|

Other Archaeological Sites / The Neolithic of the Levant (500 Page Book Online) Ancient Canaanite and Israelite City-State Hazor (Arabic Tell Qedah) in Israel

Hazor in Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books Hazor in the Encyclopaedia Judaica by Yigael Yadin and Shimon Gibson

The prominent mound of Tell el-Qedah (also called Tell Waqqas), the Arabic assignation of Hazor, was first identified with biblical Hazor by Josias Leslie Porter (9) in 1875 on the basis of geographic references in 1 Maccabees 11:67 and Josephus Antiquities of the Jews 5.199 (Page 560 in 7).

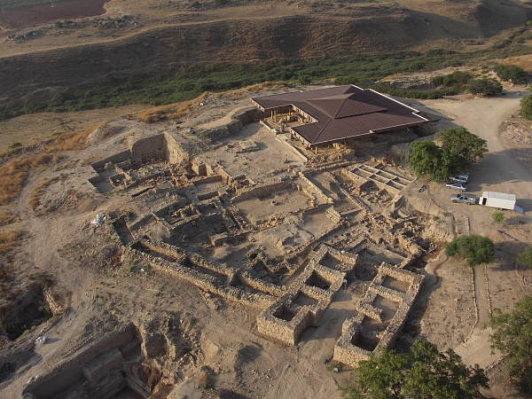

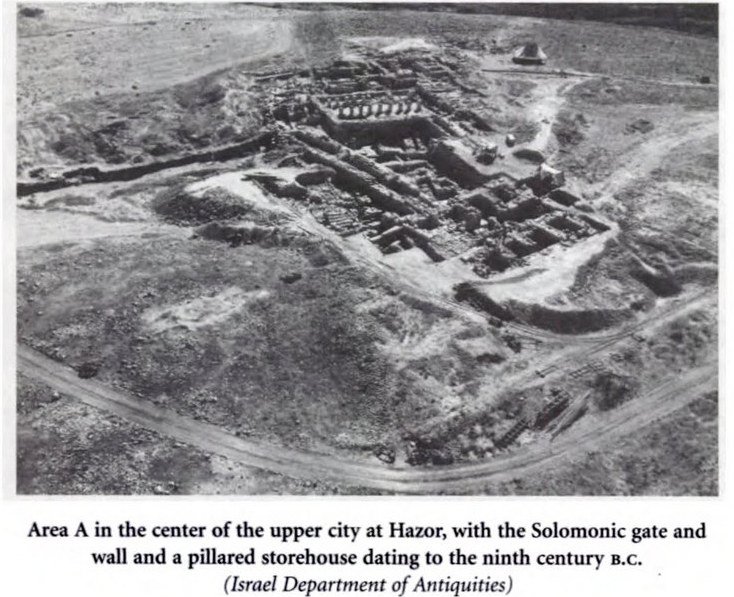

In 1928 the British archaeologist John Garstang conducted a limited or preliminary excavation at the site. Large-scale excavations were conducted during 1955-58 and 1968-69 by a team led by the late Yigael Yadin. These excavations were conducted on behalf of the Hebrew University. Renewed excavations have been conducted since 1990 by the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, the Complutense University of Madrid and the Israel Exploration Society (Publications). Amnon Ben-Tor has led the Hazor excavations since 1990 to the present (Twenty-ninth Season -- Summer 2018). It has been declared by UNESCO a World Heritage Site. Hazor is the largest biblical-era site in Israel and covers some 200 acres (1) comprising two parts --- a tell or upper city (acropolis) that covers thirty acres and a large rectangular plateau or lower city on the north side of the tell that encompasses 175 acres. The bottle-shaped upper city rises 120 feet above the surrounding plain while the lower city attains a height of sixty feet above the surrounding wadis and plain. In ancient times the lower city was fortified by a large earthen rampart with a glacis (plastered slope) and a moat (10). The population of Hazor in the second millennium BC is estimated to have [ranged upwards from] 20,000 (Page 203 in 11) --- making it the largest and most important city in the entire region. Its size and strategic location on the international trade route connecting Egypt and Arabia to Mesopotamia (Babylonia) -- Syria -- Anatolia made it the head of all those kingdoms (Joshua 11:10) (1) (10). The site’s location at the meeting point of the main road from Sidon to Beth-shean with that from Damascus to Megiddo (Via Maris) renders it the most strategically important site for controlling northern Palestine (7).

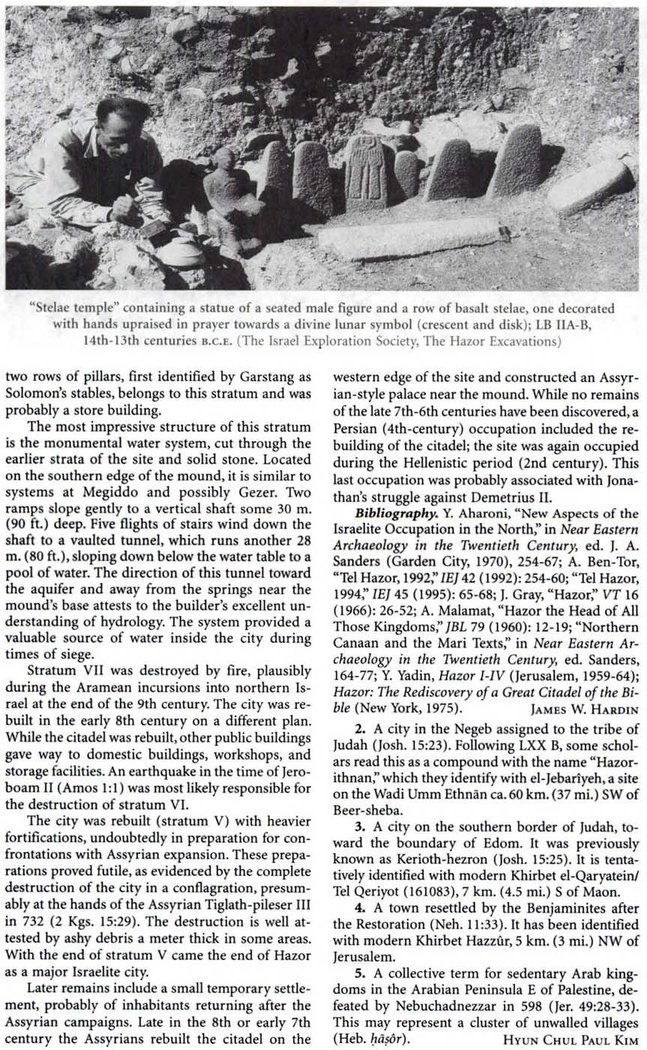

Excavations over the decades have revealed 21 strata (I-XXI) of occupational debris on the upper tell (8) extending from sometime in the Early Bronze II (2900-2600 B.C.) (10) to the Hellenistic period (second century B.C.) (7) (16). The earliest habitation of the site took place on the tell or upper city itself. During the Middle Bronze Age the lower city was first settled in the 17th century B.C.E. and was totally abandoned by the Late Bronze Age in the 13th century B.C.E. (strata 4 3 2 1B 1A) (15). With the fortification of the vast enclosure of the lower city Hazor became the largest Canaanite city-state in Palestine. (10). The Canaanite city of the Middle Bronze Age is characterised by monumental architectural features that betray the northern influences from the Syro-Mesopotamian cultural sphere. The most prominent of these were the massive rampart and moat surrounding the lower city, particularly in the west and north, and two city gates. However it is the number and variety of temples that most emphatically indicate the cosmopolitan character of the city. Their different designs and features suggest that a variety of ethnic and religious traditions existed side-by-side at Hazor throughout the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (20).

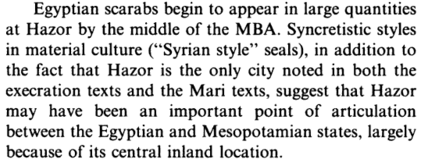

Late Bronze Age (circa 1550-1200 BCE) (20) At least eight cuneiform tablets have been found at Hazor dating to the Middle and Late Bronze Ages (2000-1200), mostly administrative and legal. One is a Sumer-Akkadian dictionary, suggesting the presence of a scribal school at Hazor (7). Textual References: The earliest reference to Hazor appears in the 19th century Egyptian Execration Texts (7). Dating to the time of the Twelfth Dynasty (the period of the Middle Kingdom in Egypt) these texts contain the names of vassal city-states in Syria-Palestine (10) who were enemies of the Egyptian state or troublesome foreign neighbors (B).

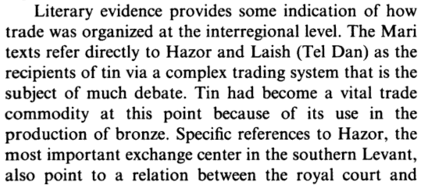

It is next mentioned in at least 14 documents from the 17th-century archives of Mari (7). The tablets indicate that the city was an active caravan center, a major governmental center involved in diplomatic activities with Mesopotamia and a center of metal trade (tin) (17) (10).

Hazor is mentioned in four of the Amarna Letters (14th century) (7). Letters from neighboring city-state kings include complaints that Abdi-Tarshi (city-state king of Hazor) had rebelled against the Egyptian pharaoh, had captured several cities from neighboring city-states and added them to his own territory, and had aligned himself with the Habiru [possibly the Hebrew people] (10).

Hazor’s location on the international trade route and its strategic position in northern Palestine made it a prime target for the imperialistic pharaohs of Egypt. Hazor appears in the lists of cities captured in the annals of Egyptian New Kingdom (1550-1070 B.C.) pharaohs of the Eighteenth and Nineteenth dynasties including Thutmose III -- Amenhotep II -- and Seti I (7) (10). Hazor also appears in the 13th-century Papyrus Anastasi I ascribed to Rameses II (7). One of the earliest biblical references to Hazor involves Jabin, the king of Hazor, who called together kings from various locations in northern Canaan to meet the threat of the Israelites under Joshua (Joshua 11:1-5) (7). Hazor's conquest by Joshua opened the way for the Israeli conquest and settlement of Canaan (1). At a later time the Jabin Dynasty appears to have recovered power and restored the city (Judges 4:2). The heavy defeat of their army at the hands of Deborah and Barak led to their final downfall (Judges 4:23) (21). Hazor was then assigned to the tribe of Naphtali (Joshua 19:32-6) (7).

Archaeology: Near the end of the Late Bronze Age Hazor experienced massive destruction, perhaps by Joshua and the Israelites (Joshua 11:1-13) and the lower city was never again occupied (10). Ben-Tor stops short of naming Joshua, preferring to cite the "Israel" of the Merneptah Stele as the most likely candidate for the violent destruction of Canaanite Hazor (Page 179 in 25). The date of the destruction of the Bronze Age city is still a matter of dispute; however both Yadin and Ben-Tor place this destruction in the latter part of the 13th century B.C. (16) ... Ben-Tor [though] cautions that the pottery from the destruction can be dated to any stage in the thirteenth or even late in the fourteenth century BCE. However the preponderance of evidence points to a thirteenth-century date for the destruction and Ben-Tor agrees that the most likely perpetrators were the early Israelites, who settled in the central hill country of Canaan shortly afterward and who were mentioned in the Merneptah Stele in the late thirteenth century BCE (20). Page 90 in Davies (2008): "Assuming we have Merneptah's dates correctly as 1213-1203 B.C. and that the reading "Israel" is correct, the reference places an Israel in Palestine in the thirteenth century. The word read (probably correctly) as "Israel" also has a sign indicating a people and not a place. That makes the alternative reading Jezreel (city) [or the valley --- Greek word Esdraelon] less likely" ... Two layers of Israelite occupation at Hazor in the Iron Age I period between the destruction of the Canaanite city and the rebuilding of the city by Solomon show merely semi-nomadic Israelite encampments evidenced by tent or hut foundation rings -- cooking pits -- storage pits and two small cultic installations. This early Israelite settlement was limited to the area of the upper city or tell (10) (16). The meager Israelite occupation in the 12th and 11th century BC was replaced by a well fortified city during the Solomonic era (22).

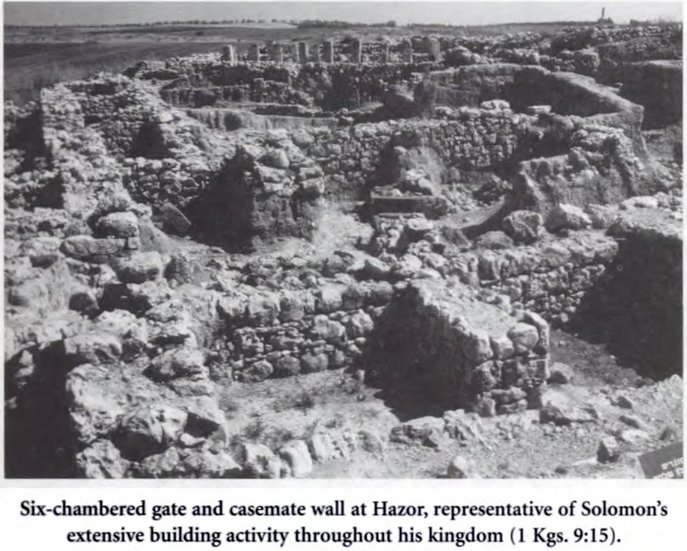

During the latter part of the Iron Age I period (tenth century BCE) the upper city was buttressed with a casemate wall and a chambered gateway with flanking towers. As an Israelite city Hazor was established as a fortified garrison and major royal administrative center by Solomon during the united monarchy (level X) (1 Kings 9:15). Solomon built similar fortifications at Megiddo and Gezer (10).

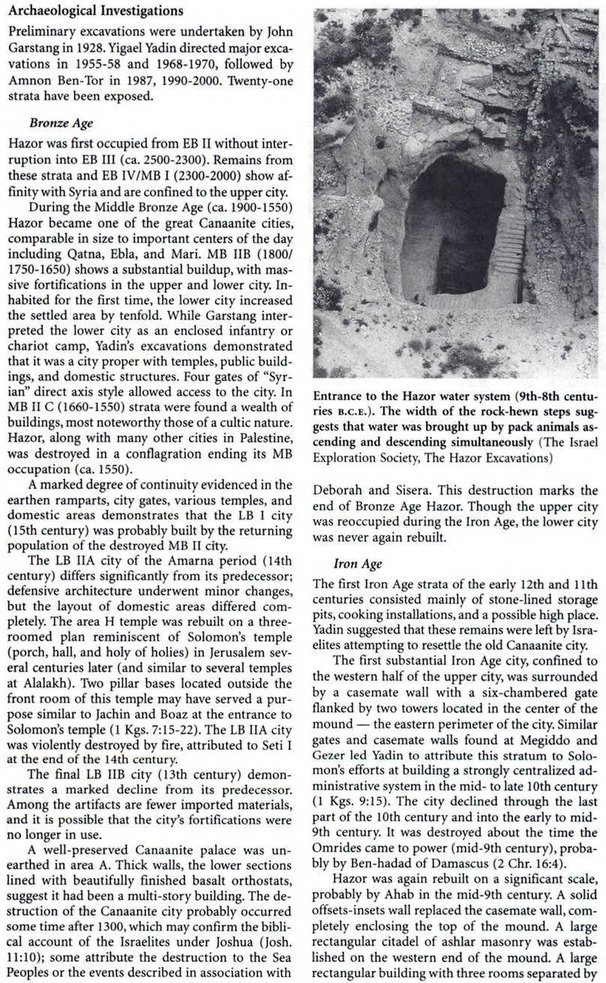

Israel Finkelstein [in Hazor and the North in the Iron Age: A Low Chronology Perspective] has sought to ascribe level X to a later period, partly due to his attempts to lower the traditionally accepted dates of Iron Age levels by up to a century. Ben-Tor rejects Finkelstein’s arguments and continues to assign stratum X to the tenth century on the basis of the ceramic record rather than the biblical account (20 Section 6.1 and 24). Yadin specifically names Ben-Hadad I as a candidate for the destruction of Stratum IX (Yadin 1972: 200) (24). The Solomonic city of Hazor, inherited by the northern kingdom of Israel following the division of Solomon's kingdom, came to a fiery end (in the early 9th century BCE) when Ben-Hadad I of Damascus invaded Israel at the request of King Asa of Judah. Later in the same century it was rebuilt by Ahab (12). 1 Kings 15:20: (KJV) So Benhadad hearkened unto king Asa, and sent the captains of the hosts which he had against the cities of Israel, and smote Ijon, and Dan, and Abelbethmaachah, and all Cinneroth, with all the land of Naphtali ... The successive Stratum VIII in the Iron Age II dates to the Omride Dynasty, to the time of Ahab (reigned circa 871-852 BC). The city had doubled in area, now occupying the whole upper mound and was surrounded by a solid wall (23). Under King Ahab there was added a large storehouse and a fortified citadel as well as the elaborate water system constructed in the upper city. The water system is comprised of a huge upper shaft with a rock-cut staircase, a sloping tunnel and a pool room in which the water supply was located. (10). "There is thus reason to attribute the destruction of Stratum VII to the Aramean invasion of Hasael [sic] King of Damascus . . . about 815 B.C." (Hazor I: an Account of the First Season of Excavations by Yadin et al 1958: 23) (24). It seems that Hazor was destroyed during wars with the Arameans in the 9th century BC (23). Archeologists Yigael Yadin and Israel Finkelstein date the earthquake level at Tel Hazor to 760 BC based on stratigraphic analysis of the destruction debris (C). Stratum VI, dating to the reign of Jeroboam II, was probably destroyed by earthquake (see Amos 1:1 and Zechariah 14:5). Stratum VB is dated to the reign of Menachem. In the successive Stratum VA the fortifications were broadened on the eve of Tiglath Pileser III's invasion in 732 BC (Second Book of Kings 15:29) (23). With its final destruction by the Assyrians (2 Kings 15:29) in 732 BC its population was deported and the city was burnt to the ground (1). Following this destruction by the Assyrians Hazor was never again occupied as a city. The final phases of Hazor’s history date to the Assyrian -- Persian -- and Hellenistic periods from which evidence of fortresses have been found (10) until the time of the Maccabees (167 BC) (16).

1 Maccabees 11:67: Meanwhile Jonathan and his army pitched their camp near the waters of Gennesaret,

(5) Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis, Israelite City by Amnon Ben-Tor (2016)

(4) Hazor "The Head of All Those Kingdoms" by A. Malamat (Hebrew University) In the description of Hazor in the Book of Joshua these evocative words are added incidentally: “For Hazor beforetime was the head of all those kingdoms" -- words that bear witness to the greatness of the city before the Israelite conquest. According to scriptural tradition the king of Hazor was at that time the head of a broad alliance of Canaanite kings in the north of the country while inscriptions from the 2nd millennium B. C. also attest Hazor's importance as a political center. The city is mentioned for the first time in the Egyptian Execration Texts of the 19th century (4). Hazor is the only Canaanite site mentioned in the archive discovered in Mari (18th century BCE). The Mari documents clearly demonstrate the importance, wealth and far-reaching commercial ties of Hazor. In the archive discovered at Amarna Egypt (14th century BCE) there are several references to Hazor as an important kingdom in northern Palestine which exercises a dominant influence over a wide area. There are also records of the military campaigns conducted by the Egyptian Pharaohs during the 15th-14th centuries (1).

(3) Page 108-9 in Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature:

But by the time of Deborah and Barak the Canaanites had recovered part of the territory then lost, had rebuilt Hazor, and were ruled by a king with the ancient royal name of Jabin [dynastic name], under whose power the Israelites were in punishment for their sins and reduced. From this yoke they were delivered by Deborah and Barak, after which Hazor remained in quiet possession of the Israelites and belonged to the tribe of Naphtali. Solomon did not overlook so important a post and the fortification of (1) Hazor -- Megiddo and Gezer, the points of defence for the entrance from Syria and Assyria, (2) the plain of Esdraelon and (3) the great maritime lowland respectively, was one of the chief pretexts for his levy of taxes. Later still it is mentioned in the list of the towns and districts whose inhabitants were carried off to Assyria by Tiglath-Pileser III. Hatzor never regained its past glory; only a small settlement continued to exist there, until that too was abandoned in the Hellenistic period (2).

(6) Dictionary of the Ancient Near East edited by Piotr Bienkowski and Alan Ralph Millard Hazor: Tell el-Qedah -- a site in Palestine 14 km north of the Sea of Galilee -- was identified by Josias Leslie Porter in 1875 with biblical Hazor. Hazor is first mentioned in the Execration Texts and in documents from Mari which show that it was involved in the tin trade with Babylonia. It appears in Egyptian lists of conquered cities in the Late Bronze Age and in the Amarna Letters, where its king is accused of joining the habiru. In the Old Testament Hazor is an important Canaanite city destroyed by the invading Israelites; it was later rebuilt by Solomon and conquered by Tiglath-pileser III. Hazor consists of an upper city on the 12 hectare mound occupied from the Early Bronze Age to the Hellenistic period and a large lower city of 70 hectares occupied only in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages. The lower city was once regarded as an enclosure or camp for infantry and chariotry but it is now certain that it was a fortified built-up area. Hazor was the largest city in Canaan in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages with a population estimated at twenty thousand. The massive defences, erected in the Middle Bronze Age and perhaps re-used, enclosed a palace, domestic structures, temples and tombs; several cuneiform tablets, one noting the arrival at Mari of livestock from Hazor and an inscribed liver model reflect Hazor’s Babylonian connection. The Late Bronze Age city suffered a massive destruction with statues deliberately smashed. Several lron Age strata show the development of the fortified lsraelite city with its citadel including a Solomonic six-chamber gateway, residential quarters, workshops and stores. A water system consisted of a shaft cut through rock leading to an underground spring. After a destruction attributed to Tiglath-pileser III (734 BC) a series of citadels was constructed until the Hellenistic period, after which the site was abandoned. (7) Pages 560-2 in Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible Edited by David Noel Freedman (2000)

The name "Hazor" may mean "enclosure" or "settlement" and was

(1) The Selz Foundation Hazor Excavations in Memory of Yigael Yadin: The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (2) Hatzor: "The Head of all those Kingdoms" --- The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs

(3) Page 108-9 in Cyclopaedia of Biblical, Theological and Ecclesiastical Literature:

(4) Hazor "The Head of All Those Kingdoms" by Abraham Malamat (Hebrew University) (5) Hazor: Canaanite Metropolis, Israelite City by Amnon Ben-Tor (2016) (6) Dictionary of the Ancient Near East edited by Piotr Bienkowski and Alan Ralph Millard --- University of Pennsylvania Press (2000) (7) Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible Edited by David Noel Freedman (2000) (8) Tel Hazor by Shlomit Bechar at the Biblical Archaeology Society (9) Jerusalem, Bethany and Bethlehem by Josias Leslie Porter (1886) (10) Cities of the Biblical World: An Introduction to the Archaeology, Geography and History of Biblical Sites by LaMoine DeVries (2006) (11) The World and the Word: An Introduction to the Old Testament by Eugene Merrill -- Mark Rooker -- Michael Grisanti (2011) (12) Hazor at BIBARCH™ (Biblical Archaeology) (13) Domination and Resistance: Egyptian Military Activity in the Southern Levant Circa 1300-1185 B.C. by Michael Hasel --- BRILL (1998) (14) Old Testament Survey: The Message, Form and Background of the Old Testament by William Sanford LaSor -- David Allan Hubbard -- Frederic William Bush -- Leslie C. Allen (1996) (15) Area S: Renewed Excavations in the Lower City of Hazor by Sharon Zuckerman in Near Eastern Archaeology (June 2013) (16) Holman Illustrated Bible Dictionary Edited by Chad Brand, Eric Mitchell, Holman Reference Editorial Staff (2015) (17) Trade and Cultural Exchange at Hazor by Kristina Hesse ©Copyright 2017 Society of Biblical Literature (18) Encyclopedia of Prehistory --- Volume 8: South and Southwest Asia edited by Peter Peregrine and Melvin Ember (2003) (19) Israel's History and the History of Israel By Mario Liverani --- Routledge (2014) (20) Dictionary of the Old Testament: Historical Books edited by Bill T. Arnold and H. G. M. Williamson (2011) (21) Hazor in © 2004 - 2017 Bible Hub (22) Tyndale Bible Dictionary by Walter A. Elwell and Philip Wesley Comfort (2001) (23) The Fortifications of Ancient Israel and Judah 1200–586 BC by Samuel Rocca (2012) (24) Hazor and the Chronology of Northern Israel: A Reply to Israel Finkelstein by Amnon Ben-Tor in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research Pages 9-15 (2000) (25) A Biblical History of Israel by Iain Provan -- V. Philips Long -- Tremper Longman III (2003) (26) Pharaohs of the Bible (Mizraim to Shishak): A Unifying High Chronology of Egypt Based on a High View of Scripture by Eve Clarity (2012) (A) Tel Hazor --- WikiPedia (B) Execration texts --- WikiPedia (C) Jeroboam II --- WikiPedia

Page 192 in 14 |