|

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online)

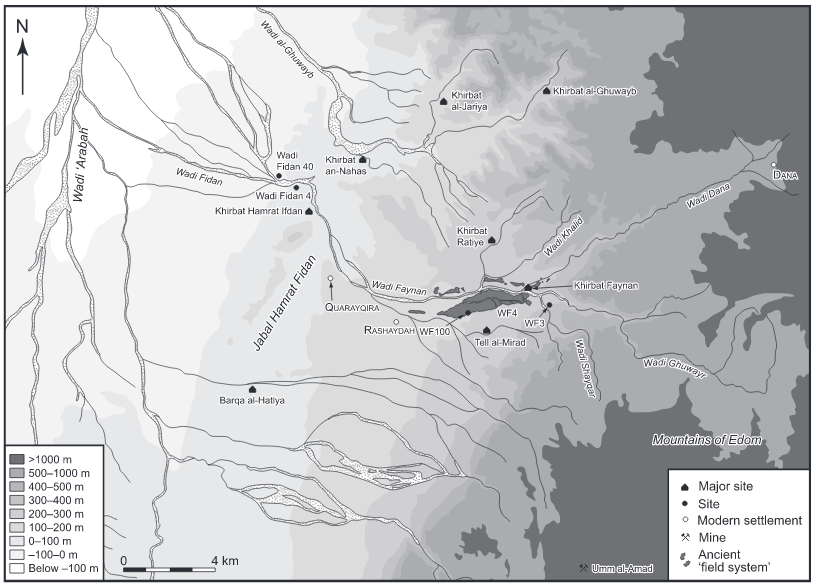

The PreHistoric Wadi Fidan Including Jabal or Jebel (Mount) Updated August 24th 2019 The “gateway” to the Faynan copper ore region from the west is through the Wadi Fidan which cuts through the Jabal Hamrat Fidan where Khirbat Hamra Ifdan (KHI) is situated. About 1 km to the north of KHI the Iron Age cemetery of Wadi Fidan 40 is situated (Page 759 in 1).

The Jabal Hamrat Fidan Project: Excavations at the Wadi Fidan 40 Cemetery in Jordan (1997) https://ancientneareast.tripod.com/PDF/The_Jabal_Hamrat_Fidan_Project_Excavatio.pdf Introduction  The Jabal (Arabic == Mountain) Hamrat Fidan in southern Jordan marks the gateway to the Wadi Faynan District; the largest source of copper ore in the southern Levantine mainland. Although

copper ore bodies are known from the Sinai and the western Arabah at Timna, the Faynan district was

the most significant source of copper ore for ancient

communities living in what is today Jordan -- Israel --

Palestine up until the end of the Early Bronze Age (circa 2000 BC). At this time the ore sources of Cyprus

began to take precedence and maritime trade in

copper established Cyprus as the most important

source of copper in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Jabal (Arabic == Mountain) Hamrat Fidan in southern Jordan marks the gateway to the Wadi Faynan District; the largest source of copper ore in the southern Levantine mainland. Although

copper ore bodies are known from the Sinai and the western Arabah at Timna, the Faynan district was

the most significant source of copper ore for ancient

communities living in what is today Jordan -- Israel --

Palestine up until the end of the Early Bronze Age (circa 2000 BC). At this time the ore sources of Cyprus

began to take precedence and maritime trade in

copper established Cyprus as the most important

source of copper in the eastern Mediterranean. Exploitation of Faynan copper ore spans the entire range of human occupation in the southern Levant with an apparent short hiatus during the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (1900-1200 BC) and the beginning of the Iron Age (1200-1000 BC). Evidence for the use of copper ore in the region is known particularly from the Neolithic (eighth to seventh millennia) -- Chalcolithic (circa 4500 - 3600 BC) -- Bronze Age (circa 3600 - 1900 BC) -- Iron Age II (circa 1000 - 586 BC) -- Roman (37 BC - 324 CE) and early Islamic (circa 638 - 1099 CE) periods (Hauptmann 1989). We date the Wadi Fidan 40 cemetery to the Iron Age. However it is difficult to link the cemetery population with confidence to Iron Age populations living on the Edomite plateau to the east. For that matter the cemetery cannot be tied with any certainty to the newly discovered group of Iron Age metallugical sites along the Wadi Fidan.

Dating The calibrated BC dates range from 1130-815 cal BC with an intercept of the radiocarbon age with the calibration curve at 925 cal BC. Thus, with 95% confidence, the Wadi Fidan 40 cemetery can be dated to the twelfth - ninth centuries BC ... The intercept of the radiocarbon age with the calibration curve at 925 cal BC is intriguing in the light of known evidence concerning the occupation of Edom in the Iron Age and especially of recent discoveries in the wider Faynan region.

The Iron Age of southern Jordan It is perhaps too early to comment on the overall extent of Iron Age occupation in the Faynan region at this time -- however the evidence that currently exists suggests that there was a fairly widespread occupation in this region prior to the formation of the 'Kingdom of Edom' in the seventh century BC. While archaeological evidence supports the crystallisation of the 'Kingdom of Edom' in the seventh century BC (see Bienkowski forthcoming; Herr 1997; LaBianca and Younkers 1998) this process was probably well underway several hundred years earlier. However the exact nature of Iron Age state formation and the extent to which it may have relied upon the exploitation of the copper resources at Faynan requires further investigation.

The nature of occupation in southern Jordan during the early Iron Age

We have finished with allowing the Shasu clansfolk

of Edom to pass the fort of Merneptah that is in

Succoth, to the pools of Pi-Atum of Merneptah that

are in Succoth, to keep them alive and to keep alive

their livestock ... (Gardiner 1937 Late-Egyptian Miscellanies -- Pages 76-77).

[Here again a divergence from the main subject but so very interesting] ...

PAPYRUS ANASTASI VI 51-61 by Hans Goedicke in Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur (1987) Pages 83-98

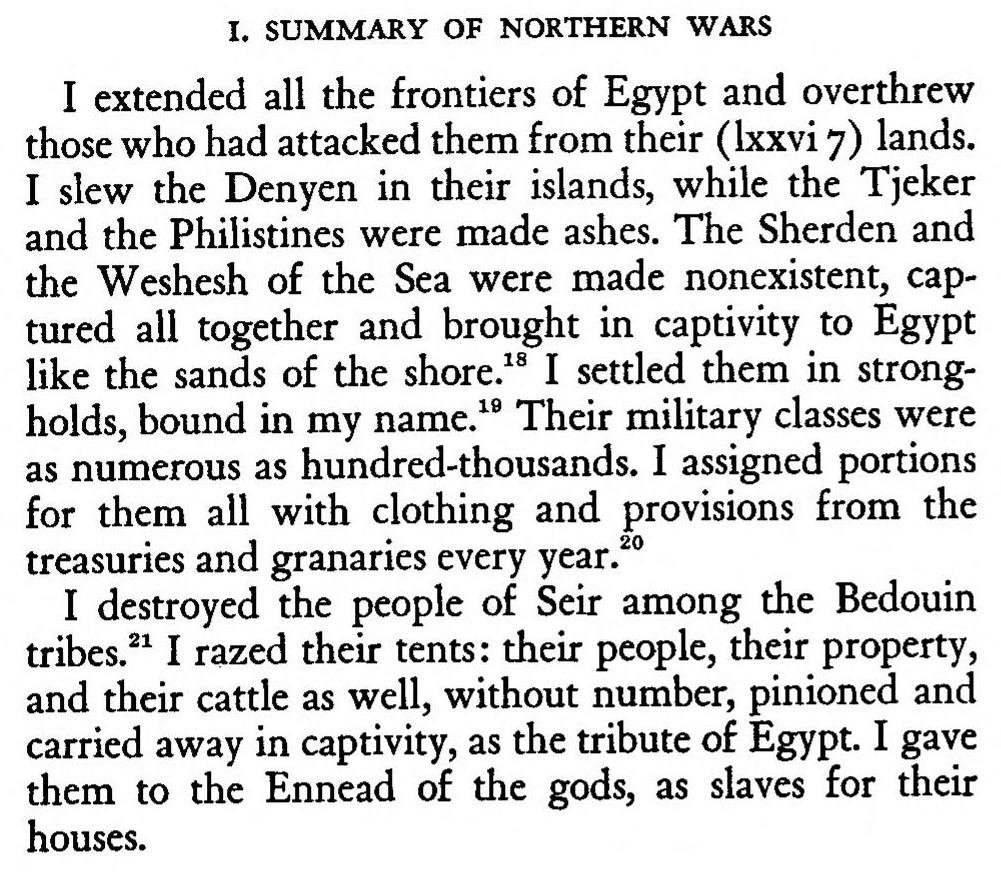

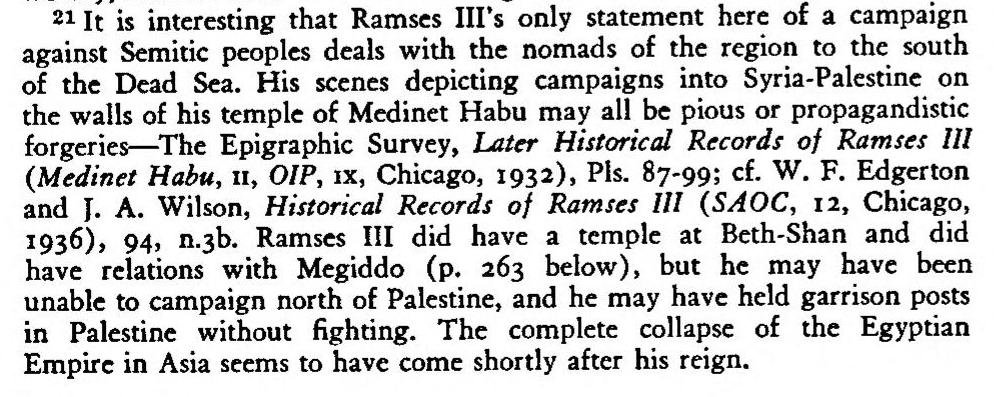

Other references including a piece of text from

the Papyrus Harris I from the reign of Rameses III (circa 1184-1153 BC) support this scenario of a population

whose economy was rooted in pastoralism.

I destroyed the Seirites, the clans of the Shasu; I pillaged their tents with their people, their property

and their livestock without limit ... (Pritchard 1969, 262:1)

Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating To The Old Testament Edited by James Pritchard (1969)

It is clear from these examples that the Egyptians

identified the inhabitants of Edom as Shasu -- a

problematic term but probably related to an

Egyptian word meaning 'wanderers' (Ward 1972,

56-59). The implication of this and other historical

data is that prior to the rise of what LaBianca and

Younker (1998) refer to as "Transjordan's tribal

kingdoms" in the post-ninth century BC, Edom was

most likely inhabited by pastoral non-sedentary

groups who lived in tents.

On the basis of this evidence it may be possible

to make some inferences about the nature of the

society buried in the Wadi Fidan 40 cemetery. The

circular character of the Wadi Fidan 40 tombs,

the absence of pottery and other indications of a

settled population may be indications that the individuals

interred in the cemetery were part of a

mobile pastoralist society. Although it may be premature

to tie the Wadi Fidan cemetery population

with certainty to any specific population group, it is

possible this population may be some of the first

archaeological evidence of the Shasu known from

the Egyptian historical records (cf comparison Ward 1972,

1992). How the Wadi Fidan 40 mortuary population

relates to other Iron Age sites in the Faynan

district and the wider southern Levant will be one

of the subjects of the Jabal Hamrat Fidan project in

the near future ...

The Southern Transjordan Edomite Plateau and the Dead Sea Rift Valley: The Bronze Age

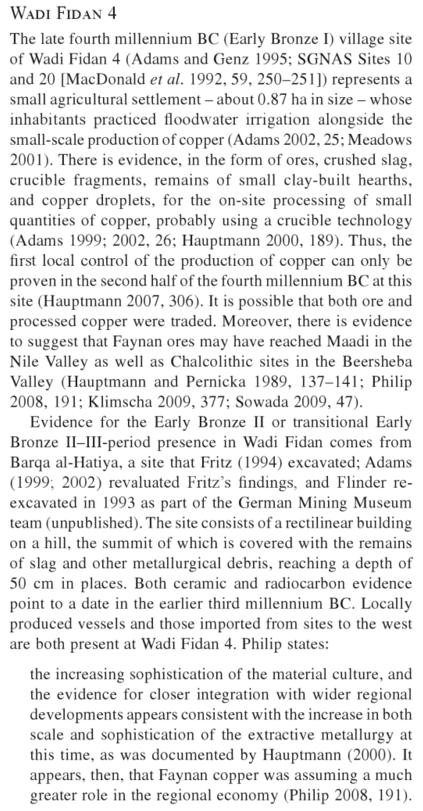

Wadi Fidan 4 Evidence for the Early Bronze II or transitional Early Bronze II-III period presence in Wadi Fidan comes from Barqa al-Hatiya, a site that Fritz (1994) excavated: Adams (1999, 2002) revaluated Fritz’s findings and Flinder reexcavated in 1993 as part of the German Mining Museum team (unpublished). The site consists of a rectilinear building on a hill, the summit of which is covered with the remains of slag and other metallurgical debris reaching a depth of 50 cm in places. Both ceramic and radiocarbon evidence point to a date in the earlier third millennium BC. Locally produced vessels and those imported from sites to the west are both present at Wadi Fidan 4. Philip states:

the increasing sophistication of the material culture and the evidence for closer integration with wider regional developments appears consistent with the increase in both scale and sophistication of the extractive metallurgy at this time as was documented by Hauptmann (2000). It appears then that Faynan copper was assuming a much greater role in the regional economy (Philip 2008, 191)

The Southern Transjordan Edomite Plateau and the Dead Sea Rift Valley: The Bronze Age

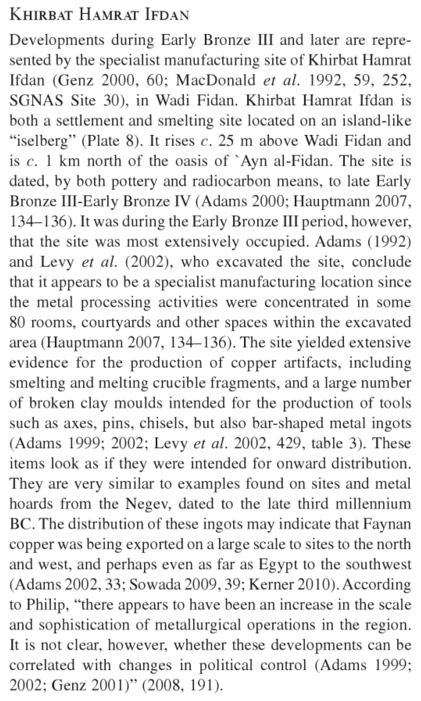

Khirbat Hamrat Ifdan

(1) New Insights into the Iron Age Archaeology of Edom in Southern Jordan by Erez Ben-Yosef -- Thomas Levy -- Mohammad Najjar (2014) |