they were rebuilt or adorned ; but after the decline of the Roman power the old names were again resumed and the new forgotten. Suweideh has suffered more from time and the accidents of war than almost any other city in this region. It has been ruined and built; so that it is not possible to form any correct idea of its ancient state. Inscriptions found in it show that it was a nourishing town previous to the conquest of this province by the Roman general Cornelius Palma in A.D. 105 ; and likewise that it was celebrated for the extensive trade it carried on with other countries down to the middle of the fourth century. Suweideh has now been for many years the acknowledged capital of Jebel el-Druze and the residence of their principal sheikh. It is one of the most populous villages in this district. The Druzes and Christians here live on amicable terms but there are no Muslems. We left Suweideh at nine o'clock and rode down the stony slope in a direction S. 20° W. In seven minutes we had on the right a small building called Deir es-Senan, situated on a low mound ; and a few minutes afterwards we entered the plain of the Hauran which stretched away in an almost unbroken expanse to the base of Hermon. At 9-35 we passed the small village of Mujeidel, inhabited by a few families ; and here we observed about twenty minutes on the right another building called Deir el-Tureifeh. A heavy shower of rain and hail now began to fall and a strong wind blowing in our faces made us feel its full force. Several times my horse wheeled round and refused to advance against the bitter blast and cold rain ... We began to ascend an easy slope that leads up to a rocky hill, on the summit and southern declivity of which stands the large village of 'Ary, where we arrived at 10-40, being thus one hour and forty minutes from Suweideh. We had ridden fast and our servants were still far behind ; we consequently went up to the side of a castle-like building on the summit of the tell to await their arrival and obtain a good view of the country. The Druze sheikh however, with half a dozen of his retainers, was soon with us and carried us off by force to partake of his hospitality ... 'Ary was once a town of considerable extent, the ruins being above a mile in circumference ; but there are no buildings now remaining of any importance and there are no traces of wealth or splendour. In a ruinous mosk Burckhardt copied a fragment of a Greek inscription which is of no historical value, being merely the tablet of some family tomb. The ancient name of the place is unknown but it may possibly be identical with the Ariath of the ' Notitia Ecclesiastica '. The tell on which it is situated is in the plain and nearly an hour from the western base of the mountains.

(3) Page 530 in A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: Part II by This is now one of the most important villages in the Hauran and the residence of one of the most powerful Druze sheikhs, Ismail el-Atrash. He is justly celebrated as the bravest of a brave race; and though of an humble family his good sword, tried in many a hard fight with Bedawy and Osmanli (Ottoman Turkish), has enabled him to rank among the first in the land. Ary is situated on a low rocky hill about 2 miles from the foot of Jebel Hauran. It was once of considerable size, the ruins and the houses of the modern village occupying a space about 1 mile in circumference; but there are no remains of importance nor are there any traces of former wealth or splendour. This is most probably the ancient episcopal city of Ariath ... On the West lies a vast plain, the Auranitis of the Greeks and Hauran of Ezekiel 47:16-18 and the Hauran proper of the modern Arab; but sometimes called en-Nukrah “The Plain” in distinction from el-Jebel "The Mountain" and el-Lejah “The Retreat" ... We left Ary at 11-30 and having learned that our servants had gone on in advance, we set out at a rapid pace towards Mujeimir, which now appeared before us on the eastern declivity of a conical tell in the plain. We reached Mujeimir in twenty minutes ; the houses are all of stone and of considerable antiquity, like all the others in this region. We felt disappointed in not finding our servants here as we had been told they were awaiting us ; but we supposed they had followed the main road to Busrah which runs on the western side of the tell. We rode on without dismounting at 12-30 we reached the small village of Wetr. Some distance to the south-east we observed the much more extensive ruins of Ghussan on a tell. The vast plain southward now opened up before us, dotted thickly with deserted cities and villages. That broad black belt in front with the massive towers and battlements rising up in the midst of it intermixed with tapering column and minaret is Busrah.

Here we found our servants and sent them forward along the straight road to Busrah ; while we, turning a little to the right, galloped across some rich fields to a large and massive building called Deir Zubeir. We reached it in ten minutes. It is a square structure with thick stone walls and has probably been latterly used, as its name would seem to imply, as a convent. Around it are clustered a few houses with stone doors and roofs but the whole is now deserted. From hence we rode towards Jemurrin, lying between us and Busrah. Soon after leaving the Deir we struck the Roman road which has already been referred to as running in nearly a straight line from Suweideh to Busrah. The pavement is in some places quite perfect and the line of the road, extending across the fine plain as straight as an arrow, is clearly marked. Following the line of the Roman road for about fifteen minutes we reached the brow of the Wady Zedy, a deep narrow and rugged ravine. In the bottom is a small stream flowing lazily over its rocky bed. A fine Roman bridge of three arches here spans it, crossing which we rode up to the village. Jemurrin stands on a gentle eminence on the south bank of the Wady. It is of considerable extent and contains the ruins of some large and handsome buildings. A lofty square tower beside the bridge was the first that attracted our notice from its resemblance to the tombs we saw in Kunawat. Leaving Jemurrin we followed the road which leads thence to the eastern extremity of Busrah ; and a few minutes gallop brought us up to our servants. At 1-40 we stood beside the ruins. The whole distance from Ary is a little over six miles. Our first object was to procure a house or at least some apartment we could call our own for the approaching Sunday. Mahmud soon found a small room in the sheikh's house where our baggage was speedily stowed away and arrangements made for ourselves. We at once engaged the brother of the sheikh to guide us over the ruins. In form the walled city was almost rectangular; as nearly as I could estimate a mile and a quarter in length by about a mile in breadth. Without the walls -- on the east north and especially the west -- were large suburbs. A straight street intersects the city lengthwise ; the north and south walls are nearly parallel to this and the east and west at right angles to it. Another street crosses it at right angles at a point east of the centre ; and the most important buildings of the city were clustered round the intersection of these two streets. The lines of many other streets can still be traced and from these it appears the city was constructed with great regularity. The general plan reminded me of Shuhba.

... Passing over vast heaps of ruins we crossed the prostrate city walls and walked on to the castle. This building is of great extent and strength and the outer walls are still almost perfect. The masonry and plan somewhat resemble the Castle of Damascus and like it, it is encompassed by deep moats, the water for which can be drawn, by means of an aqueduct, from a large tank a little to the eastward. The only entrance is by a door on the east side in the angle of a deep recess; and the approach to it is by a paved road over the fosse ; but in ancient times there was doubtless a drawbridge. Underneath are immense reservoirs for water and vaulted magazines. From hence our guide conducted us to the south-western tower, which is the loftiest in the whole castle. The country on the south and south-east now opened up before me, dotted with ruined cities and villages. Among others I saw Um el-Jemal, the identity of which with the ancient Beth-Gamul, has been suggested; and there cannot be much doubt of the correctness of his supposition. The plain here extends to the horizon, unbroken by hill or mountain ; and the soil, so far as one can judge from the distance, is similar to that farther north, rich and fertile ; while the frequent ruins prove that it was at one time no less densely populated. A few families now reside within the walls of the castle ; and we were informed that during the spring season all the inhabitants of the place gather in here, that they may protect their flocks and their property from the nightly depredations of the Bedawin. Formerly a strong force of irregular cavalry was kept here by the Pasha of Damascus but now there is no garrison and the rapacious Bedawin roam freely over the fields of the poor peasants, who have to pay them black mail. Garrisons of a few hundred horse at this place would be sufficient to keep the whole Arab tribes of the desert in check and the fertile plain of the Hauran would then be made to yield one hundred fold its present produce of grain. But here, as elsewhere, the Turks manifest no regard either for the welfare of the people or the improvement of the soil. Busrah is almost deserted. Only some twenty or thirty families inhabit it, occupying the lower rooms of the ancient houses. As a city it has long ceased to exist ; it is now one vast field of confused ruins. The number of its inhabitants is decreasing every year ; and ere long the place must be entirely abandoned, for the desert tribes are fast encroaching on the domains of the settled cultivators of the soil. February 7th — Dark threatening clouds still shrouded the mountains and swept over the broad plain as we went out at an early hour to take a final glance at the ruins of Busrah. When I returned I found my companions with the horses and servants all ready, so we mounted at once and rode off amid the salams and good wishes of the sheikh and a crowd of retainers who had gathered round us. A liberal bakhshish had almost overcome Muslem fanaticism.

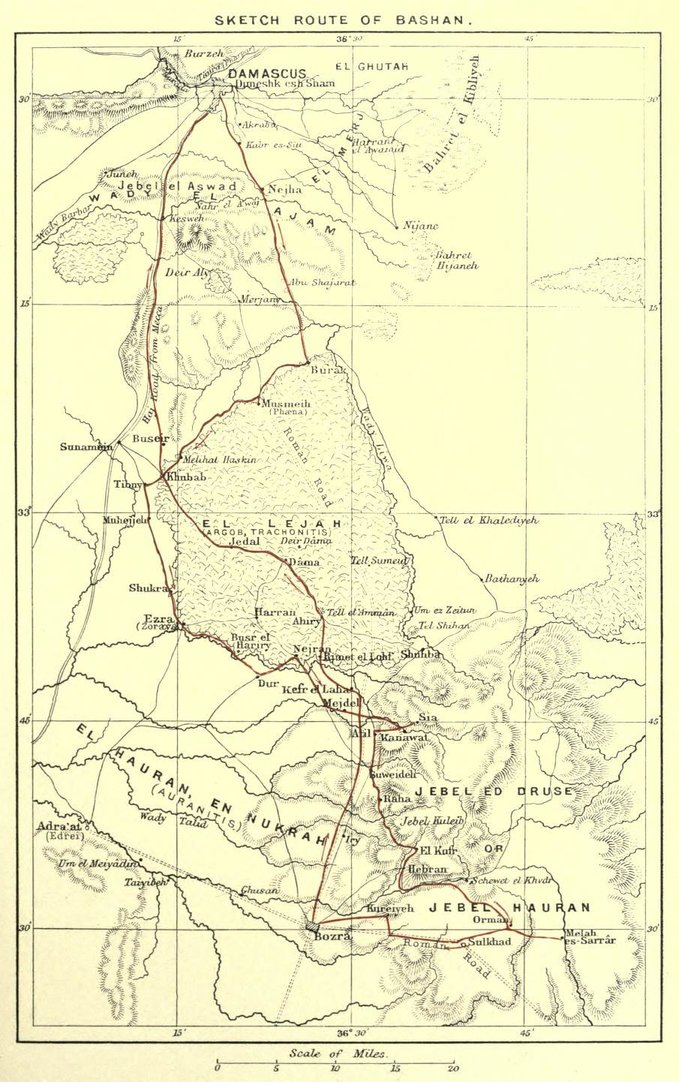

(5) A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: New and Revised Edition by ROUTE 34 --- TOUR IN THE HAURAN The Haurán is one of the most interesting sections of Palestine. For the number, extent and beauty of its ruins it far surpasses all the rest. Unfortunately it is not always accessible; and even when the traveller does obtain access he is almost constantly exposed to some sudden outbreak of fierce Muslem fanaticism on the one hand and to Bedawy ghuzus on the other: the latter throws a certain charm of adventure round the tour but the former is an absolute nuisance. A Druze escort is the best safeguard against both the one and the other. The Druzes are the dominant party in the Haurán. Without a safe-conduct from them it would be folly to enter the country. This however may be easily obtained through the British consul at Damascus. A couple of their sturdy retainers—well mounted, as they always are and well armed— form the best guards and guides. Some of them can usually be found in Damascus and if not the traveller may attach himself to a caravan and, provided with letters to the sheikhs, reach their territory. Another and perhaps a still better plan may be followed. After obtaining recommendations from the consul we proceed to the Druze village of Deir Ali, 4 hours from the city, whose sheikh will readily undertake to escort us across the intervening uninhabited plain to some of his brethren in the Lejah or the mountains. Between the territory of Damascus and the Druze district in the Haurán there is a broad desolate plain infested by Bedawy ghuzus from the eastern desert; and by robbers no less formidable from the rocky recesses of the Lejah. To pass this plain is our first difficulty, which may either be overcome by joining a caravan or under the escort of the sheikh of Deir Ali, a strong border chieftain. Once within the Druze district we have no difficulty in times of peace in securing as large an escort as may be desired for safety or show. The Druze sheikhs receive and entertain travellers with profuse hospitality and no compensation in money can be offered them. A bakhshish however in the shape of a few flasks of English gunpowder and a few boxes of first rate percussion caps, or a small telescope or better still, a good rifle is always acceptable. The Haurán is a generic name for a large district of plain and mountain ... It is now, as it was in Roman times, divided into 3 provinces; the Lejah, the Nukrah and the Jebel. The Lejah is a rocky plain of singular wildness, lying on the N.W. of the Haurán. It is extremely difficult of access owing partly to the nature of the country and partly to the character of the people. It is inhabited by a few tribes of Bedawin, lawless vagabonds and hereditary robbers. Their ancestors, in Josephus' days, were the pests of the whole country. Escorted by an influential Druze sheikh the traveller may, under ordinary circumstances, visit their wildest haunts. Though the region is filled with deserted towns and villages, the houses in many of which are perfect as when finished, these Arabs prefer their tents. Nukrah “the Plain" is the Haurán proper, the Greek Auranitis and the old Hebrew Hauran. It lies to the south of the Lejah and is one unbroken plain of the richest soil. It is the granary of Damascus and the most fertile region in Syria. Now, alas! it is sadly neglected, being periodically overrun by the vast hordes of the Anazeh who cover the country like locusts. It is literally filled with deserted towns and villages ... The villages of the Nukrah are principally inhabited by Muslems who in dress, manners and accent resemble the Bedawin. A few Christians live among them ; and the Druzes are also creeping over the plain from their home in the eastern mountains. Jebel “the Mountain” is the mountain district between the plain of Haurán and the eastern desert. Among the natives it still retains its ancient name Bathanyeh. The soil on the mountain sides is exceedingly fertile though often stony. To the artist and the antiquary this is by far the most interesting part of the country. The scenery is in some places beautiful and we meet with ruined towns every mile or two. Jebel is occupied almost exclusively by Druzes. There are however some small tribes of Bedawin who encamp amid the forests and make themselves useful as shepherds to their settled neighbours. There has long been a blood feud between all these tribes and the Anazeh. Having procured our letters of recommendation and Druze escort we are now ready to set out. We shall follow the eastern route which is not only the most direct but that usually taken by caravans of Druzes and Christians going to el-Jebel. ... On we march over a dreary treeless waste; the desert stretches to the horizon in bleak undulations with green grass and green weeds and a rich soil but with no habitation save the Arab tent and no occupant except the wandering Bedawy. Black masses of ruins stand here and there on tells, showing that desolation did not always reign here. A dark line is now seen running across the plain to the southward, like the shadow of a cloud. As we advance it gradually resolves itself into fields of rugged rock, intermixed with stunted trees and at intervals large ruins of the same uniform black colour. This is the Lejah.

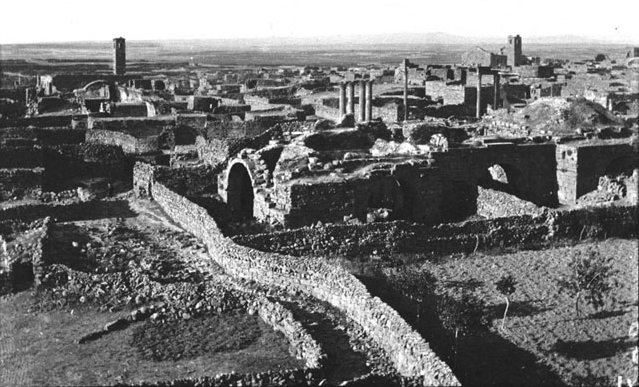

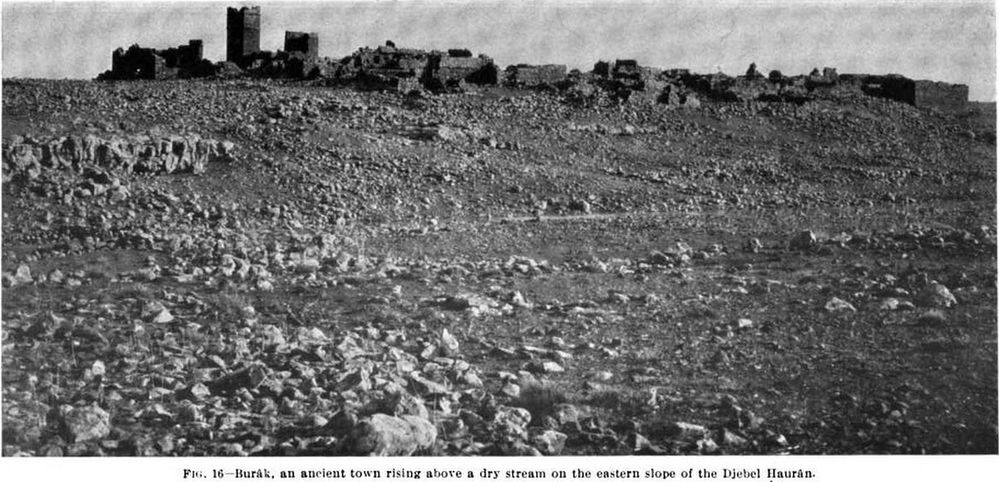

... 5 hours march from Nejha brings us to the town of Buråk on the north eastern corner of the Lejah. It is situated just within the wilderness of rocks and from its extent may at one time have contained 5000 or 6000 inhabitants ; but it is now and has been for centuries entirely deserted. This seems the more remarkable as many of the houses are perfect as the day they were built. We may go into one of them, stable our horses in one apartment, make a kitchen of another, a dining-room of a third, a bed-room of a fourth and then shut the doors and pass the night in peace. Such is the style of the domestic architecture of Buråk and indeed of all the towns and villages in the Haurán. Some of the houses are larger, some smaller, but the plan is the same in all—stone roofs, stone doors, some even have stone window shutters and in a few, where the chambers are large, a semicircular arch supports the roof. Thousands of them remain uninjured but tens of thousands are heaps of ruins. Their date it is impossible to fix. They may be of any age from Noah to Mohammed. One thing is evident, they were built during a period of prosperity and therefore before the Mohammedan conquest ...

(1) Auranitis (Hauran) -- Wikipedia

(2) Five years in Damascus: including an account of the history topography and antiquities of that city :

(3) Page 530 in A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: Part II by Josias Leslie Porter

(4) Page 394 in Cyclopaedia of Biblical Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature by John McClintock (1871)

(5) A Handbook for Travellers in Syria and Palestine: New and Revised Edition by Josias Leslie Porter

|