|

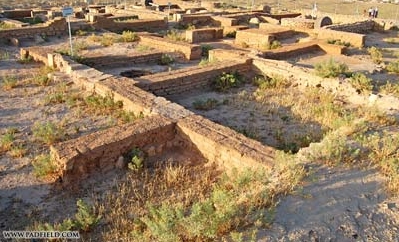

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) Ancient Haran or Harran (Assyrian Harranu) [Roman Carrhae] City of Mesopotamia Now in SouthEast Turkey Harran in antiquity was in the middle of a flat dry plain that was described as a barren wasteland nourished only by its many wells. The city of Harran was founded circa 2000 BC as a merchant outpost of Ur situated on the major trade route across northern Mesopotamia. The name comes from the Sumerian and Akkadian Harran-U meaning journey - caravan - crossroad. For centuries it was a prominent Assyrian city known for its Temple of the Babylonian Moon God Sin. Abraham migrated from his birth place in Ur to Harran (Genesis 11:31). It was the city of Nahor in the Bible (Genesis 24:10) -- Nahor being the brother of Abraham -- where their father Terah died, whereupon Abraham migrated to Canaan. Harran was an important commercial city and is mentioned in Assyrian business documents from Cappadocia. The town, like all the other cities of that region, probably had a large Jewish community up to the Middle Ages. In the Christian and early Moslem Period Harran was one of the last strongholds of Babylonian paganism (1) In the 6th century BC after the fall of Nabonidus in Babylon, Harran was ruled by the Persians until the coming of Alexander the Great in the 4th century BC. After him Harran was part of the Hellenistic Seleucid Kingdom until the 2nd century BC when the Parthians conquered the Seleucids. In the 1st century BC the Romans arrived. During this time Harran passed through many hands and was usually at least nominally under foreign authority but in practice independent ... (2) The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran By Tamara M. Green (1992)

CHAPTER ONE

Harran’s continuing role as a trading city along the mercantile routes of northern Mesopotamia in the first millennium B.C.E. is attested to by the prophet Ezekiel who includes Harran among the cities that trafficked in luxury goods: “Haran, Canneh, Eden, Ashur and Chilmad traded with you. These traded with you in choice garments, in cloths of blue and embroidered work and in carpets of colored stuff, bound with cords and made secure”. And later references by Roman authors such as Pliny indicate that Harran maintained an important position in the economic life of Northern Mesopotamia throughout the classical period. The city was a major post along the trade route between the Mediterranean and the plains of the middle Tigris for it lay directly on the road from Antioch eastward to Nisibis and Nineveh whence the Tigris could be followed down to the delta to Babylon. There was another route, a much shorter one, from Antioch to Babylon: down the Euphrates through Carchemish, Anah and Hit. From there (Harran) two different royal highways lead to Persia: the one on the left through Adiabene and over the Tigris; the one on the right through Assyria and across the Euphrates. Harran’s importance was that not only did it lay directly on the first path, the Assyrian road, but had easy access to the second or Babylonian road. Harran was on the road north to the Euphrates as well and thus provided an easy access to Malatiyah and Asia Minor. Harran seems to have had a special political and military relationship to the Assyrian kings, who had recognized its strategic importance. The annals of the Assyrian King Adad-Nirari I (circa 1307-1275 B.C.E.) report that he conquered the “fortress of Kharani” and annexed it as a province. Not only does it appear in the inscriptions of Tiglath-Pileser I (1115-1077 B.C.E.), who was pleased with the abundance of elephants in the region for hunting and who had a fortress there, but a 10th century inscription reveals that Harran shared with Ashur the privilege of certain types of fiscal exemption and freedom from some forms of military obligation. The city’s status is further attested to by the fact that in the ninth and eighth centuries B.C.E. its commander was the tartan -- the highest military commander of the Assyrian empire -- and held the title of limmu, the eponym of the year next in sequence after the king himself. Even its transgressions seem to have been lightly punished for it is recorded that Sargon (721-705 B.C.E.) restored the privileges of the “free city of Harran” which had been lost at the time of rebellion. The political prominence of Harran in the Assyrian period was due in large measure to its protecting deity Sin; (1)the god of the Moon and giver of oracles and (2)the guardian of treaties whose eye sees and knows all; and [also] the temple of the Moon god, called Ehulhul (Sumerian: “Temple of Rejoicing”) at Harran [which] was restored several times during the first millennium B.C.E., sometimes as an act of political piety and sometimes as an act of personal devotion to the god ...

(1) The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia Edited by Isaac Landman (1940)

(2) The City of the Moon God: Religious Traditions of Harran By Tamara M. Green (1992)

See Also: Harran © 1995–2017 Livius.org

|